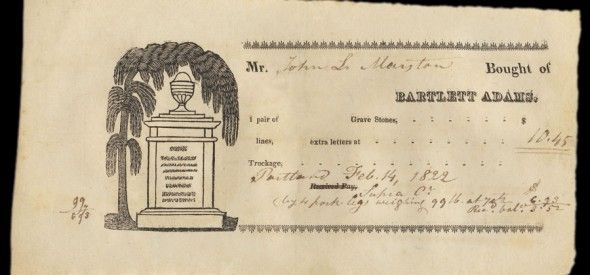

I recently won a steel engraving proof on eBay, one of the thousands of engraving proofs that have been out there for several years now following the sell-off of the archives of the American Bank Note Company (ABN). A premier securities printer since the mid-1800s (including the printing of many classic US postage stamps), the mid-1900s owners of the firm attempted to profitably market some of the spectacular examples of steel engraved masterpieces held in the archive configured into various modern “collectible” products, over several years, to no avail. Wonderful as the material was (and is), they could come up with no way to sell these old engravings in new formats to contemporary buyers. The world, it seems, had moved on. And so the material was put on the auction block in a series of sales and scattered to the four winds. Bits and pieces of it still pop up on eBay, on other online sites, in stamp and ephemera dealer stocks and in all sorts of other odd places.

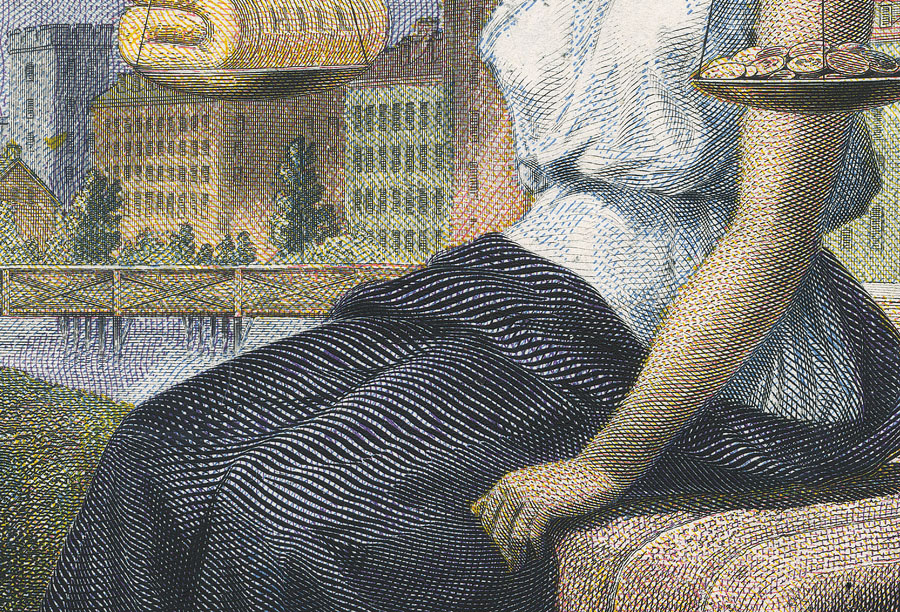

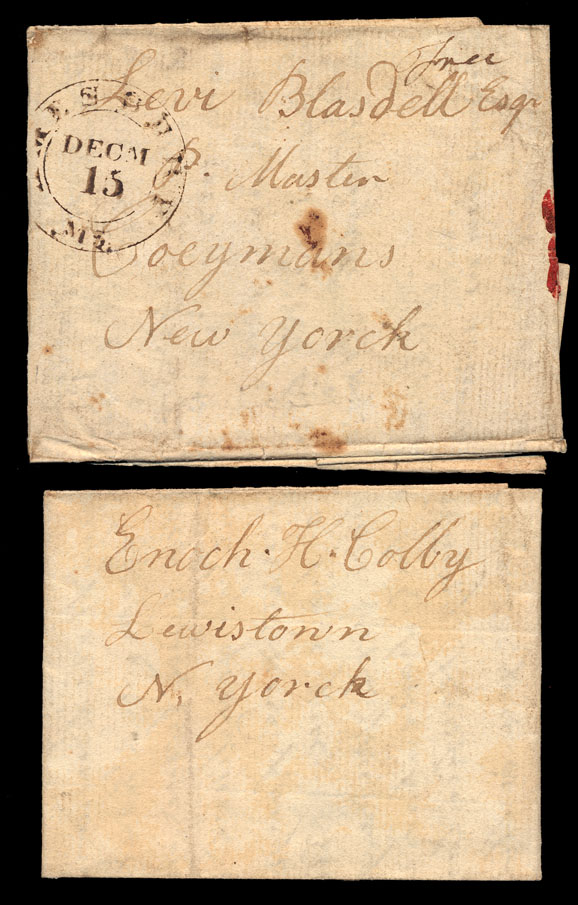

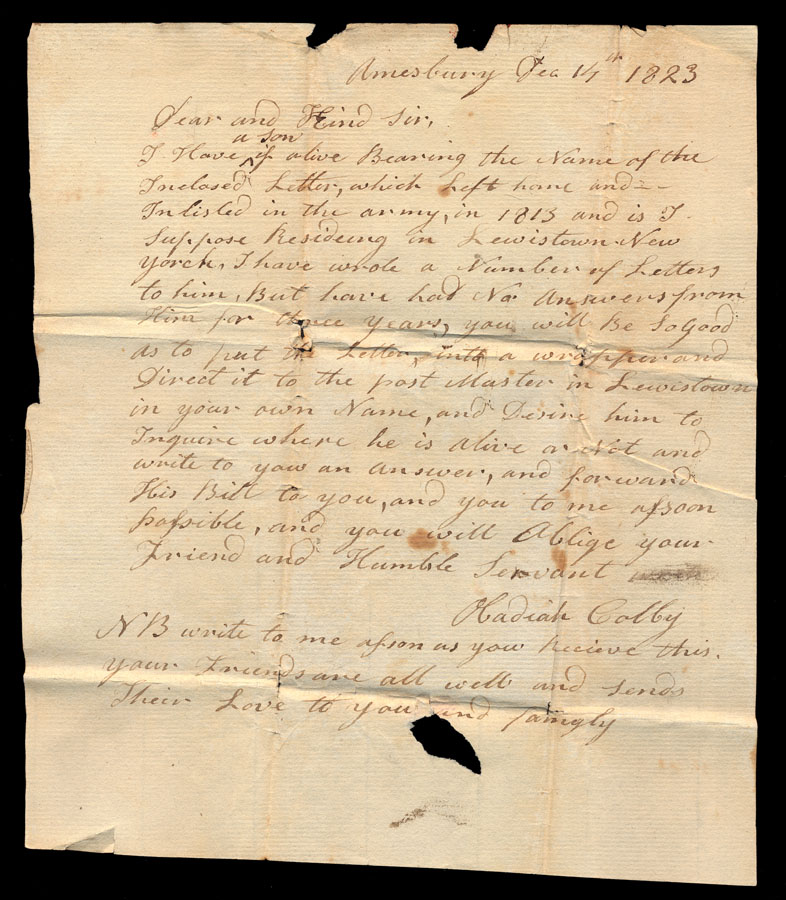

So I bought one of these items, listed by a frequent seller of such ABN remnants as “Art Work” from the archive. From the somewhat unclear image, I could not tell if it was perhaps original artwork, a painting created to guide the engravers (which was unlikely) or a black and white steel engraving which had been later “colorized” with washes of watercolor (which was more likely). In any case, it was an attractive, large (4? x 6? image area) vignette, a woman sitting on bales of cotton holding a balance scale with a bolt of cloth on one side and gold coins on the other; for the modest selling price, it seemed well worth having.

When I received the item, I discovered it to be a highly unusual example of a rarely used security printing process. I had never seen an example. It is not original reference art, but neither is the color in the piece the result of any wash of paint; rather, each of the many colors was individually printed in register by ABN, line by line. Throughout, colors overprint other colors, which required multiple passes. I have begun looking into the process, which I still do not fully understand, primarily because details of the proprietary process have been a closely-held company secret. But I have begun to learn some things.

I spoke with Ephemera Society member and security engraving expert Mark Tomasko, and subsequently slipped his excellent book The Feel of Steel (2009 by Bird and Bull Press, and 2012 by The American Numismatic Society) from my library shelf.

Mark shares the information that this highly unusual ABN printing process was referred to as “Major Tint”, developed by ABN in the 1920s, named after two employees (Alfred S. Major and his brother Walter Major). It was used almost exclusively on foreign banknotes (mostly in Latin America) rather than on security documents such as stock shares.

Going back to my library shelves, I find that in the 1959 book The Story of The American Bank Note Company, the official company history by William H. Griffiths, the “Major Tint” process is discussed in general terms:

“This process has remained unique . . . although . . . there have been numerous attempts throughout the printing industry to perfect similar systems.” “Since the process is not in general use, there does not exist any common name for it. It is a form of surface printing, using an intermediary cylinder as in offset lithography, but in other features, it differs materially from that process. The work it produces exhibits distinctive characteristics: first, a large number of different colors may be used; second, the registration of the various colors is precise beyond all comparison; third, the quality of printing is uniform over long runs.” ” . . . when a Major Tint is combined with fine engraving, [a] counterfeiter is given a frustrating problem, no matter what lenses and filters he possesses. For in the Major Tint there may be colors that are so nearly alike or so intermingled that filters cannot separate them. Lines may cross so cleanly that a camera film cannot reproduce the sharpness of the junction. The color of a line may change gradually along its length. Finally, the color or shade of a line may change across its breadth, because the virtually perfect registration of the press makes it possible to print a hairline over one side of a slightly wider line.”

My example, which seems clearly to be an earlier 19th-century piece of work (ABN die #V44820) which was used to explore the new process, was carefully printed on a proof press. Most areas done in black (skirt, hair, facial details) were indeed steel engraved. Virtually all the rest of the image, however, in at least five colors (blue, yellow, red, purple, black) are not steel engraved. They were printed by what Mark describes as “offset letterpress”, in close registration. Other sources have labeled the process “indirect low relief” printing. Individually, of course, offset and letterpress are two distinctly different processes. Offset printing is “planographic” (flat) printing, in which an image is offset onto a (often rubber) blanket from a plate, then onto the paper. Letterpress is generally printed from type/images standing tall at “type high”, inked, then pressed into the paper. I am still trying to piece together the details of this hybrid “offset letterpress”, but it seems that perhaps letterpress elements were first offset onto a blanket and then onto the paper. There was also a printing process used elsewhere dubbed “indirect letterpress” where the letterpress elements were pressed into the back of the paper rather than onto the front. Perhaps this is relevant here. Or not.

ABN went as far as developing a new printing press capable of doing this sort of printing on a commercial scale, though how much it was actually used is unclear. ABN log pages show occasional “Major Tint” notations on foreign banknote production from the 1920s through the 1950s.

In any event, a very interesting and unusual process.

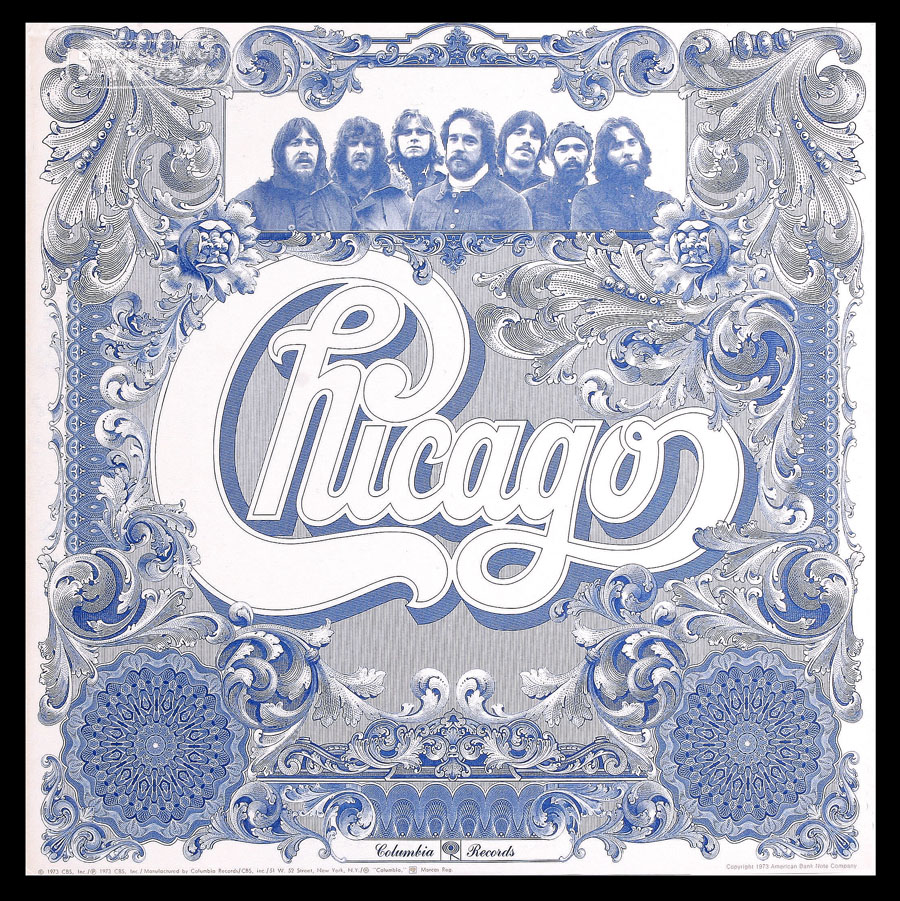

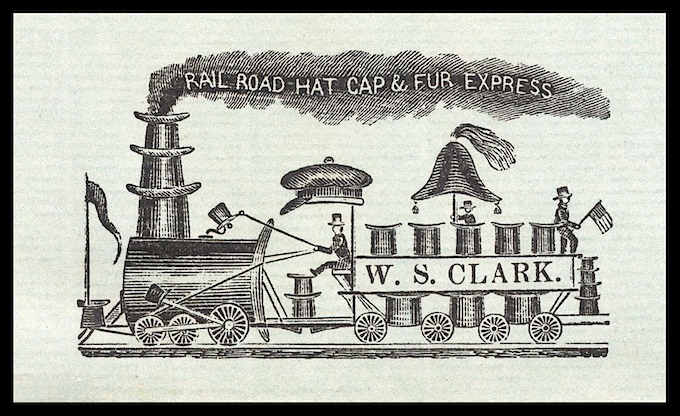

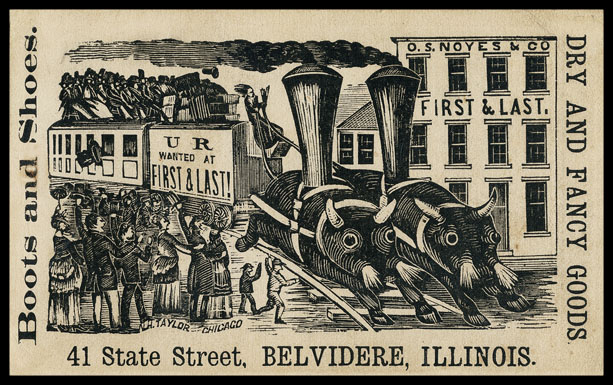

While on the subjects of steel engraving, American Bank Note and the unusual, check out this vinyl record album cover for the jazz / pop /rock band CHICAGO. On this 1973 album, CHICAGO’s fifth, the front cover is totally steel engraved! Unusual, to say the least. It was done by ABN using various 19th-century elements from its archive . . . acathus leaves, Rose engine lathework, border elements, etc. ABN also did the inner album sleeve (offset printed) and included on it a vignette of a 1850s train, previously only known in partial form on a Fourth Issue United States 10¢ Fractional note (paper currency used during the Civil War when metal coins became in short supply; used only between August 21,1862 and February 15, 1876).