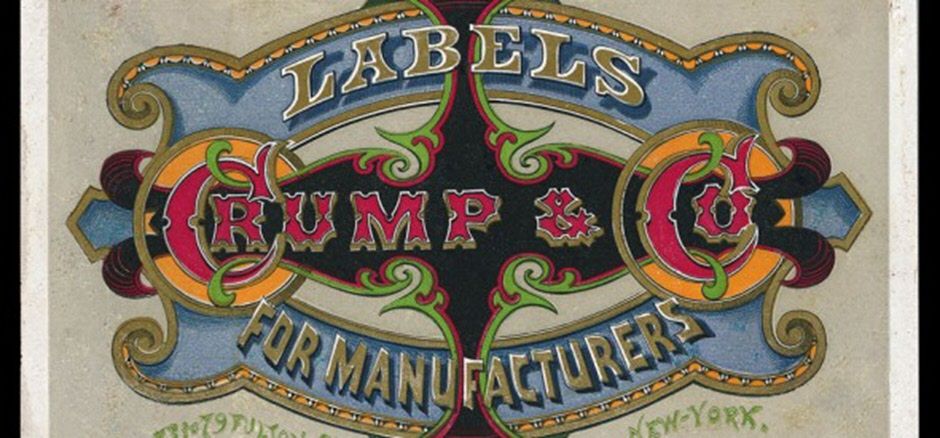

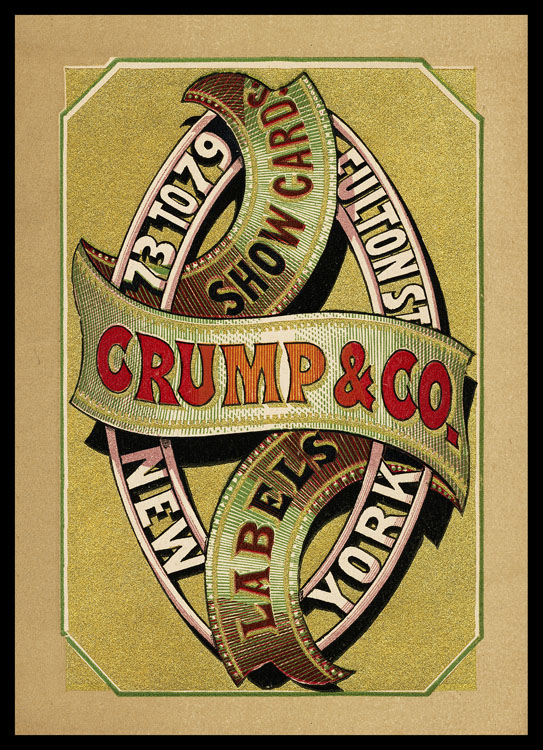

Recently I was contacted by a descendant of Samuel Crump, the well-known Victorian era printer and president of the Crump Label Company. The firm had been founded in 1832 by his father—also Samuel Crump, a wood engraver and printer in Montclair, NJ, an immigrant from Wales. Crump senior retired in 1861. From 1875 to 1878, the firm was Crump & Everdell, subsequently the Crump Label Press. In 1891, Crump Label , Russell Morgan and other label manufacturers came together under the umbrella of the United States Printing and Lithographing Company.

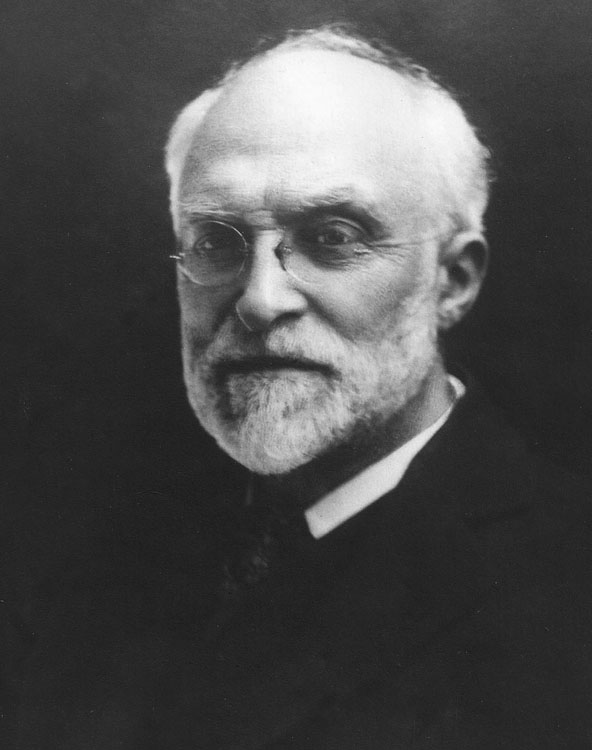

Samuel Crump (portrait courtesy of his great-granddaughter Patty Hoenigman)

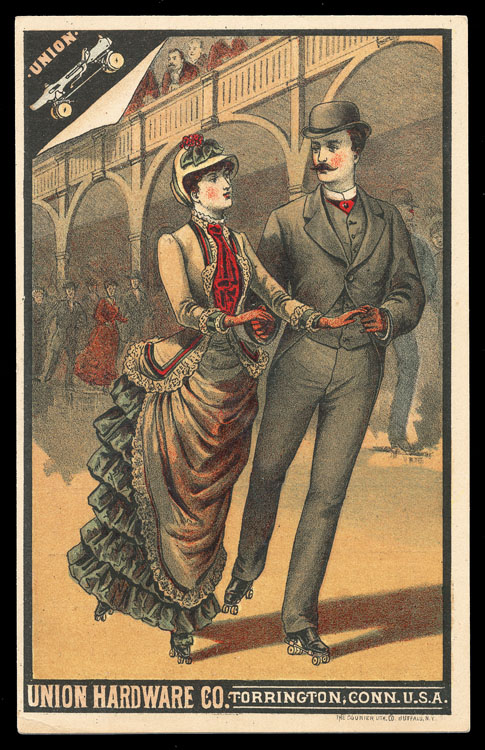

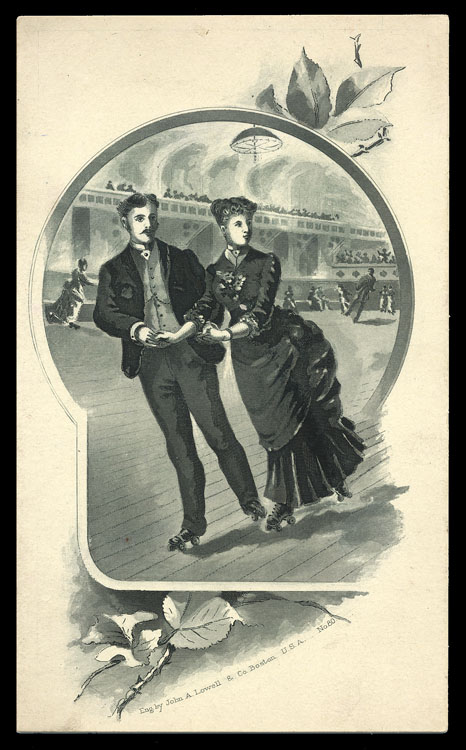

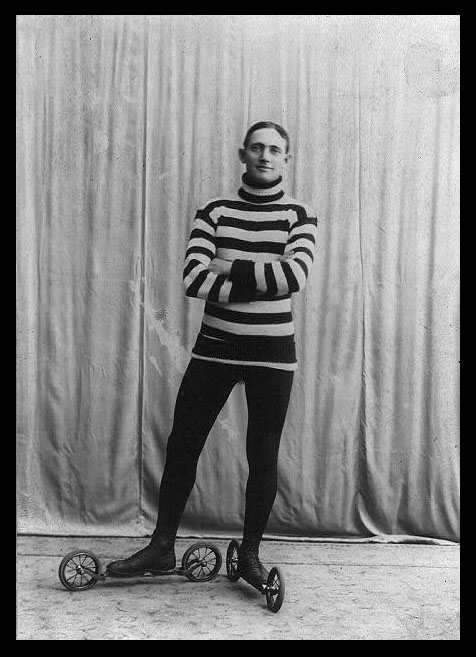

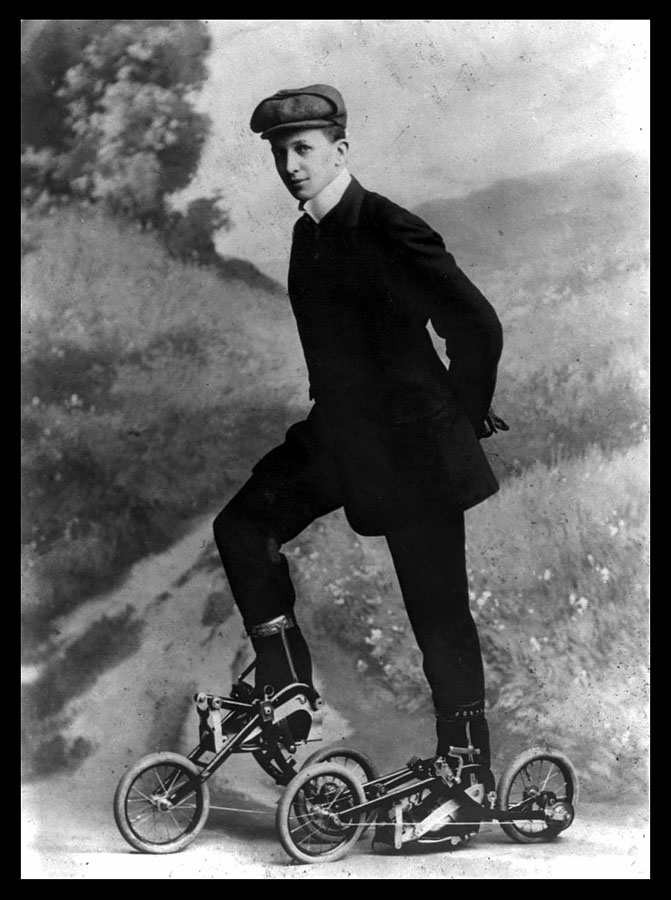

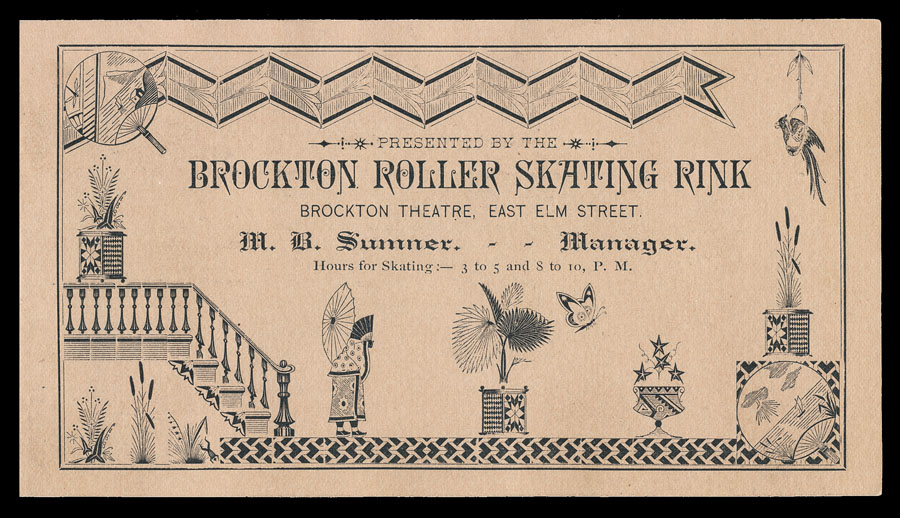

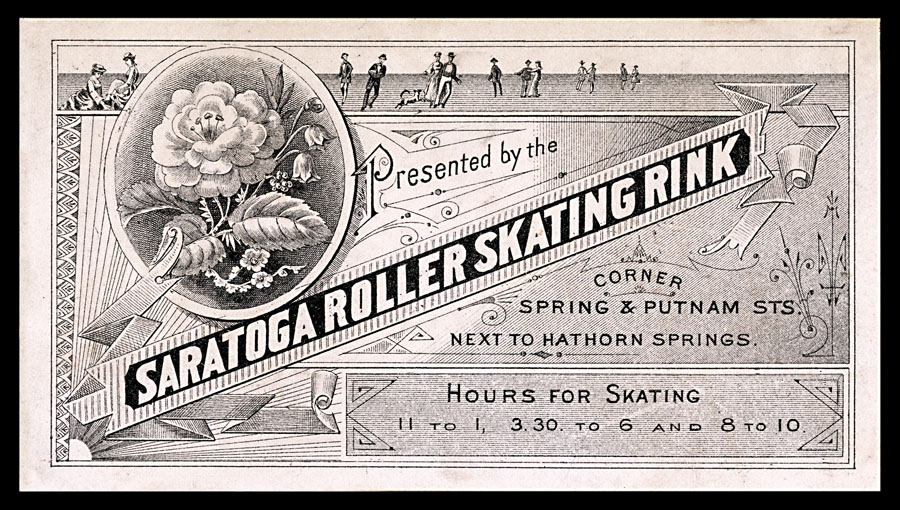

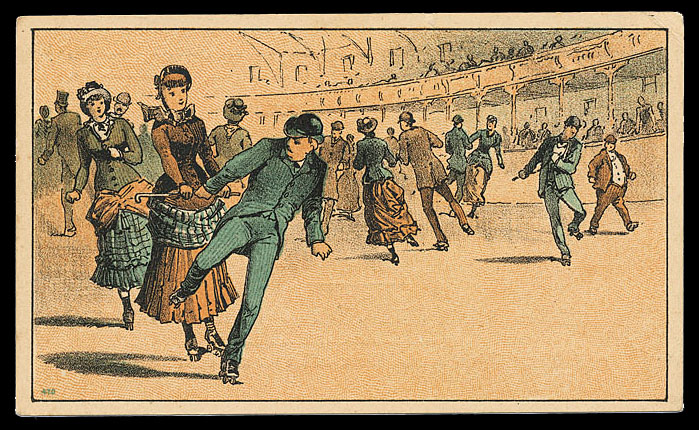

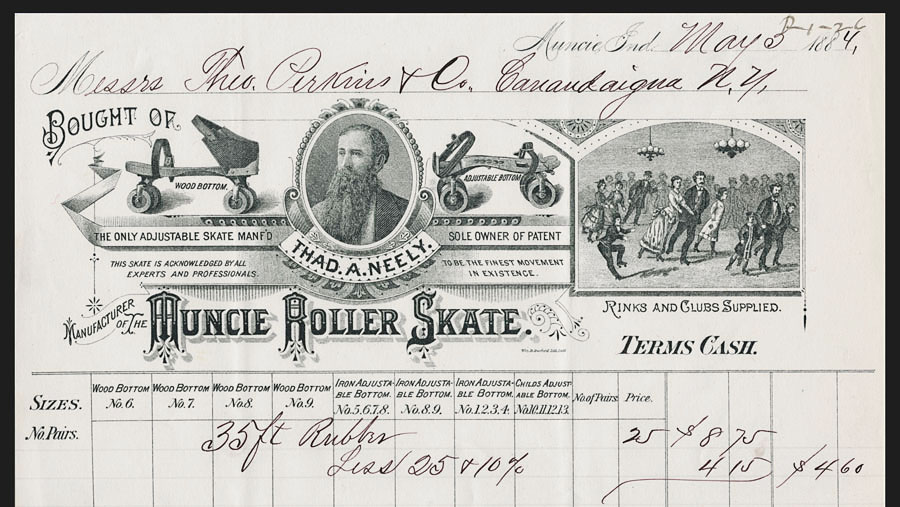

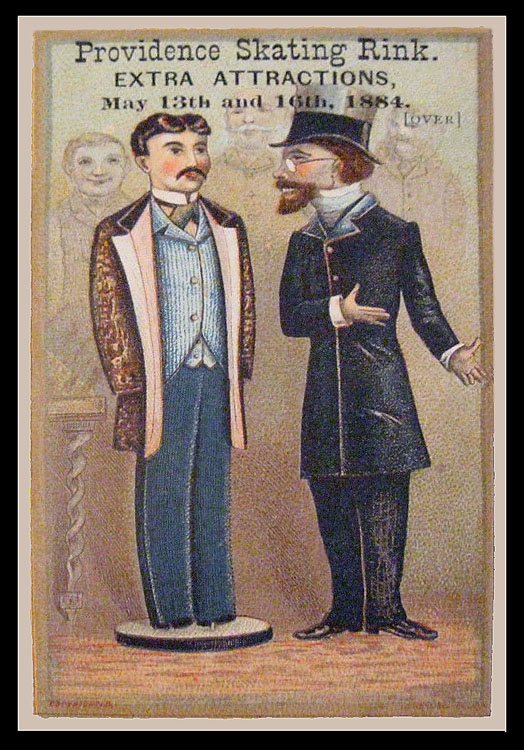

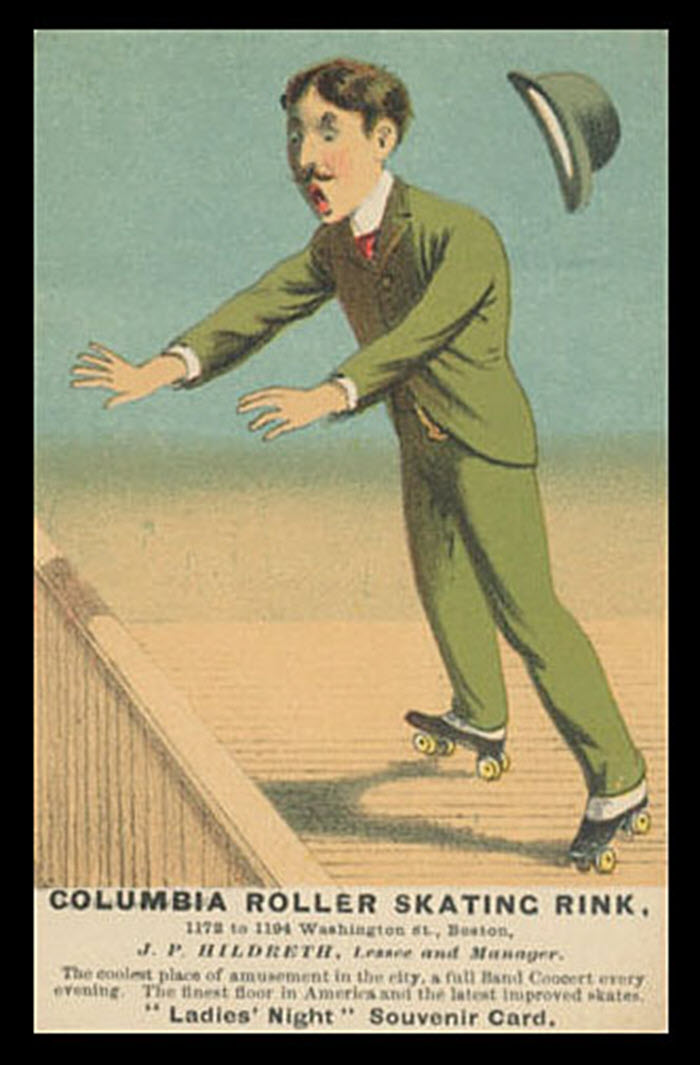

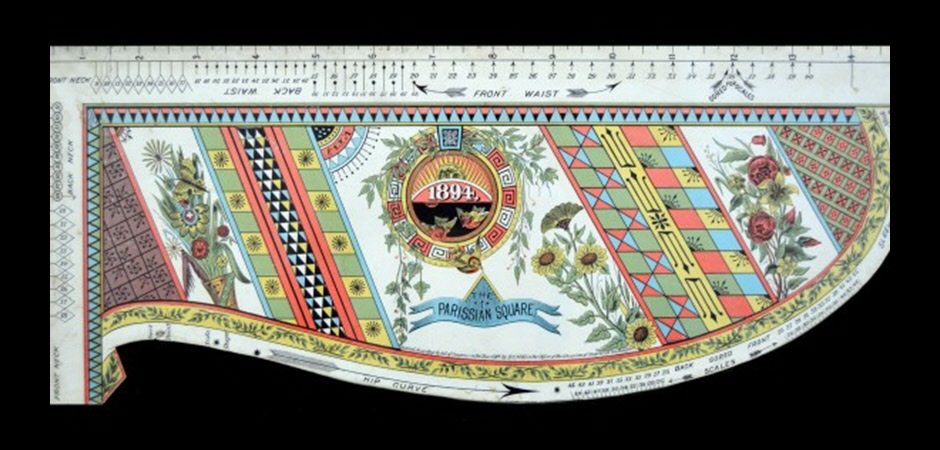

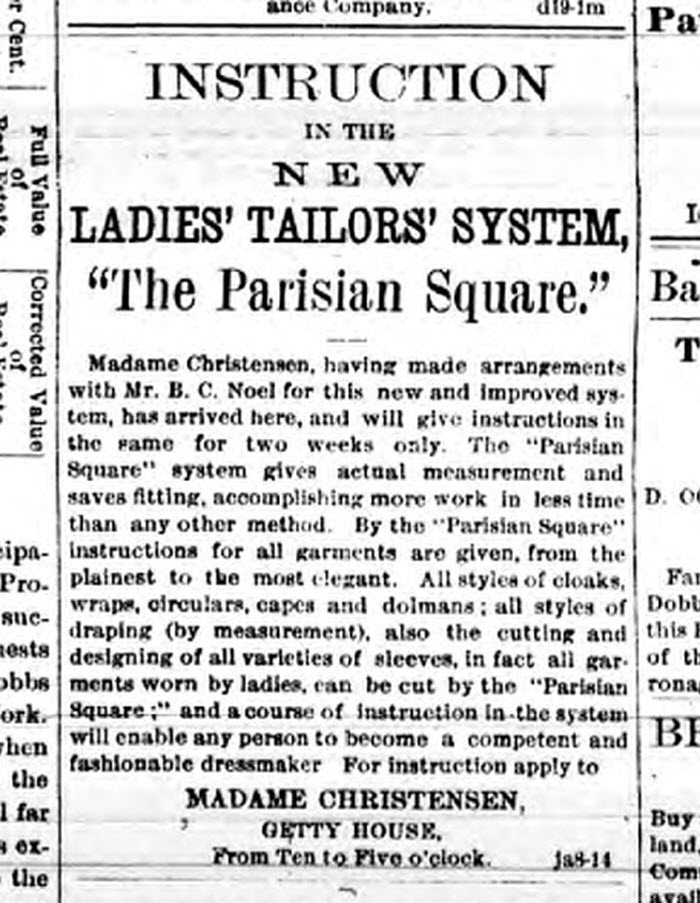

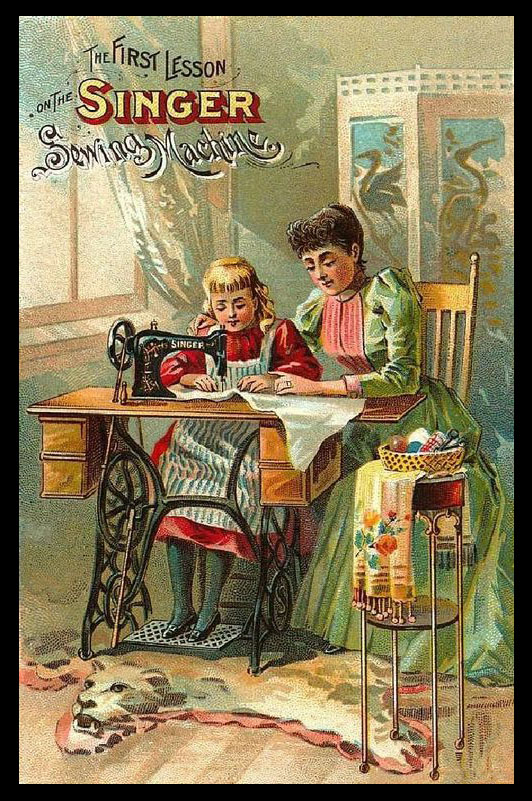

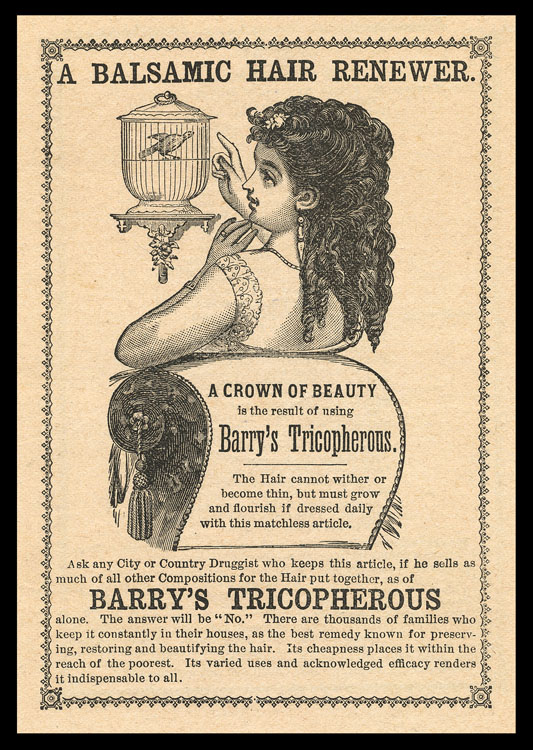

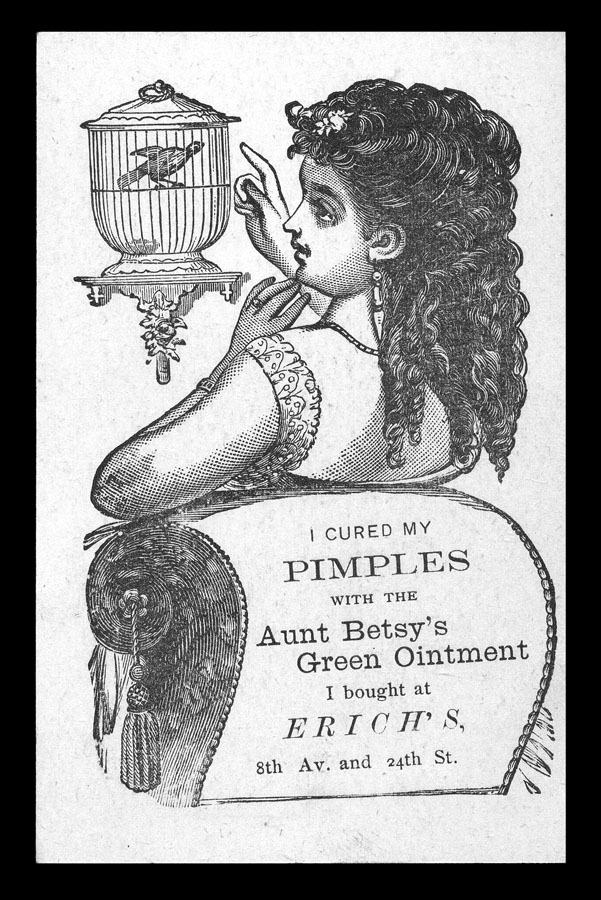

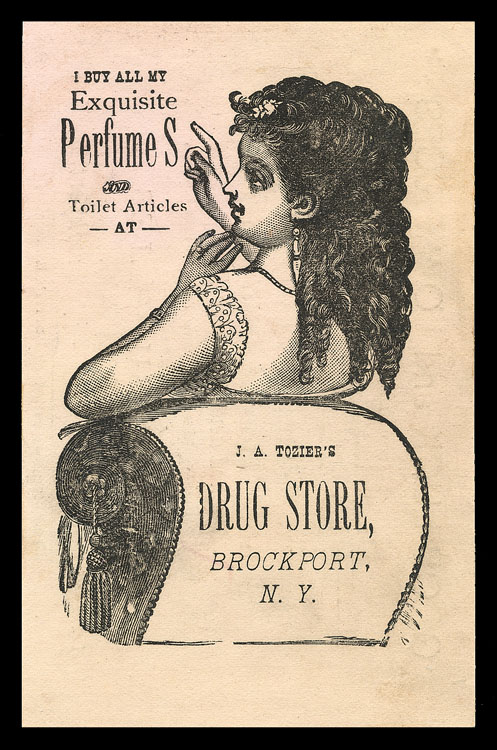

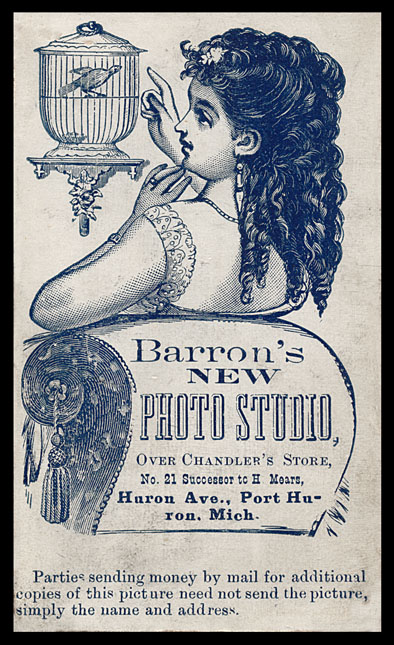

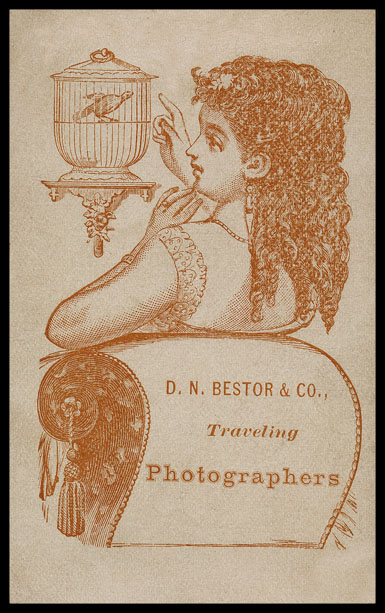

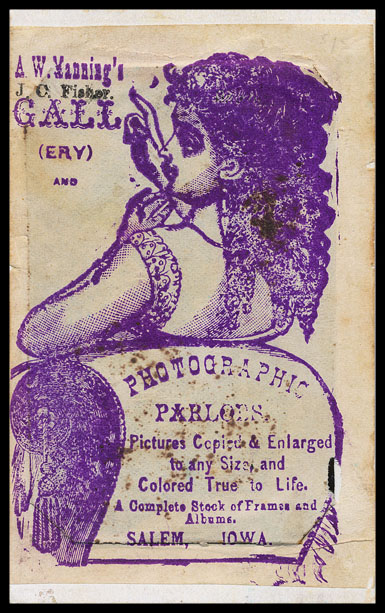

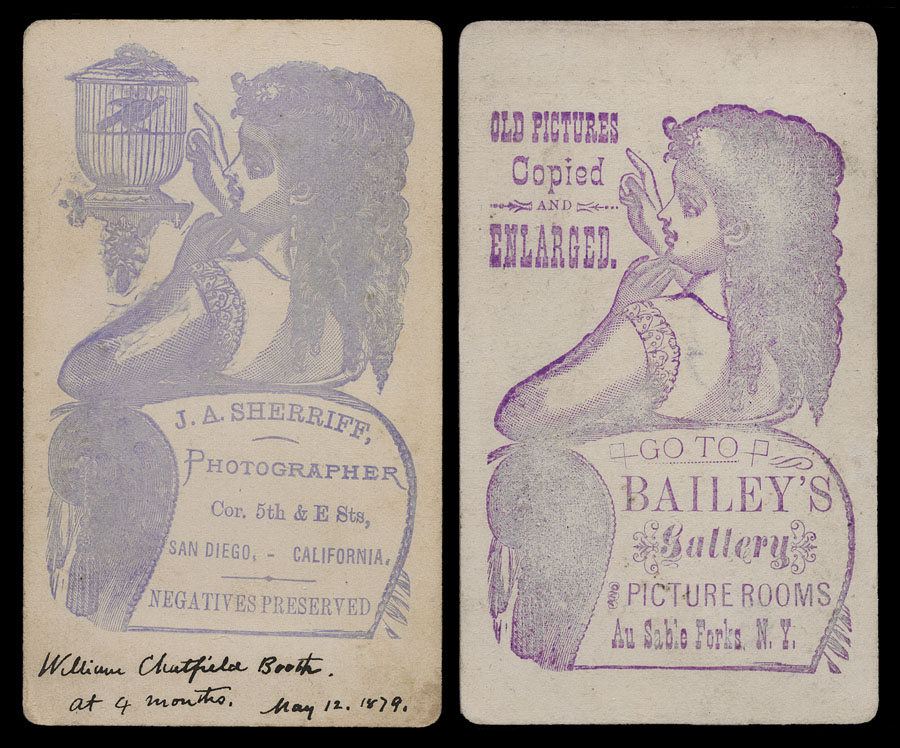

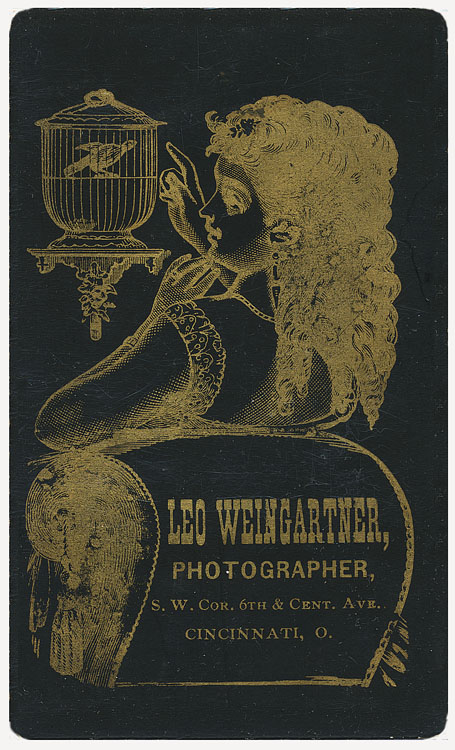

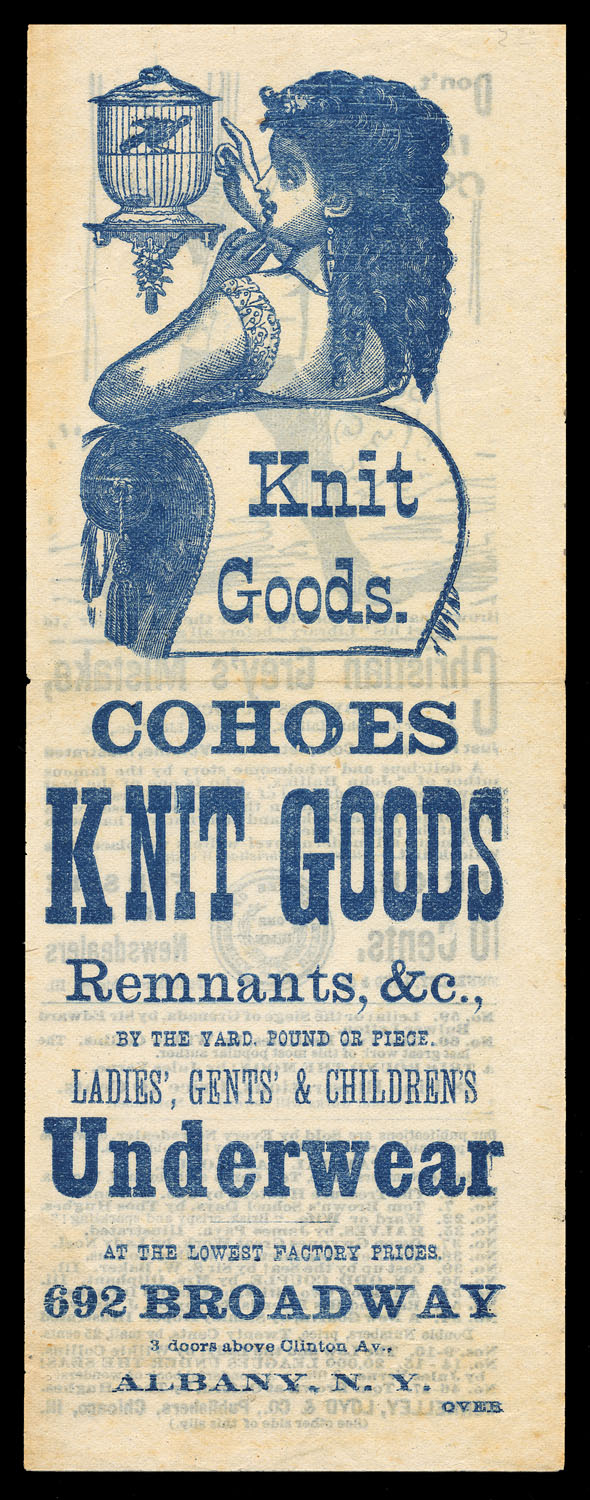

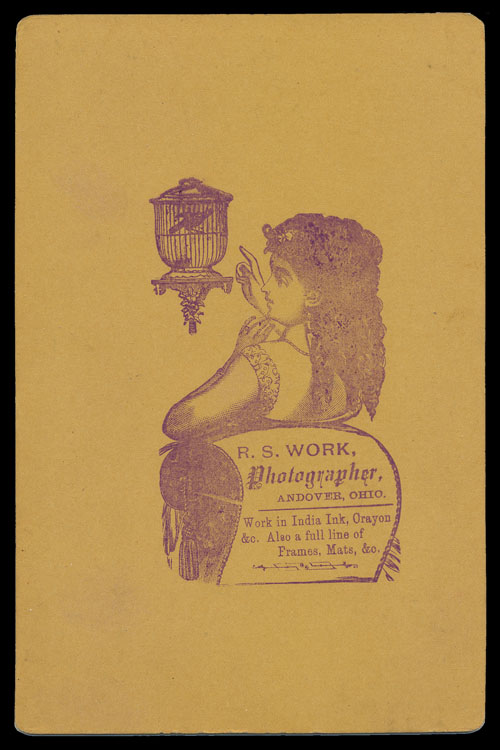

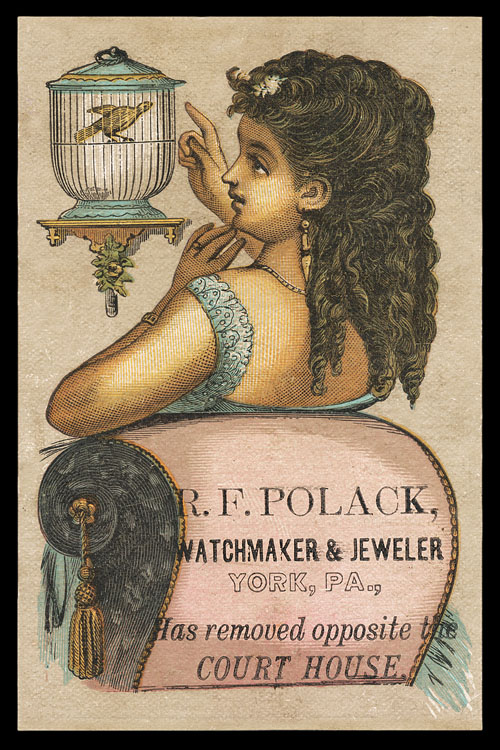

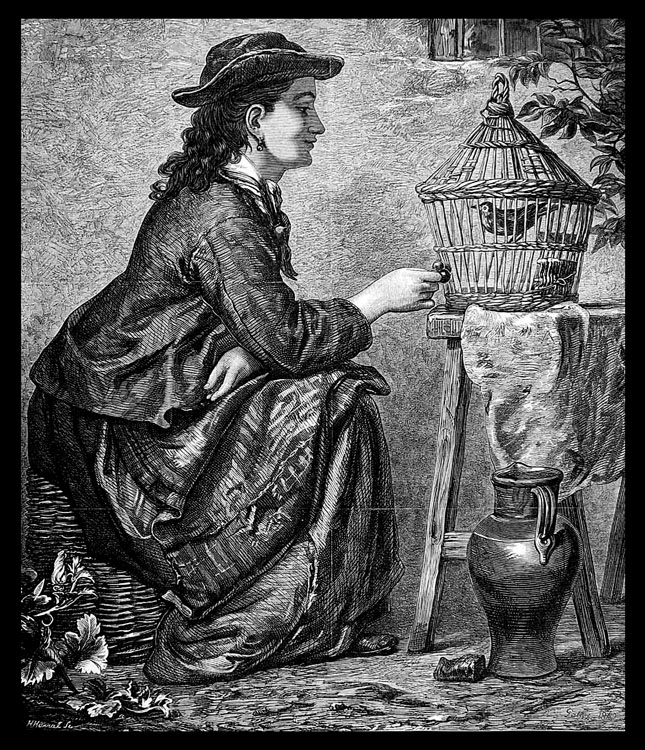

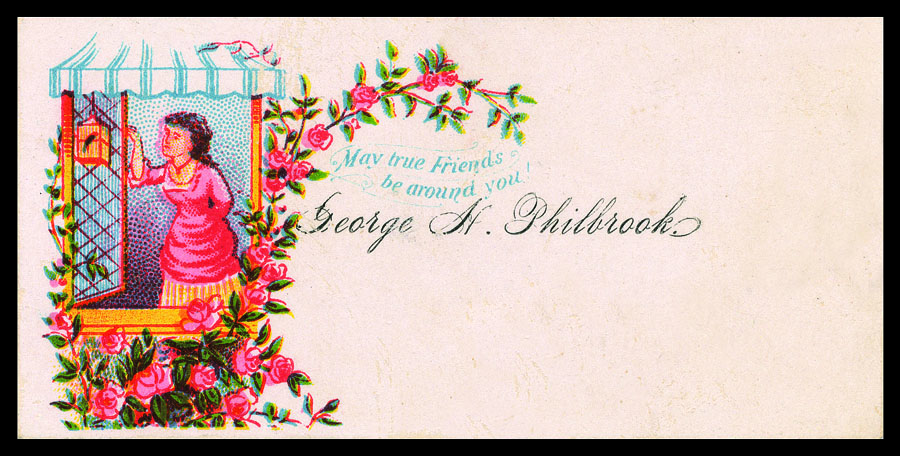

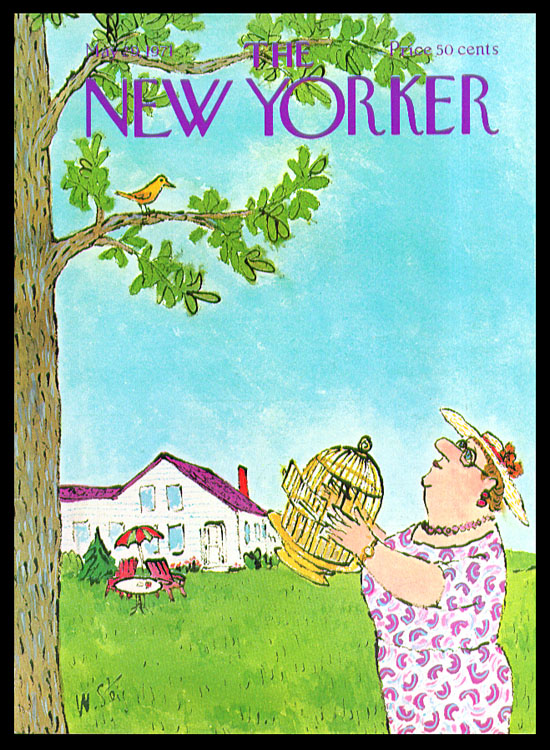

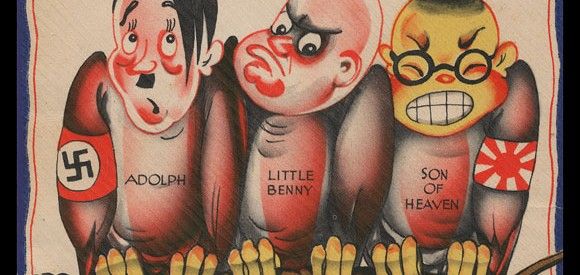

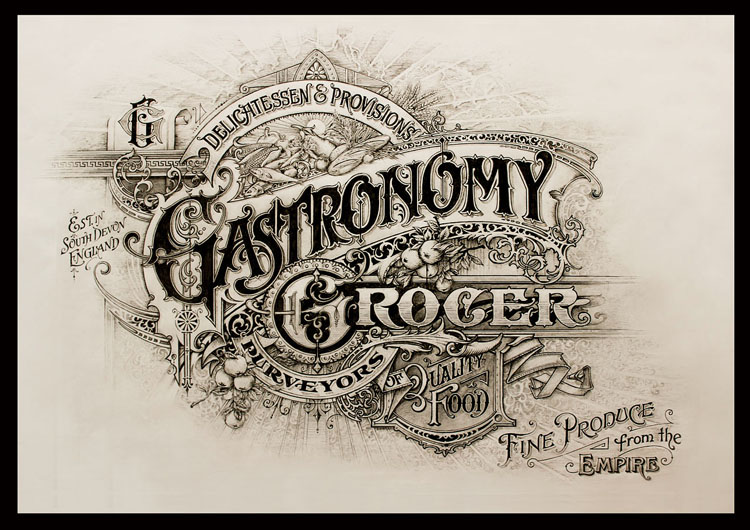

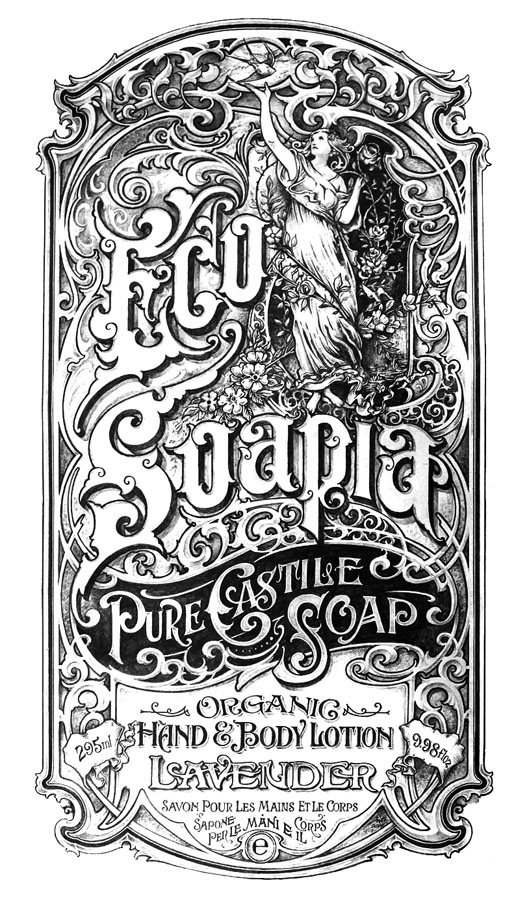

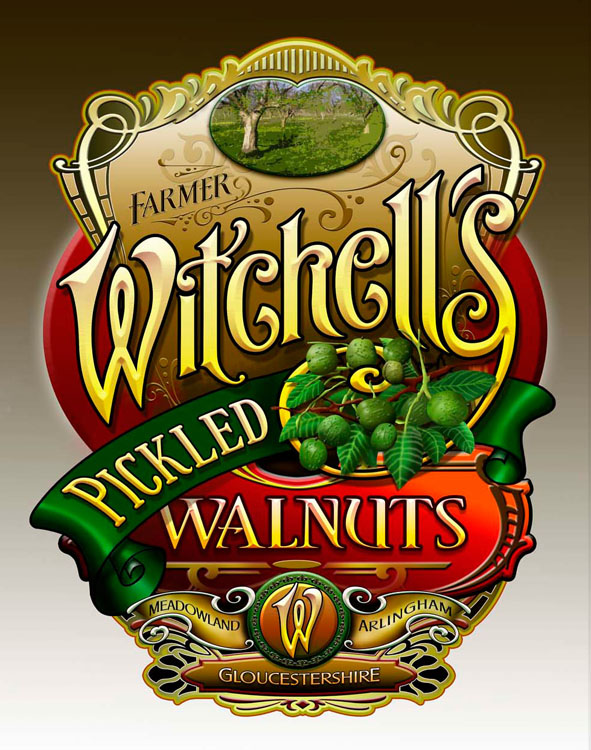

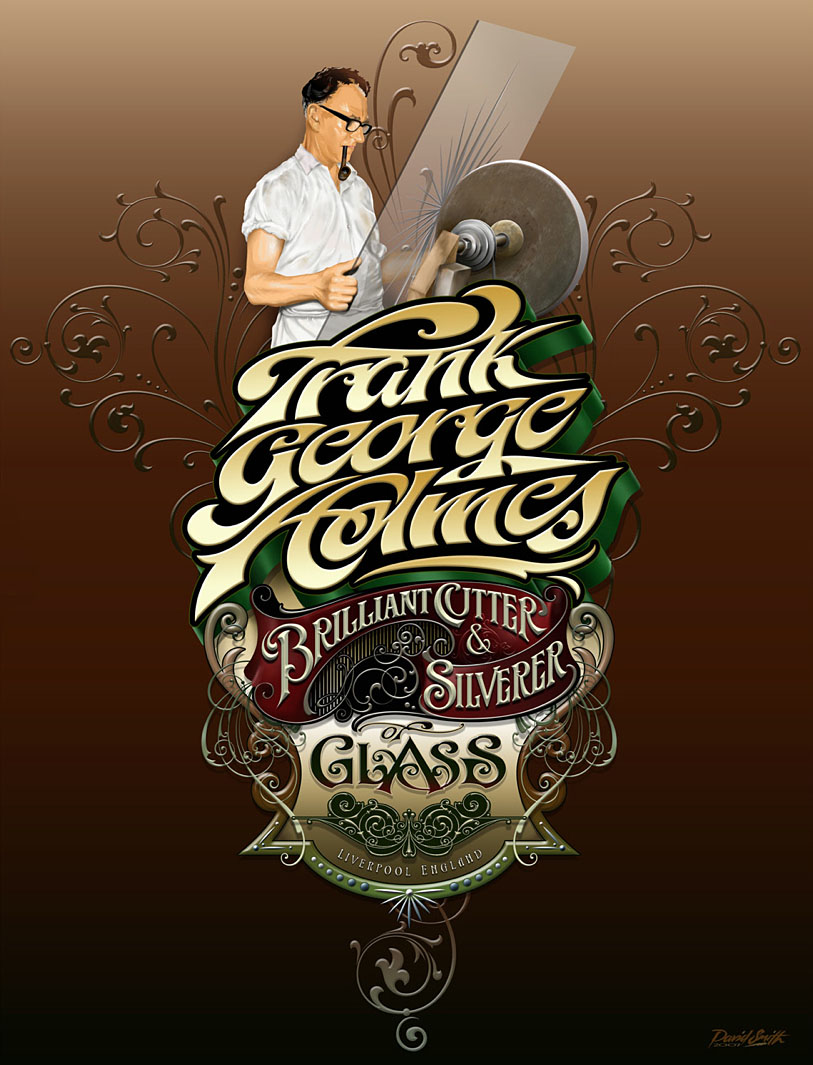

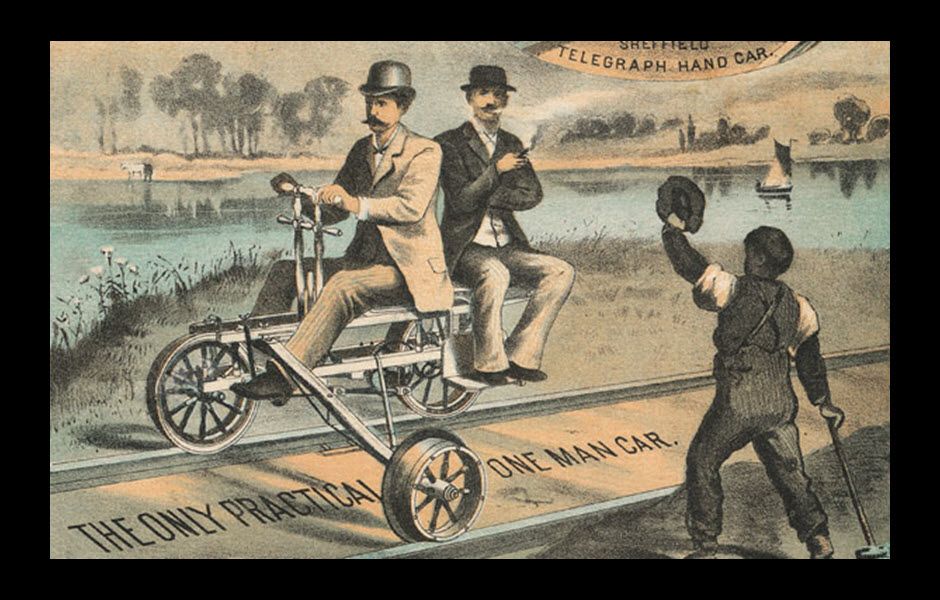

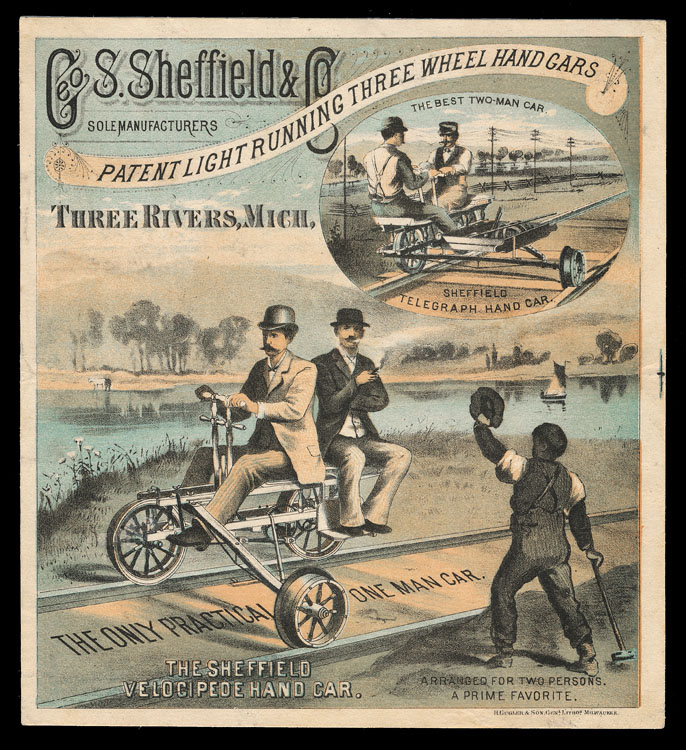

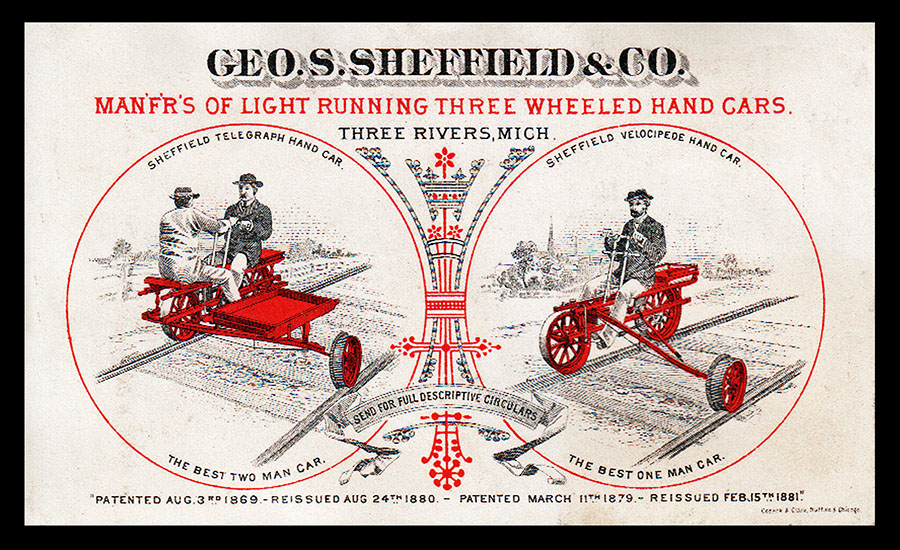

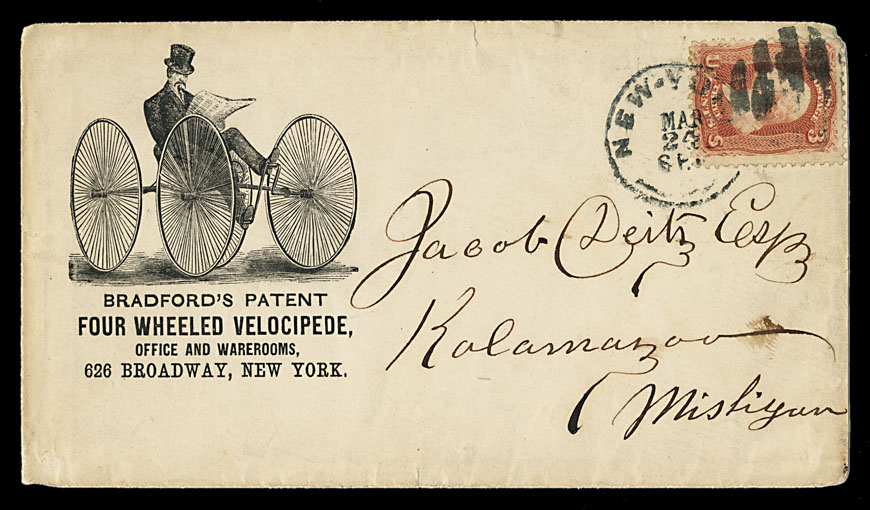

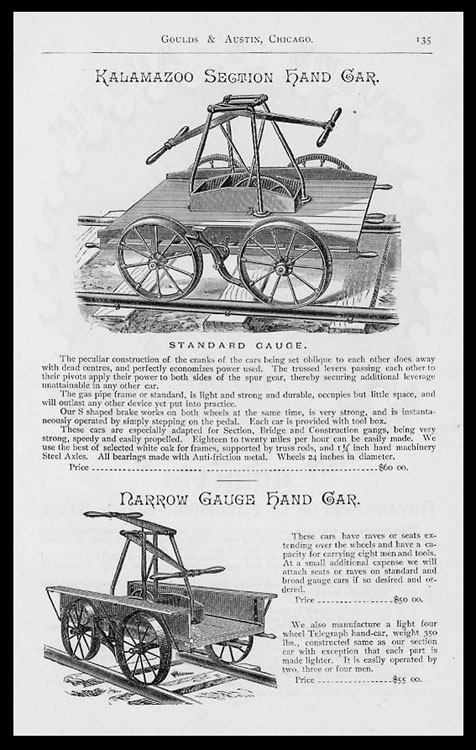

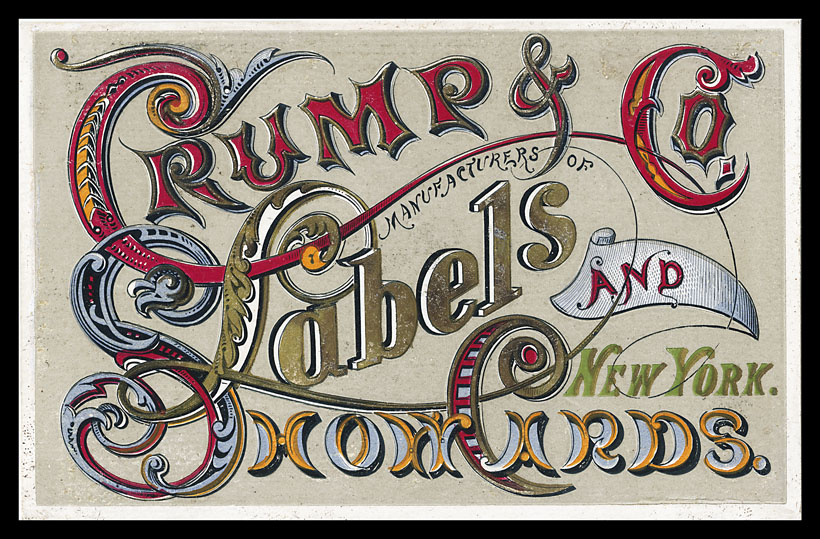

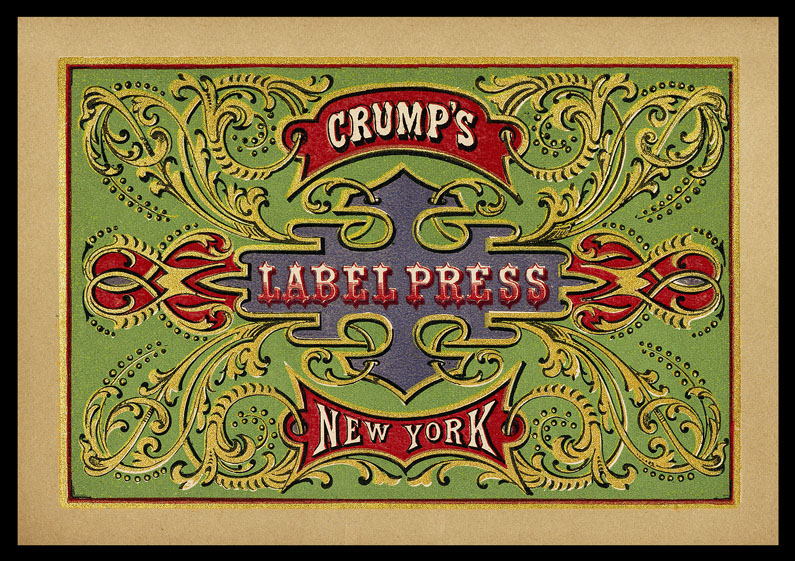

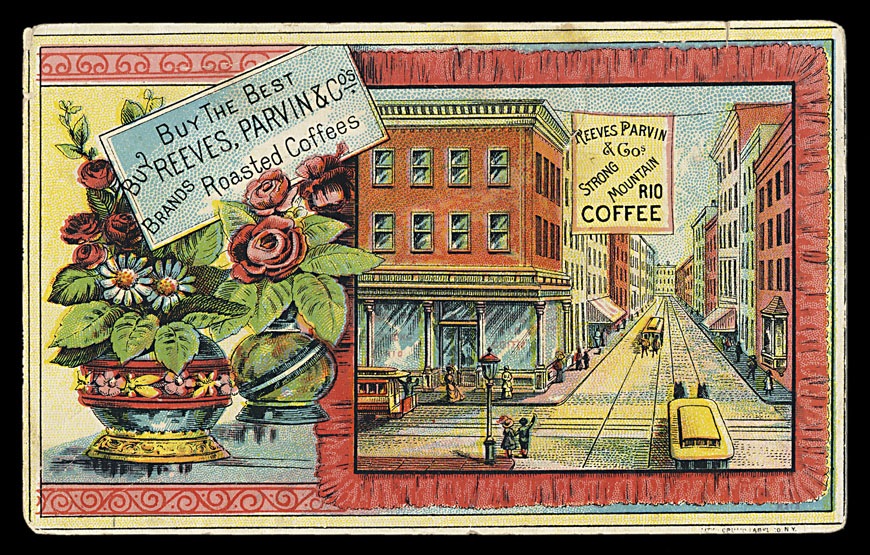

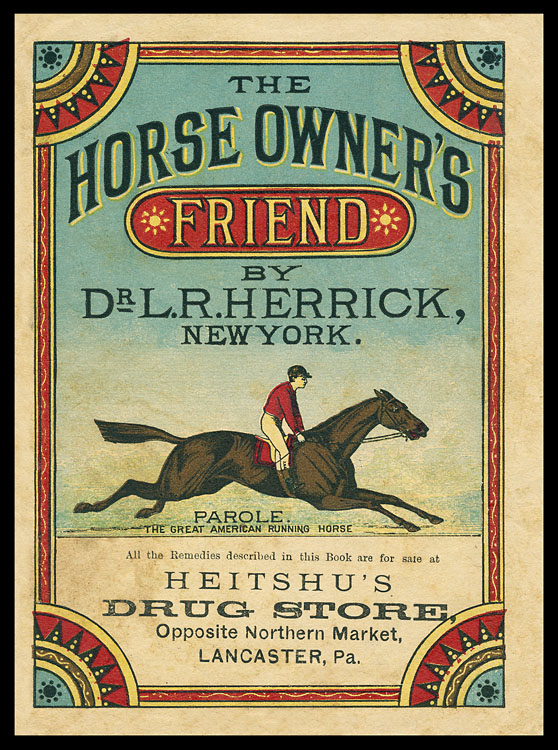

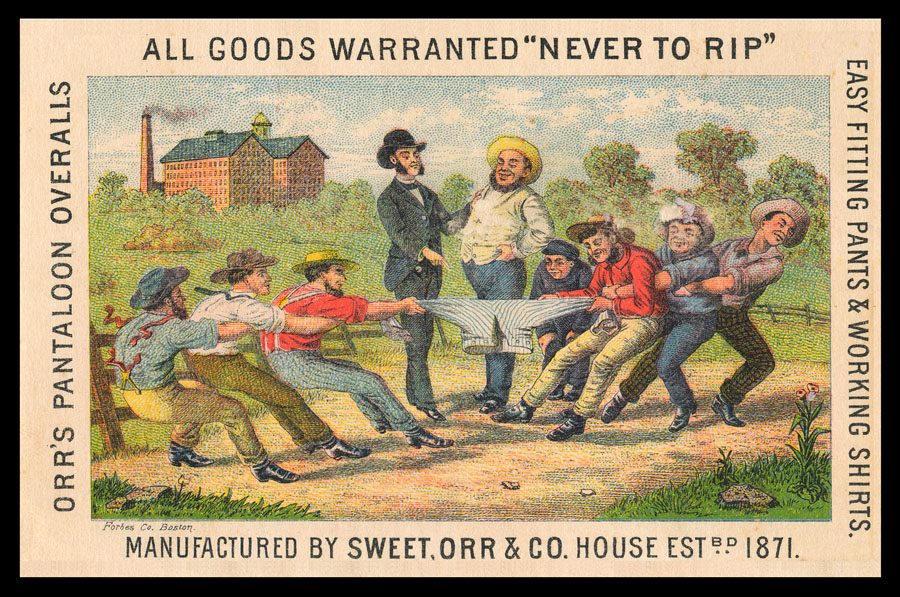

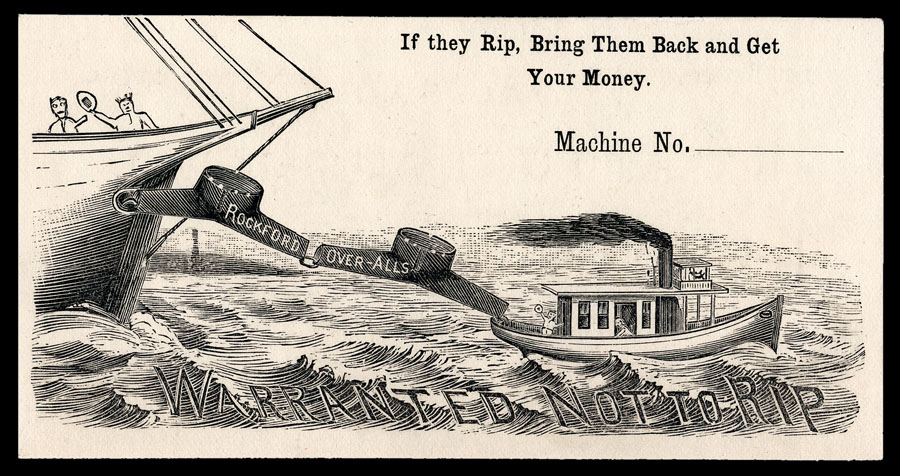

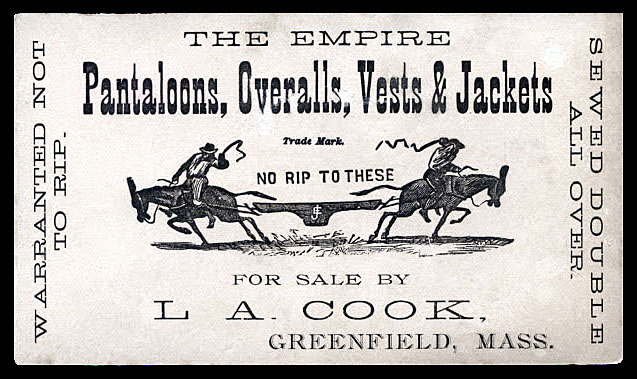

Many of today’s collections hold examples of trade cards and other items printed by Crump, and/or promotional materials for the Crump firm itself. I show a few examples of Crump pieces here, but my main reason for writing this short article is to present various interesting miscellaneous facts and anecdotes about Crump, a bit of the rich family lore. I have not fact-checked much of this, so simply pass it along for those who may have an interest.

It is said that the elder Samuel Crump emigrated to the United States from Wales and that he put together a printing press for a Brooklyn, NY newspaper before going into business on his own. By the Victorian era, Crump Label was printing one million labels per day! In 1881 alone, the firm shipped over 200 million labels, despite an ongoing economic depression.

The Crump operation became entirely self-sufficient on-site, manufacturing its own paper and inks and furnishing its own power. It employed some 190 skilled workmen. One contemporary description states that Crump labels “are printed in from one to ten colors inclusive, and present an attractive appearance. The higher grades are given a fine gloss or glaze, which greatly enhances their beauty. In fact, they surpass, in merit of design and beauty of finish, many chromos occupying places on the walls of some American homes.” (Industries of New Jersey, Part V, Historical Publishing Company, 1882)

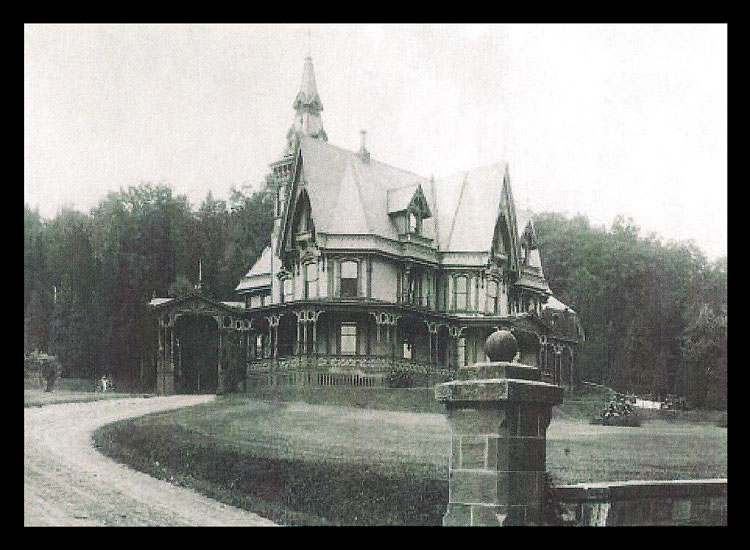

As his success grew, Samuel the younger built an exceptional gingerbread Victorian house and home in Montclair, NJ. The family—Crump, his pregnant wife Anna and four children—moved in in 1875. The Crumps eventually had 12 children, six of whom died young, another was killed fighting in WWI.

The Crump house in Montclair, NJ

Interestingly, in 1880 Crump hired a professional sanitary engineer to thoroughly inspect their house to try to identify the source of an outbreak of diphtheria. I have a copy of the report submitted by that engineer, Charles F. Wingate, which goes into fine detail about the site, the land’s pre-existing uses, the Crump cesspool septic system, and its vents, etc. He concluded that the house’s systems were fine, but that kitchen slop and other vegetable and animal matter simply tossed outside on the ground, as was commonplace in the day, might well have been a factor in causing diphtheria.

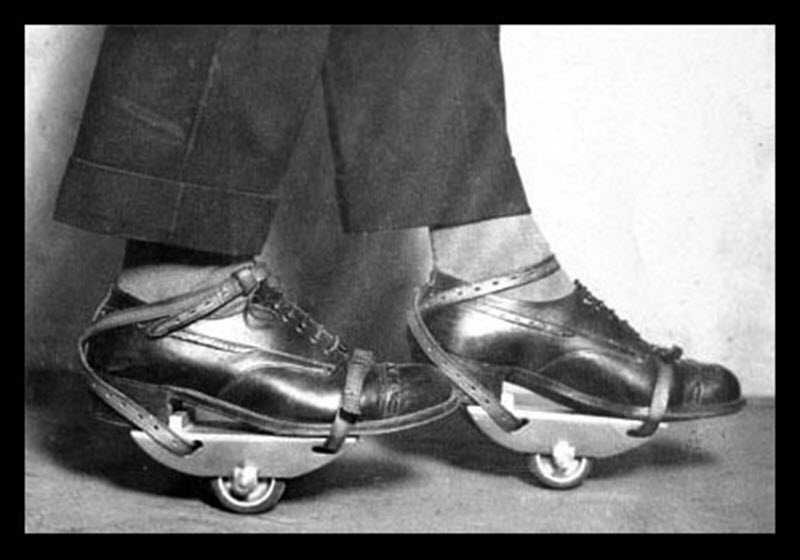

Crump had a number of eccentricities. It is said that he hung his blankets from the ceiling so that they would not touch him, sometimes wore suits made of paper, drilled holes in the tops of his shoes to admit air. After trips to the Far East, Hawaii and Australia Crump became so interested in coconuts that he set up an operation to can and distribute coconut meat, but that something went wrong and his canned products often exploded. Late in life, he attempted to create a water-based newspaper ink that would not rub off.

Family lore has it that Crump at some point sold the business, moved out West, then returned to New York after losing all his money. He died in Shanghai, China while visiting a daughter who lived there.

George Inness, The Mill Stream, Montclair, New Jersey, c1888. Inness moved to Montclair in 1878. In the background of this painting appears the Crump factory complex. “Far from making a statement on the negative aspects of industrial encroachment, Inness used the factory to portray the “civilized landscape” in which vistas of nature are enhanced by signs of mankind’s progress. The artist bent all his artistic powers to support this theory, uniting composition, color, light, and mood to infuse into his industrial landscape a lyricism that echoes the idyllic pastoral landscapes of Claude Lorrain.” (Minneapolis Institute of Arts)