Author: Diane DeBlois

Architecture and the Photo Studio

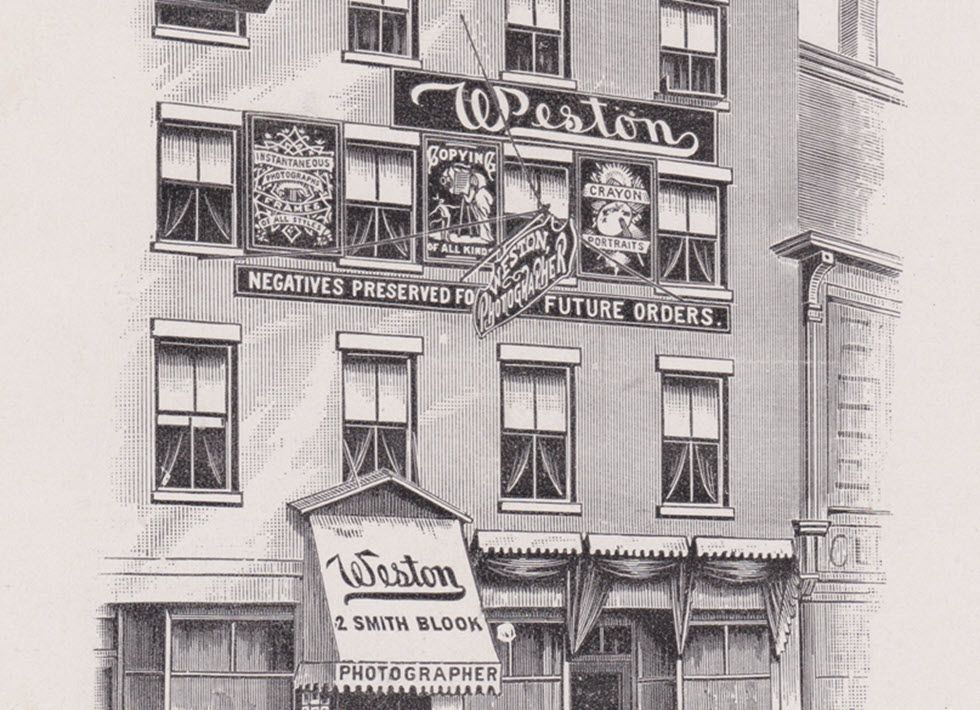

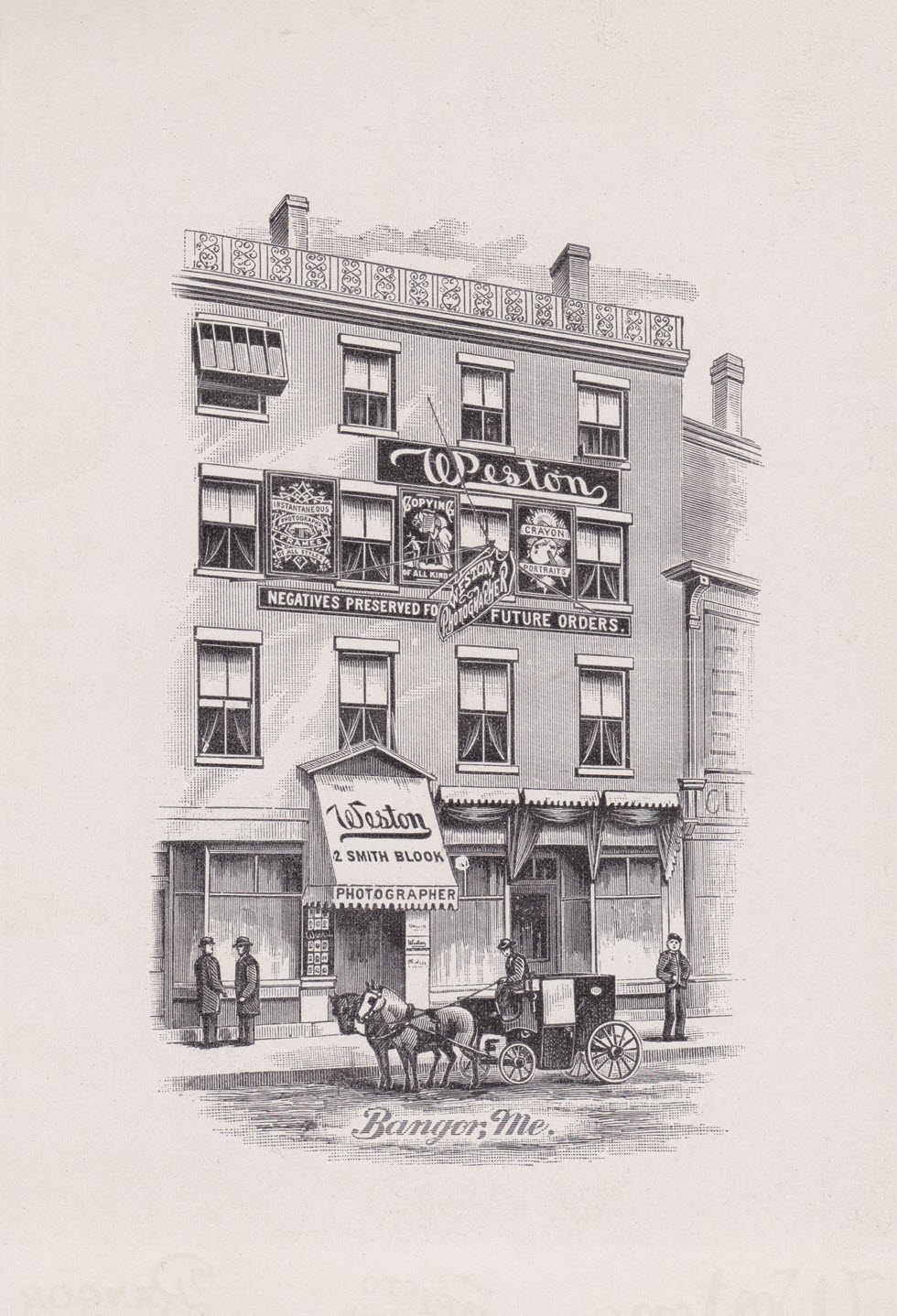

The expanding popularity of inexpensive photographic portraits of the “cabinet” size (4.25 x 6.5 inches) in the 1880s and 1890s increased competition among photographers. The printed backs of the portrait card offered a prime venue for advertising; not just text but often an architectural rendering of the photographer’s studio. For us it is an opportunity to examine alterations to a building to improve photographing conditions, and to note signage and other promotions.

(1) Frank C. Weston of Bangor, Maine established his studio on the upper two floors of the Smith Block. To make sure that prospective clients knew the exact location, he had mounted a large sign between the third and fourth floor facades, and a swing sign pendant from the center of four windows on each of those floors. Between the windows of the third floor he mounted illustrated “poster” signs that detailed his specialties: “Instantaneous photographs; frames of all styles” “Copying of all kinds” “Crayon portraits.” Despite other merchants occupying the other two floors, Weston had his name on the front door awning and a case of portrait examples on display to the left of the door. Photographers needed as much natural light as possible, and curious protrusions from two of the fourth floor windows (especially the multi-paned box on the far left) were built to direct more light to the studio.

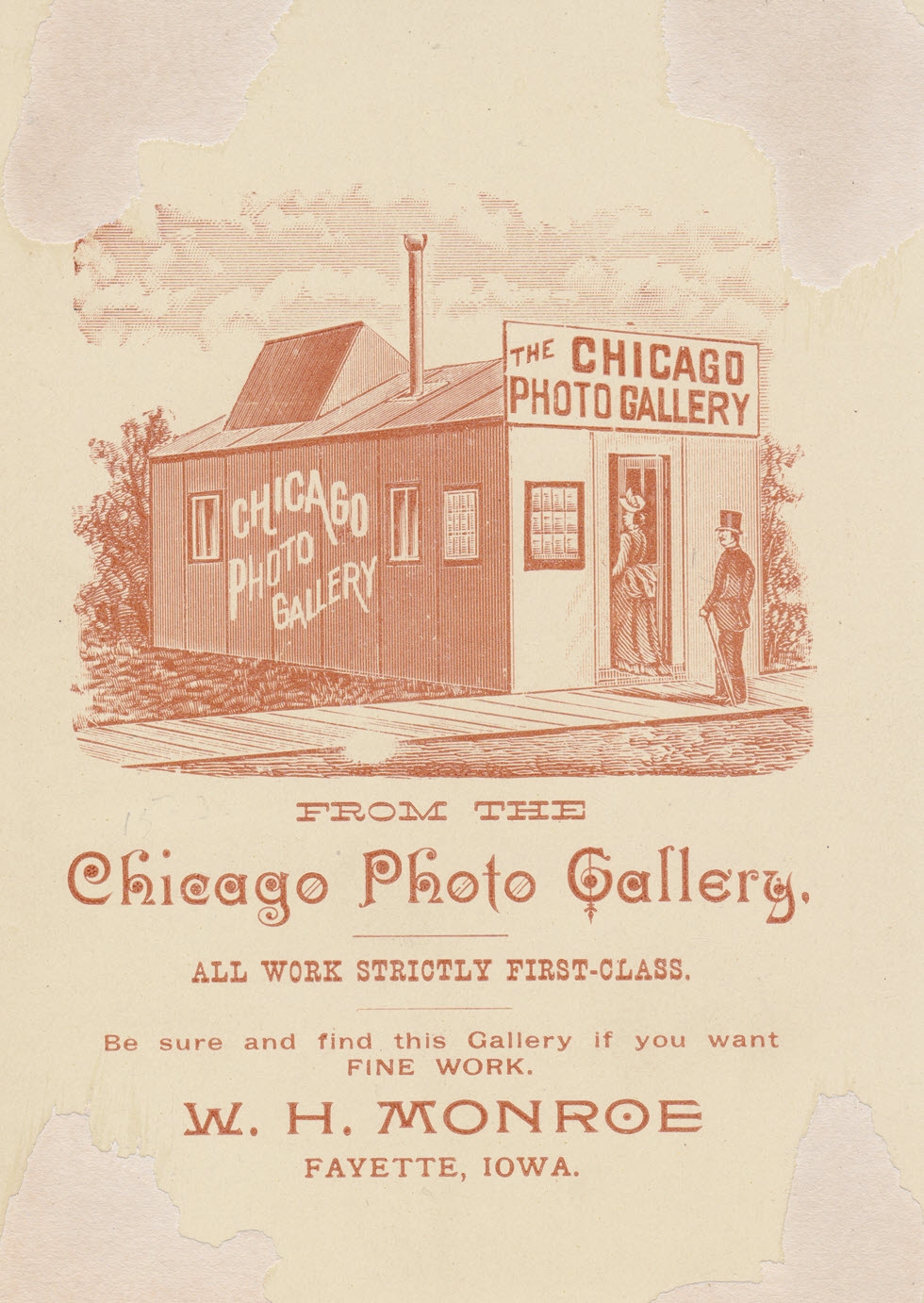

(2) Alterations to existing buildings for increasing light appear in many of the cabinet card backs. The least elaborate was made by W.H. Monroe to his modest metal photo shack, proudly delineated “The Chicago Photo Gallery” in tiny Fayette, Iowa. An angled sky light has been let into the rolled tin roof – the better to photograph fashionably dressed women and gentlemen, shown entering the gallery, having passed over the board sidewalk.

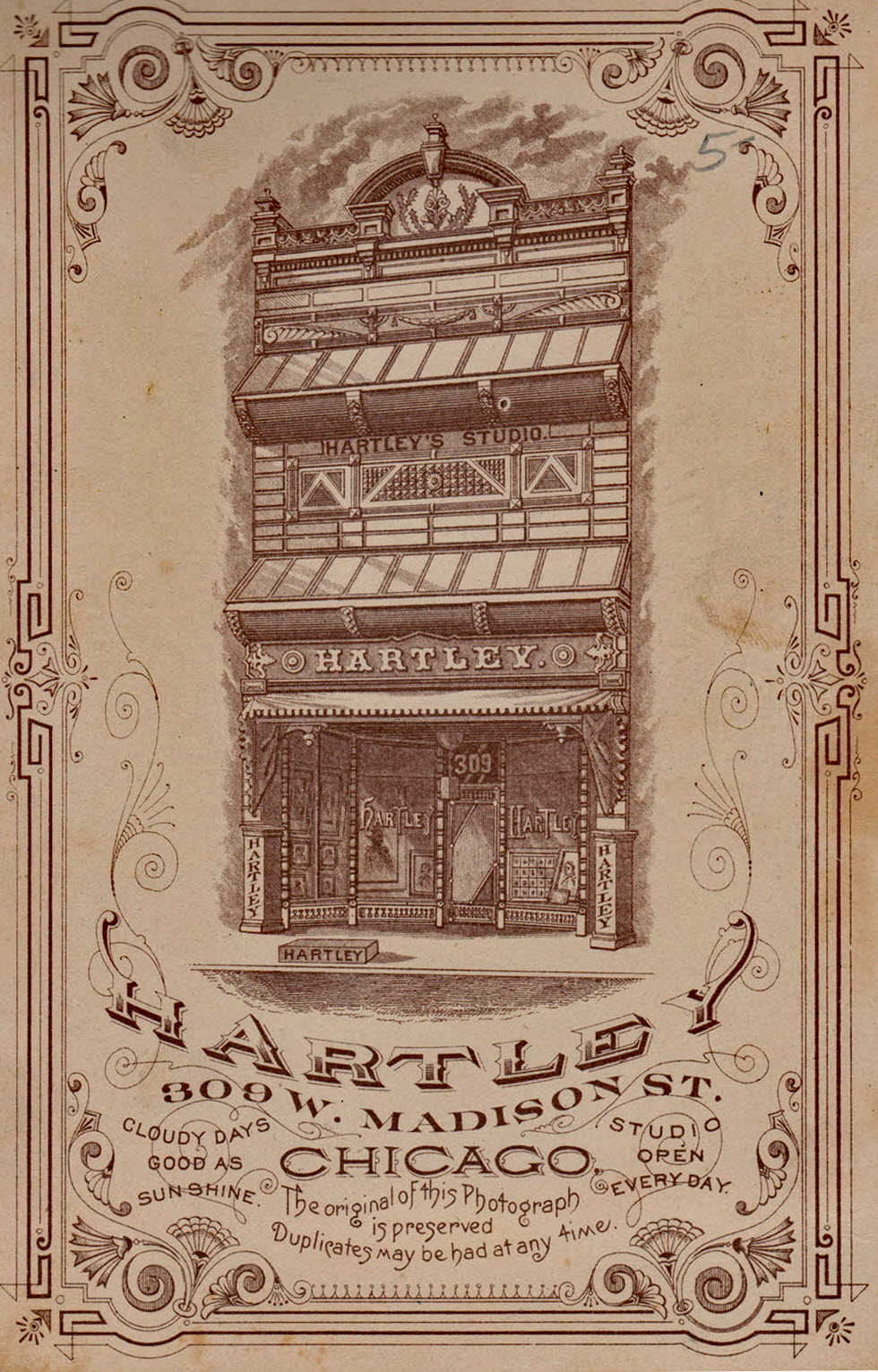

(3) In Chicago itself, Edward F. Hartley may have designed his three-story building at 309 West Madison specifically to light his photographs (made from 1875 to 1894). If he bought an existing structure, he certainly adapted it comprehensively: the windows on the second and third floors have been replaced by multi-pane ‘balconies’ of light scoops – allowing him to boast “cloudy days good as sunshine.” Harley placed his name in as many places on the building as possible: on the face between floors, on the sign above the entrance, on the curved glass of the lobby entrance, on the corner pillars and even on the mounting block on the sidewalk.

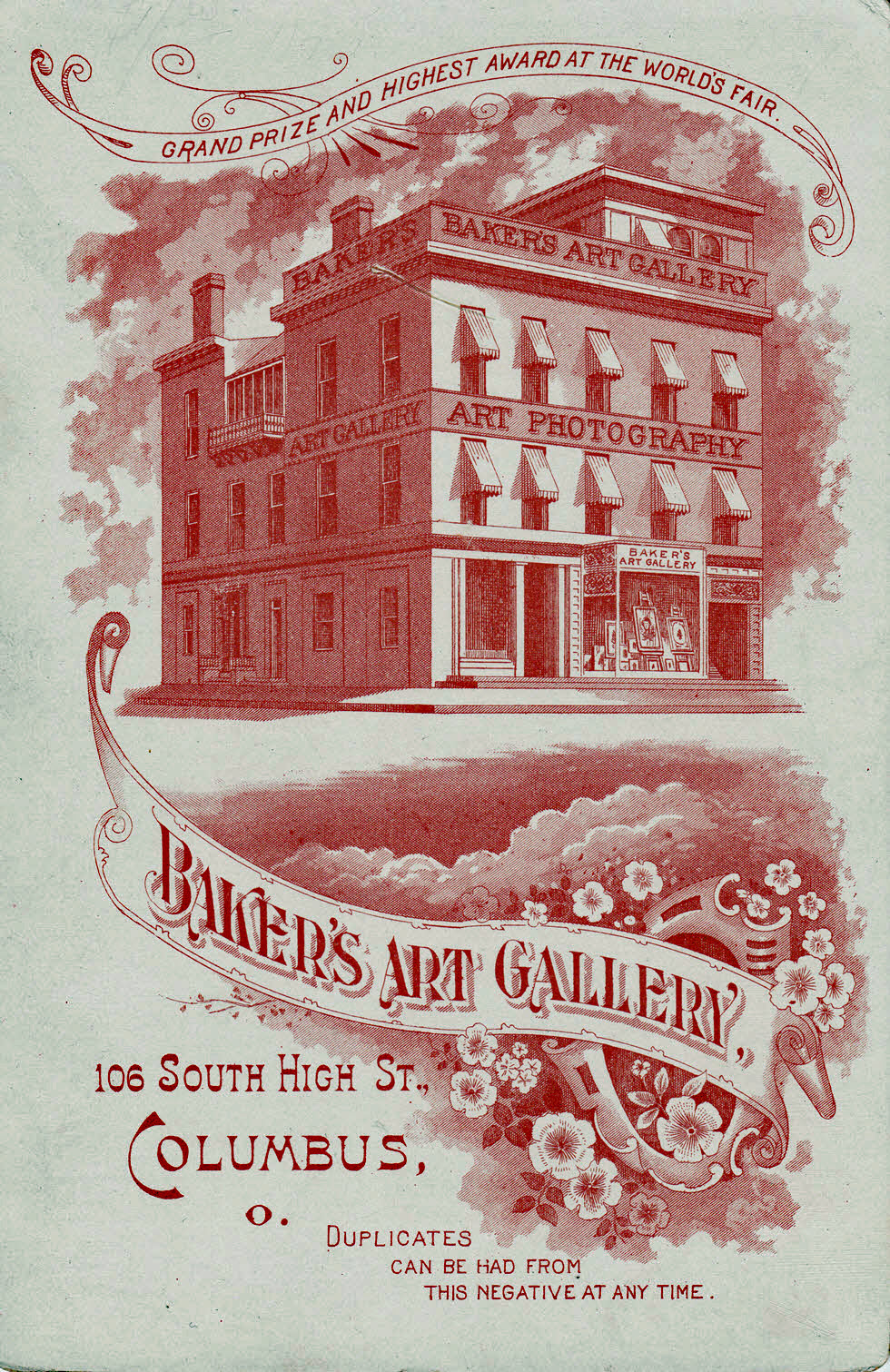

(4) In Columbus, Ohio Lorenzo Marvin Baker also chose a three-story building but on a corner, placing his “Art Gallery” and “Art Photography” on the top two floors, plus a penthouse. The top floor has a balcony with six tall windows that would provide more light, and the penthouse has slanted light reflectors. A photograph of the location around 1905 shows an even more elaborate light capturing structure built on top of the penthouse, and signs advertising the photography business filling in all the space between the windows on the second floor.

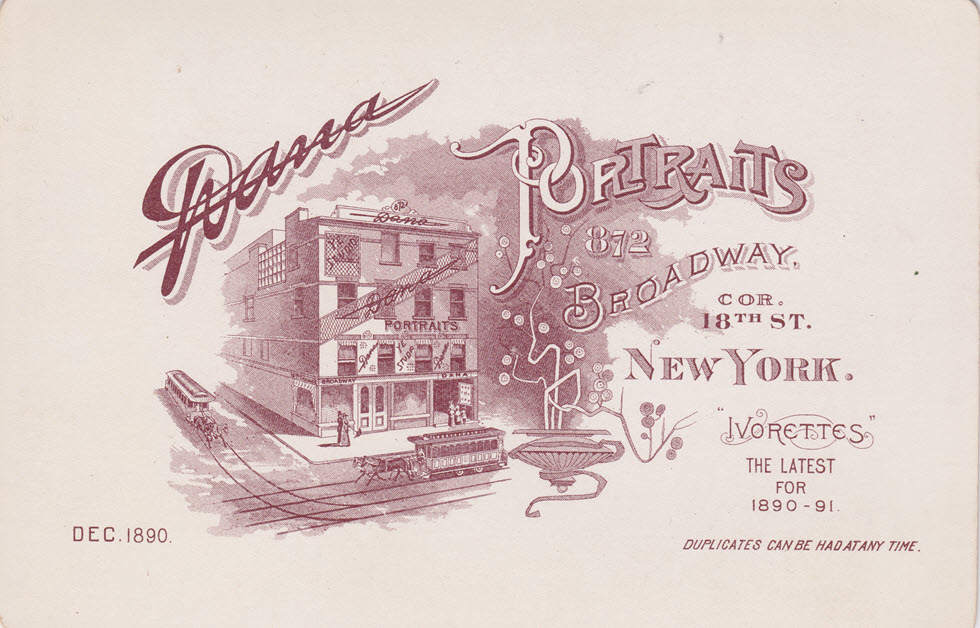

(5) One of the best known urban photographers, Edward Cary Dana established a four-story emporium at 872 Broadway – a corner building that he swathed in signs mounted on wire mesh. This was just one of eventually four studios – one that opened in Brooklyn in 1892 had a specially constructed 19 x 55 foot skylight with a west of north exposure. Here, in 1890 on the corner of 18th street, he has created an inset of 4 x 7 glass bricks for more light. To emphasize his artistic approach, this vignette is printed on the card back in landscape rather than portrait view.

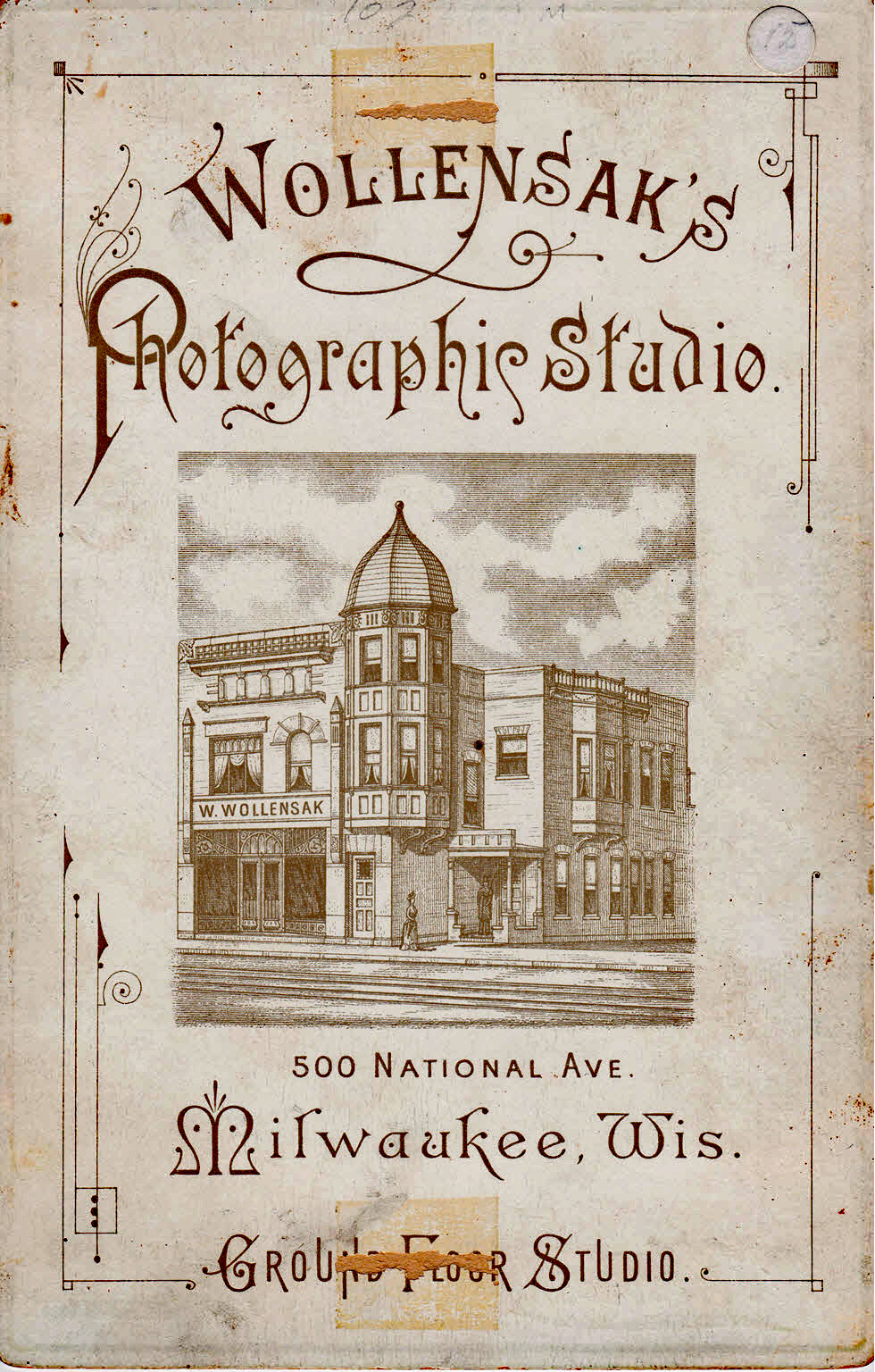

(6) Successful urban photographers could spread over more than one floor of a building. But several more modest establishments made a virtue of there being no stairs for clients to climb. William Wollensack’s studio at 500 National Avenue in Milwaukee was promoted as being on the ground floor.

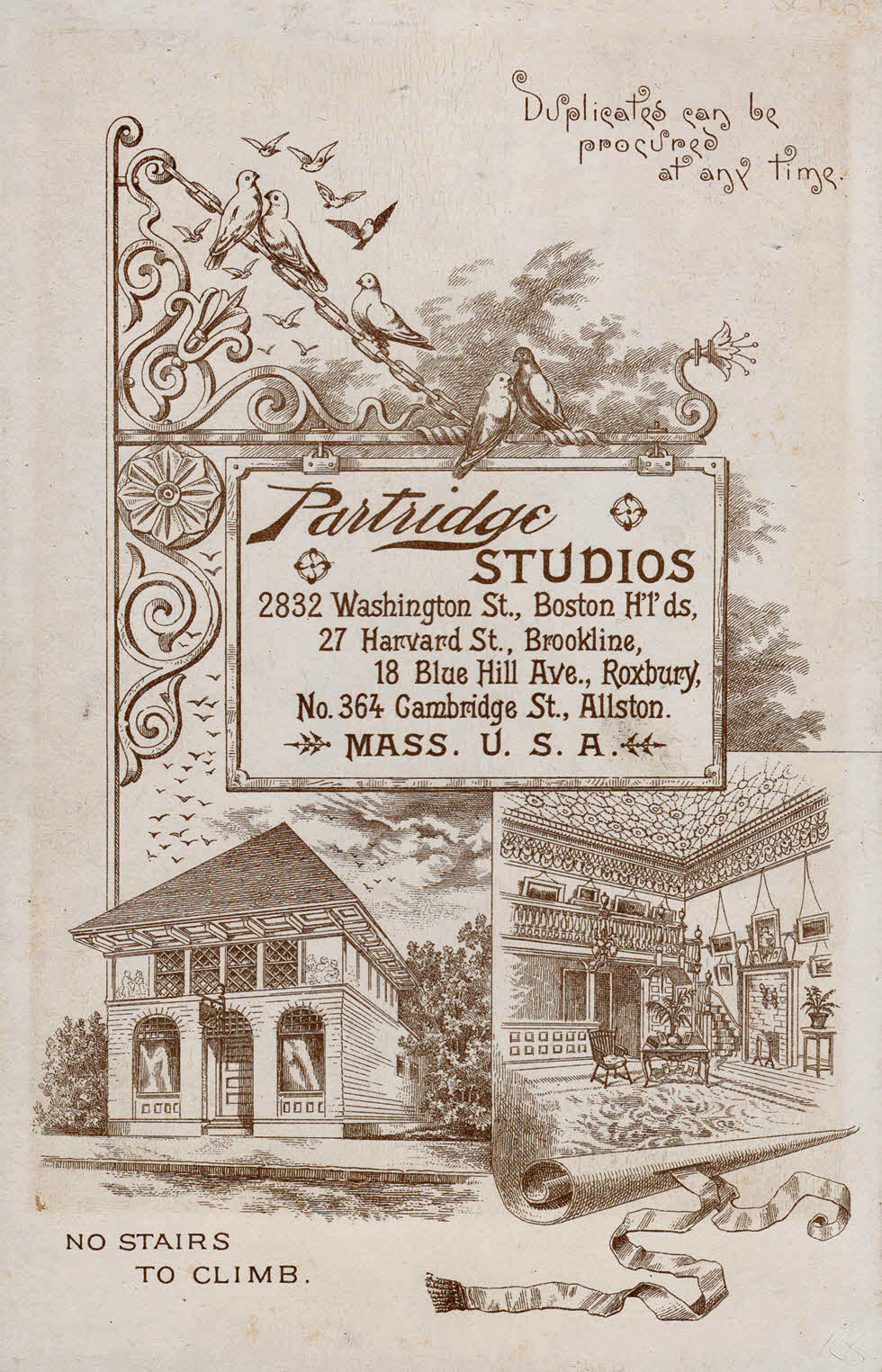

(7) William Henry Partridge eventually had eight locations of photographic studios in the Boston area. The jewel-box building at 2832 Washington Street in Boston is shown with its high-ceilinged parlor studio – along with the promise: “no stairs to climb.”

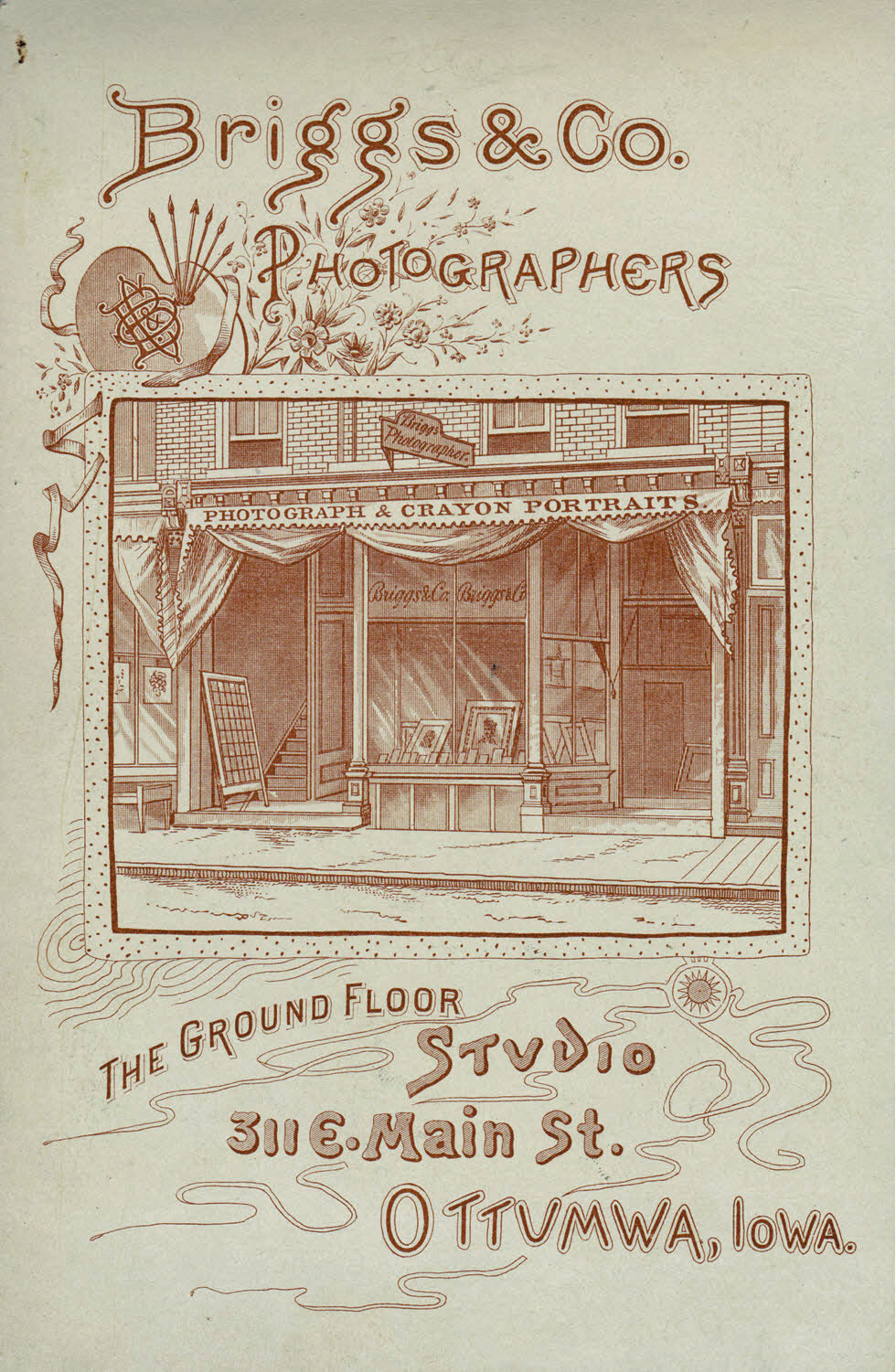

(8) Frederick Leonard Briggs in 1880 lived in a modest Ottumwa Iowa boarding house but had begun his photography business. He operated first at 227 Main Street but moved to larger premises at 311 East Main, where he had “The Ground Floor Studio” with large show windows on the street. He even leaned a sample board of his work in the alcove to stairs leading to the upper floors. A two-sided V-sign was mounted on the facade of the building, “Photograph & Crayon Portraits” printed on the edge of the awning, and his name repeated on the show windows.

Horse Trading in New Hampshire 1824

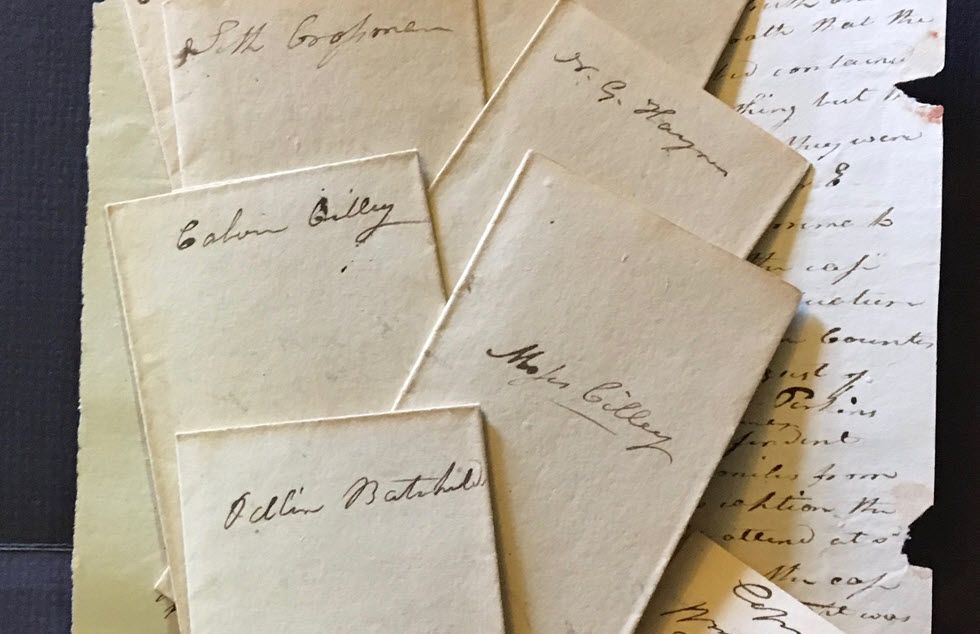

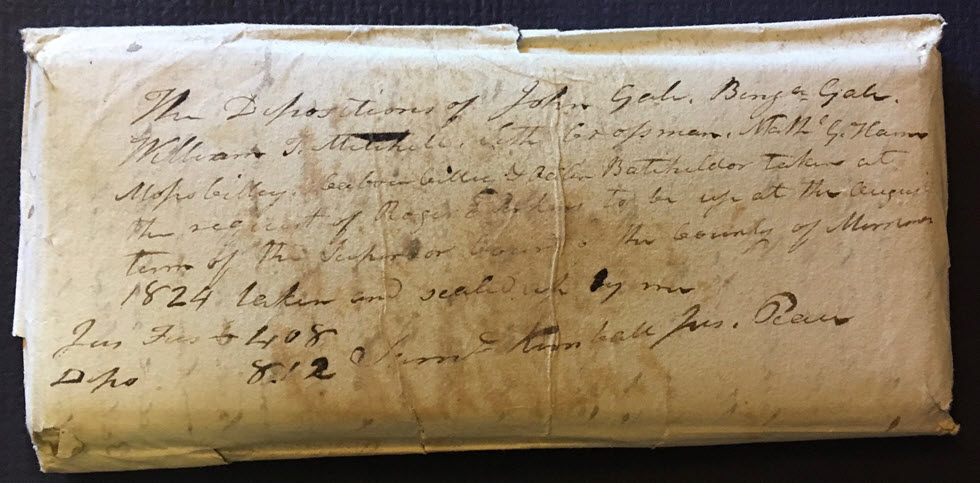

A sealed packet of depositions taken at Andover, New Hampshire July 17, 1824, unfolded one of those narratives that was differently ‘colored’ for each correspondent. (Illustrations 1 and 2)

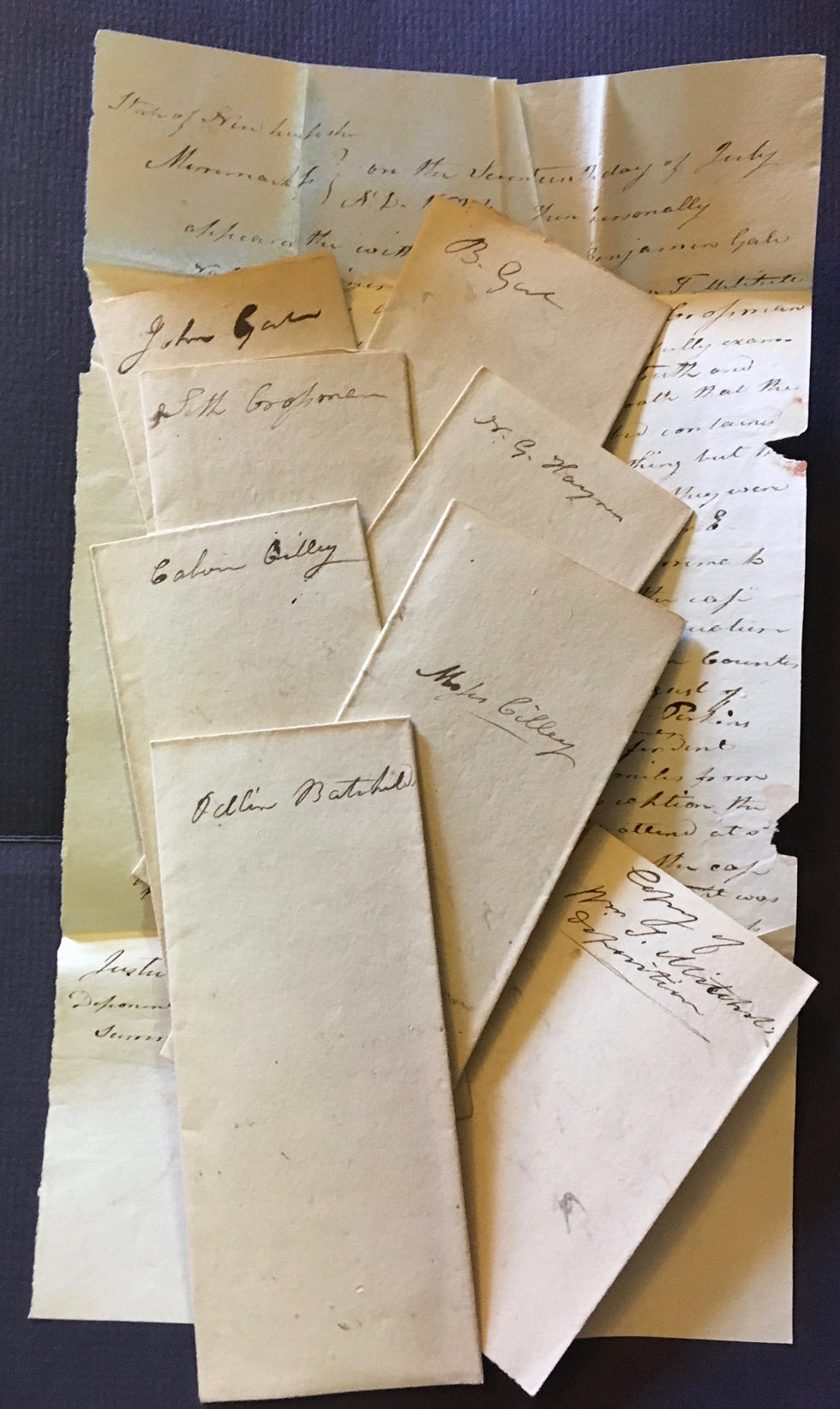

The Justice of the Peace, Samuel Kimball, had subpoenaed eight men to appear in Andover – all living more than ten miles from Concord, the Merrimack county seat, where the trial was to be held the next month. The defendant, Joseph C. Thompson, was also present at the depositions. (Illustration 3)

Though the charge isn’t revealed, it is clear that the plaintiff, Roger E. Perkins, believed that the defendant had sold a horse of his too cheaply.

The eight men all agreed that the sale had been in the summer (most said August) 1823. Six had been at the auction called by Joseph C. Thompson, and the same six agreed that a colt belonging to the plaintiff had been sold to Benjamin Thompson for $49 (one said “a little short of fifty dollars”).

Five of the witnesses said that the auctioneer arranged for his father to put in the winning bid – William Mitchell, a young boy who had caught Perkins’ colt to bring him in to auction, had even been sent for the father to instruct him to bid. All agreed that the son promised to buy the colt after the sale, if his father was “sick” of the “bargain.” The consensus was that the colt was worth more, but not that Joseph Thompson acted improperly. Seth Crossman observed that he had sold property as a Deputy Sheriff and that Thompson had kept the bidding going longer than he would have. Nathaniel Haines believed the colt was worth $100, Calvin Cilley guessed $80.

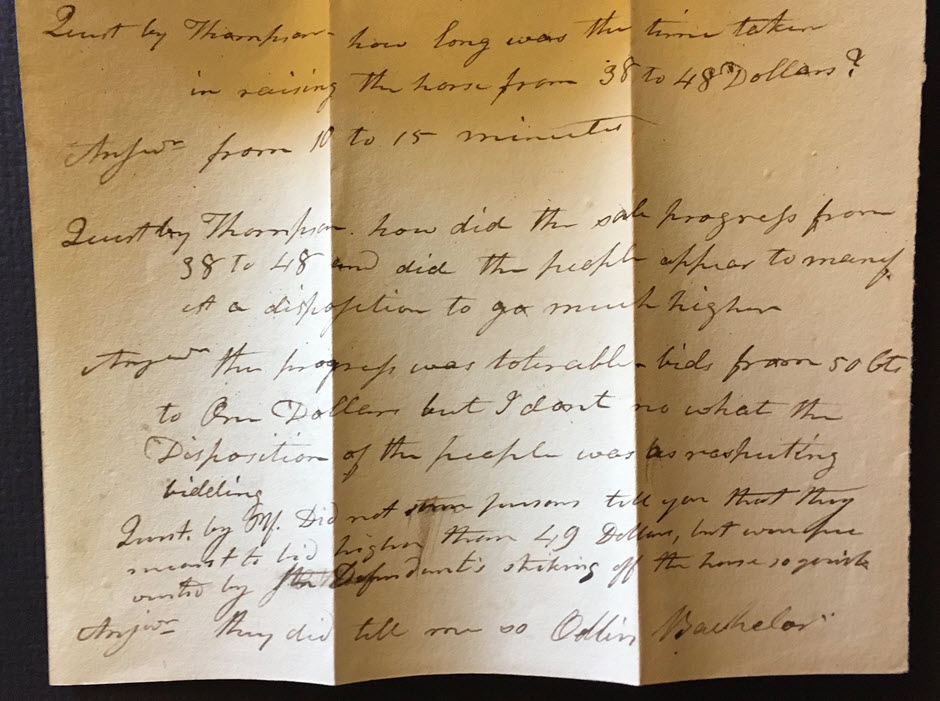

Odlin Batchelder swore that it took 45 minutes to sell the colt, and that to get to the final bid from $38 took from 10 to 15 minutes. He added that a hail storm occurred after the $38 mark. His testimony was the only one questioned by the defendant – who asked that the J.P. add the remark that he thought Batchelder “was too much intoxicated” to be a reliable witness. (Illustration 4)

John Gale revealed a complication: in 1822 Thompson had had instructions to attach some of Perkins property to satisfy a claim of a Mr. Stinson, and Gale was privy to a conversation where Perkins asked for more time to get advice from his attorney. Then, in the summer of 1823, Perkins’ colts escaped and Gale rounded them up into his pasture. Thompson was afraid that this was a ploy to put these assets out of the county. Gale testified that that was unlikely. Moses Cilley testified that he was instructed by Thompson to find where Perkins’ colts had been pastured, round them up, and take them to Joseph’s brother Herod Thompson’s stable. And then the auction.

Looking to outside sources reveals some of the role of taverns in these men’s lives. The depositions were taken in Andover at a tavern owned by the J.P., Samuel Kimball. The critical auction was held at the Auburn tavern owned by the defendant. Two of the witnesses, Seth Crossman and Nathaniel Haines, owned taverns in the Andover area – John Gale’s testimony was about events at the Crossman tavern. The plaintiff, Roger Perkins, owned the Babson tavern in Hopkinton (about 25 miles from Andover and closer to Concord), run by his brother Bimsley Perkins.

Was $49 for an (apparently) untrained colt a bargain? $49 in 1824 is about $1500 in today’s dollars. And, today, in upstate New York, I would have my choice of several thoroughbred, fully trained yet young, horses for that price. In 1824, $49 was the average annual wage for a domestic servant in New England; or would have bought passage on a ship to England.

Clearly, all parties involved in this court case believed the colt to be worthy. You be a judge: would you award damages to Perkins?

Happy Ruby Anniversary

1980 to 2020

Ruby-red is a color at the end of the color spectrum (next to orange): the color of rubies or blood or cherries.

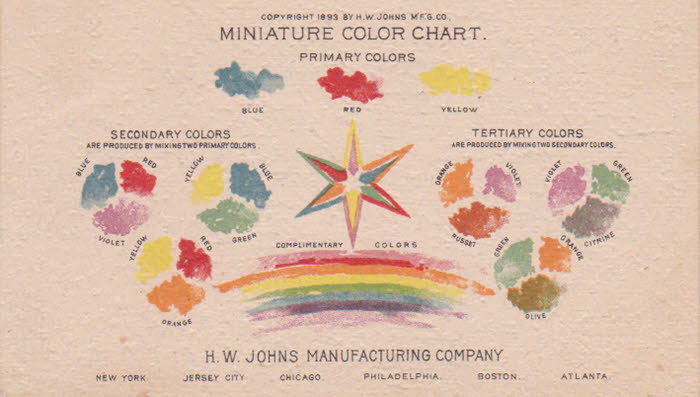

1893 trade card for H.W. Johns paint

Red of all hues is a signature color for a wide range of ephemera.

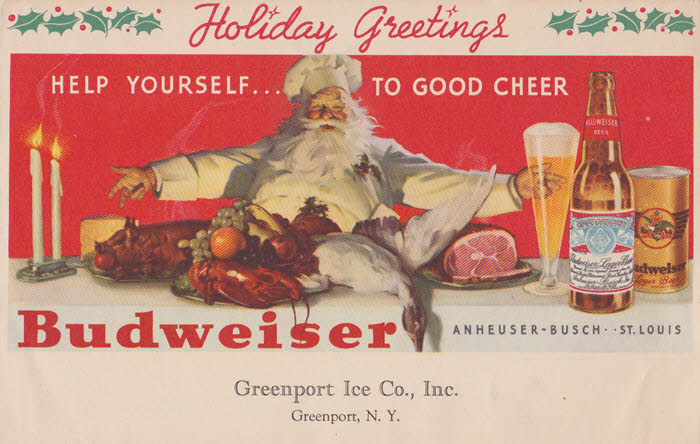

Red is the color of Santa Claus (thank you Thomas Nast) and there-fore of Christmas.

1938 advertising mailer for Budweiser beer

And has been Coca Cola’s signature since the 19th century.

1930s folder for ice-cold Coca Cola in Germany

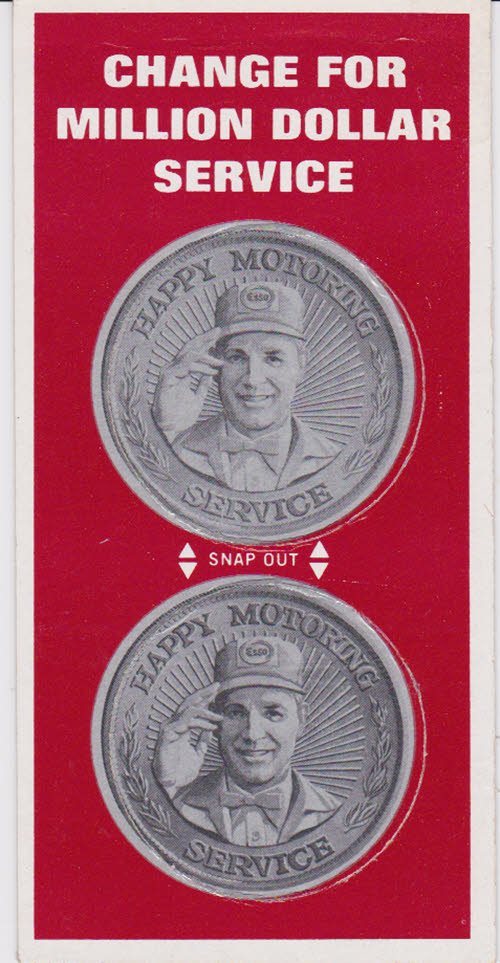

Red is the trademark color for businesses such as Esso (now Exxon).

Advertising tokens from Esso in the 1950s

Cornell is just one of the universities known for its Crimson.

Ribbon (“Egyptienne Luxury” “Factory no.7 3rd District State NY”)

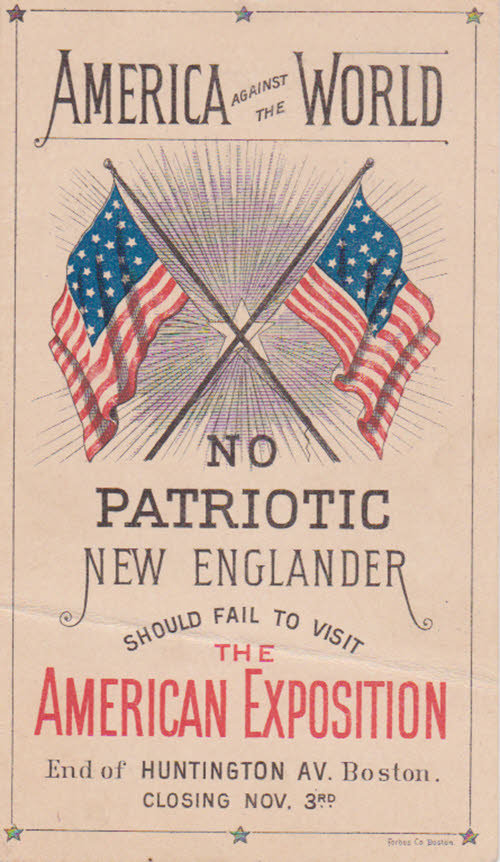

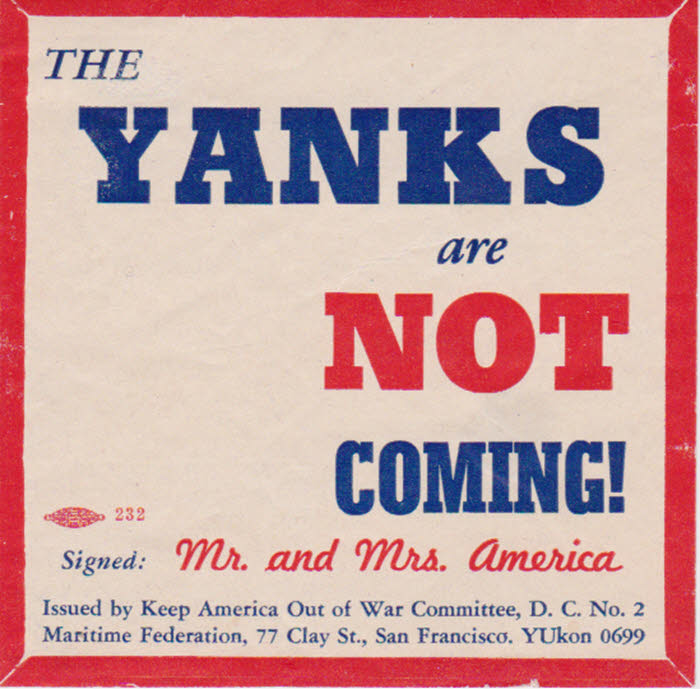

Red accompanies blue in patriotic & political ephemera.

1884 advertising card for a Boston exposition (Forbes Co.)

1940 gummed anti-war label

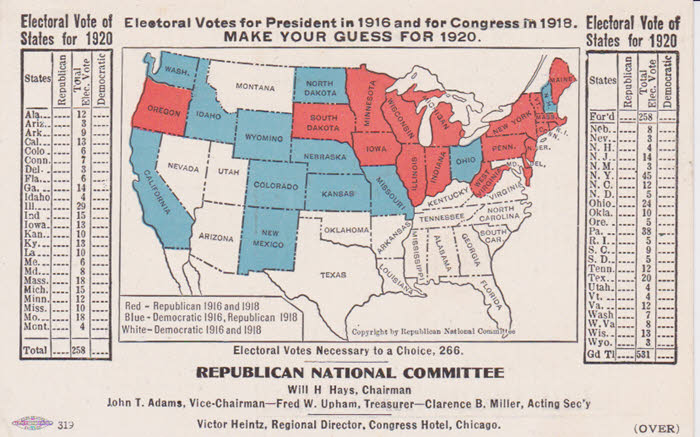

1920 election predicting card

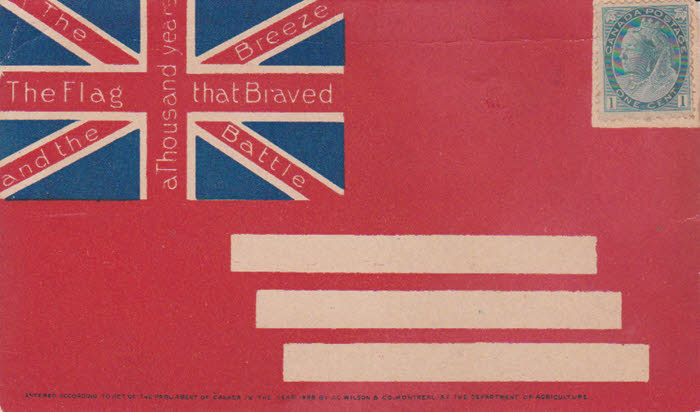

1898 pre-stamped card advertising a Montreal hotel while extolling the Royal Red En-sign, the country’s unofficial flag before 1965

Red as a particular color appears in advertising for paint.

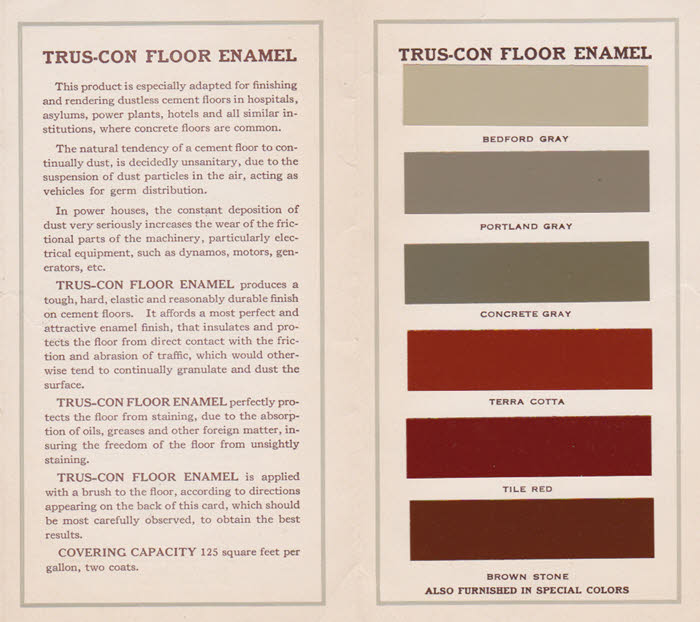

1920s folder with paint chips (“Tile Red”) for Trus-Con Laboratories, Detroit

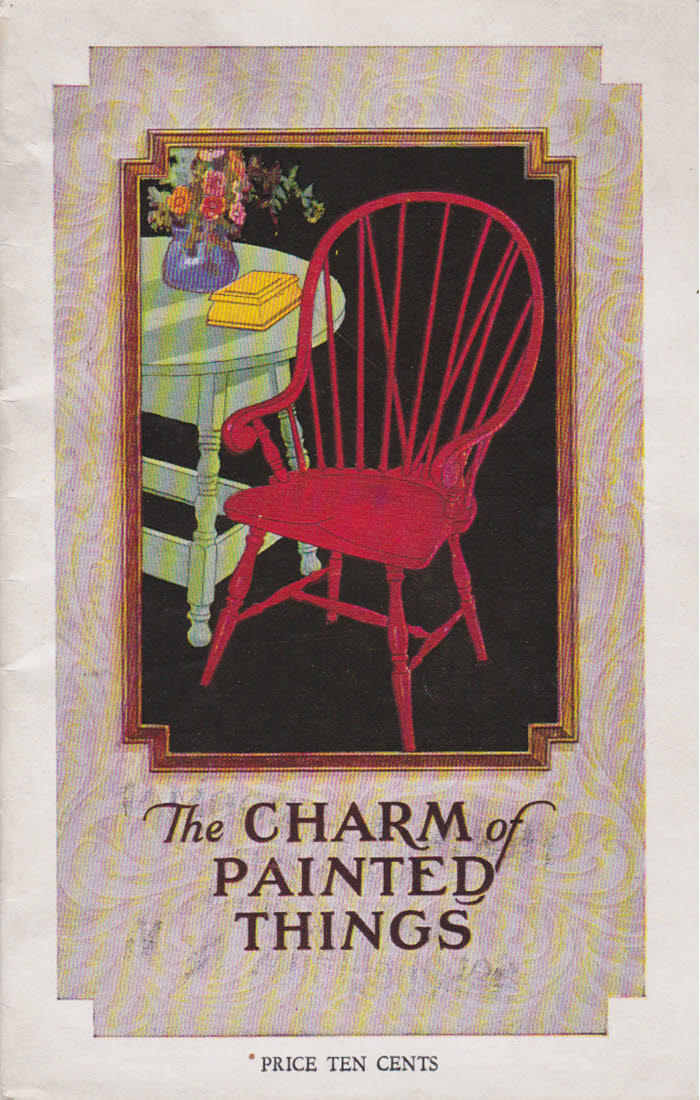

1928 Boston Varnish Co. booklet promoting the painting of old furniture (“Rich Red”)

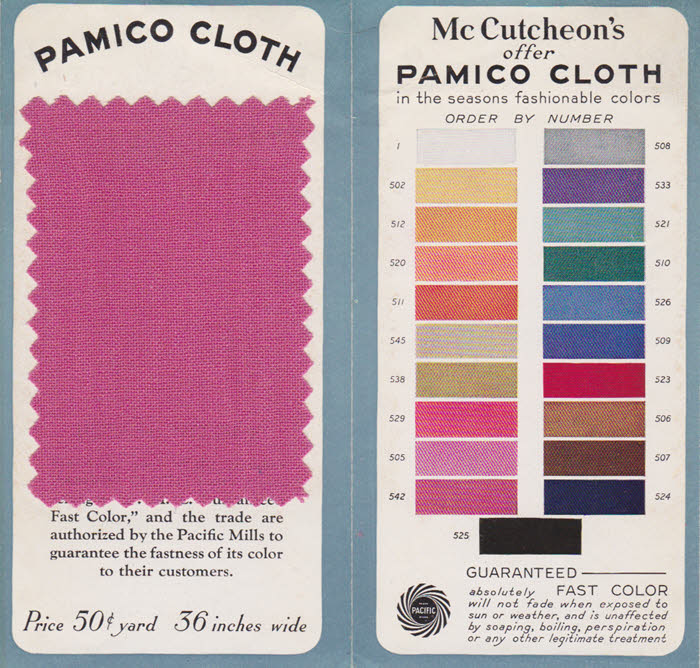

Red as a dye is promoted for fabric.

1920s fabric swatches for Pacific Mill Pamico Cloth (Red “523”)

1941 flyer for Camel Spun jackets, by Philip of Chicago (“Stop Red” for women)

Red crayon is a must for advertising coloring books.

1920s Crayola drawing book, Binney & Smith Co.

1925 Genuine Drawing Book by the Regensteiner Corp (Colortype)

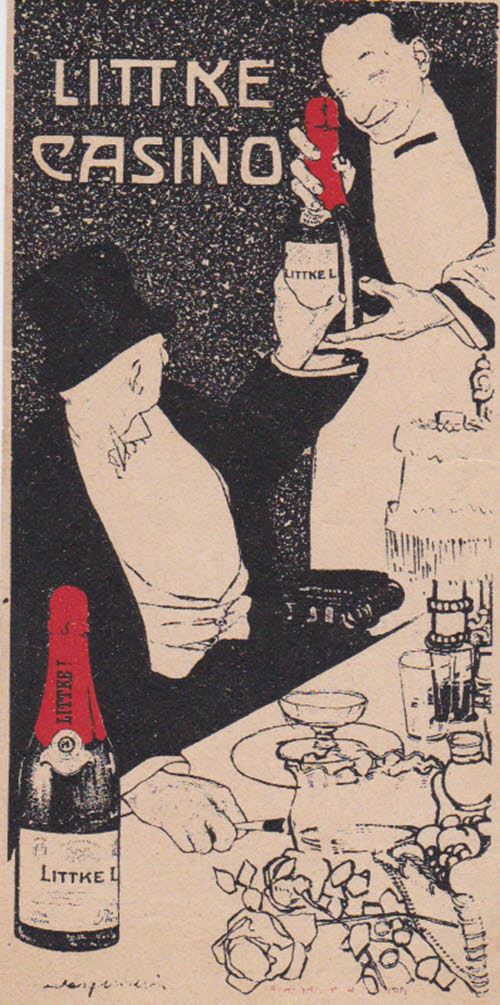

In Hungarian cafés in the 1930s, waiters tallied on advertising chits: printed on inexpensive paper, most used red as an eye-catching detail.

Littke L sparkling wine

Meinl coffee (artist Bakács)

Nikotex cigarettes (artist Bereczky)

Red is hard to ignore.

Luggage label to promote the Belgian airline Sabina 1920s route to Paris

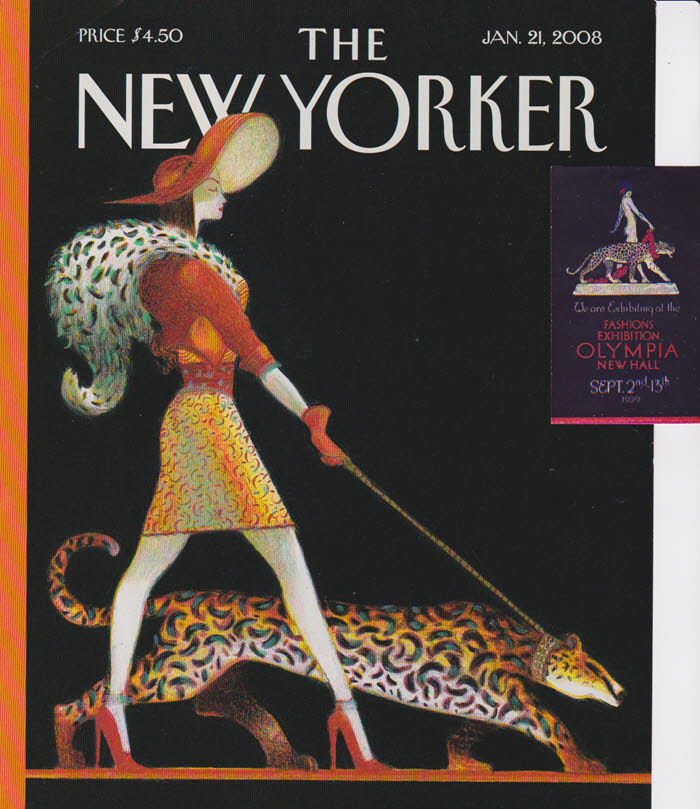

Red highlights timeless design: a 1929 poster stamp inspires a 2008 magazine cover.

Off the Cuff

Did you know that the expression came from nineteenth-century politicians (and others) cribbing from notes written on their paper cuffs?

Apparently the urge to avoid washing the white collars and cuffs that were a hallmark of Middle Class employment or womanly gentility was strong enough to create a decades-long industry in substitutions for cloth.

Paper was the first choice – and the first paper collars appeared in the 1850s under the name “Persigny” for the French Minister of the Interior. Here a pasteboard box with a view of the Capitol in Washington on the lid held a dozen “Congress Paper Collars.”

A similar pasteboard box held a dozen crimped paper ruffles – each long enough to edge the neckline of a woman’s bodice or cut in half to edge cuffs. The patriotic emblem on the lid implies this appeared during the 1860s.

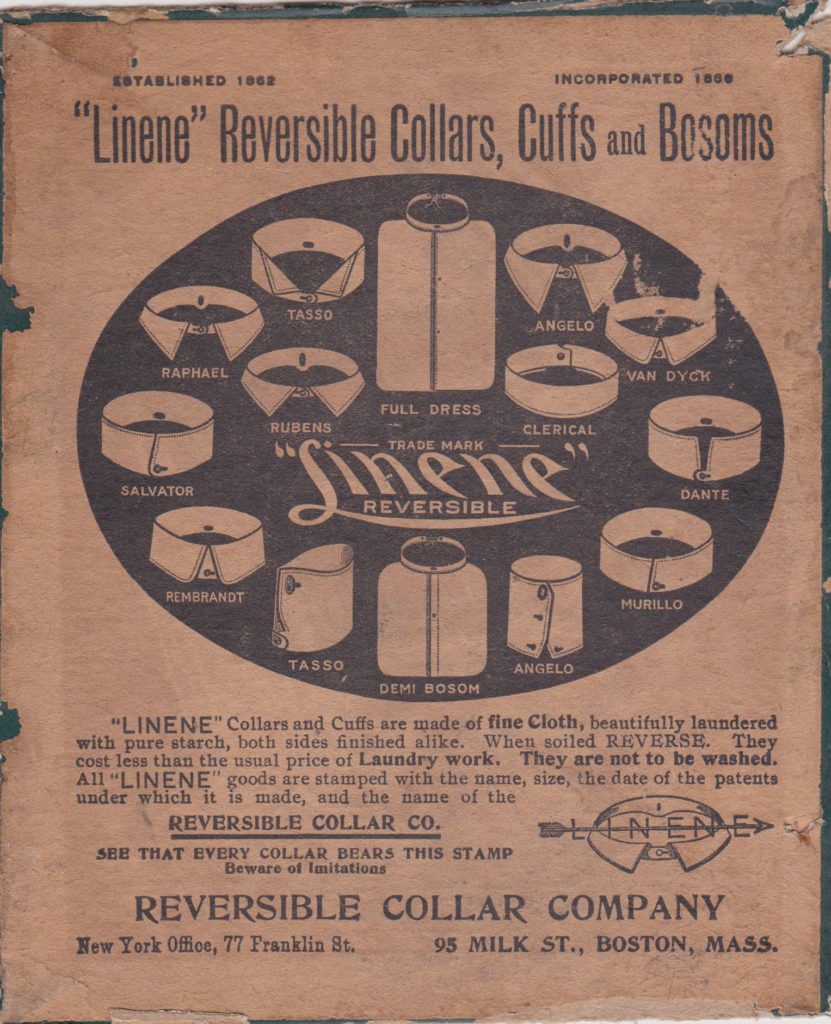

But treated paper mixed with cloth fibers was an even better idea – “Linene” was invented in Boston by George K. Snow in 1866, who packaged his collars and cuffs around the turn of the nineteenth-century in a box with this lid advertisement illustrating the different styles.

The actual collar, from the 1920s, is a 14.2 inch “Marvin” style, manufactured under the name “Launderno,” trademarked in 1917 for resin-impregnated linen that would never need laundering.

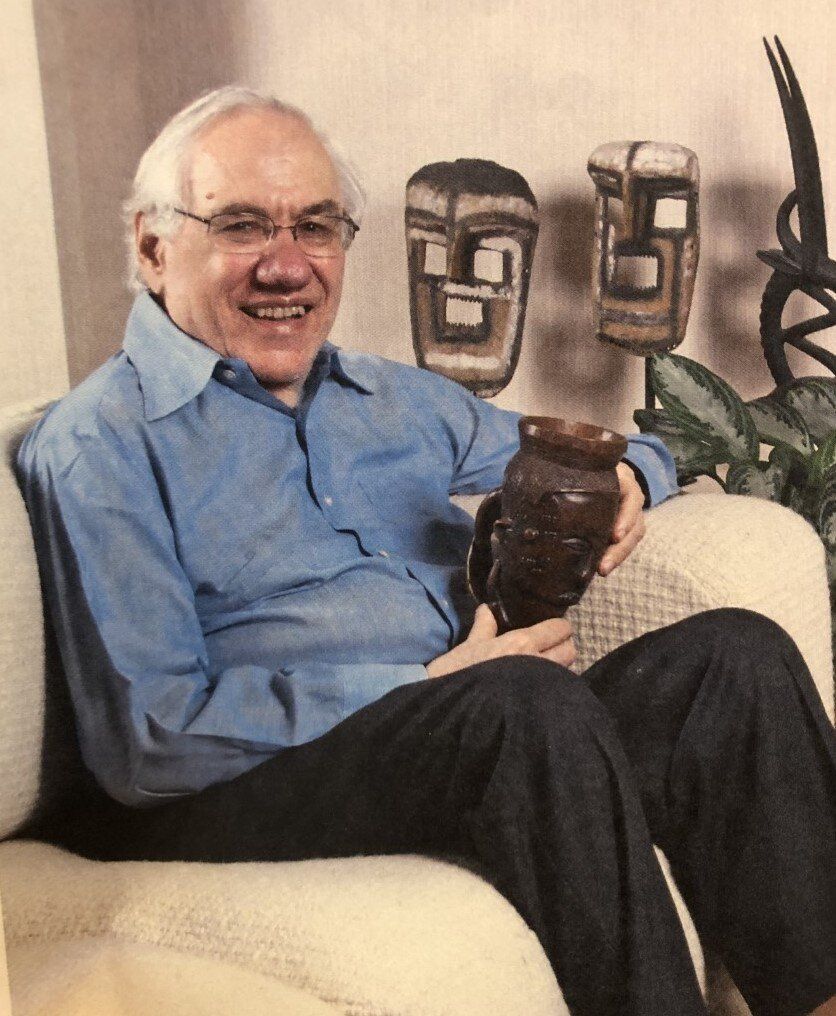

About the author . . .

Diane is partners in aGatherin’ – dealers in ephemera since 1979. She is the editor of publications for both the Ephemera and the Postal History Society. With partner Robert Dalton Harris she was awarded the Maurice Rickards Medal for excellence in the field of ephemera in 2008, and the Luff Award for Distinguished Philatelic Research in 2016. She has given presentations and workshops on Victorian dress and customs at Lake Mohonk Mountain House, including an annual workshop to create Victorian Christmas ornaments for their parlor tree.

Cash Railways

Some stores still use them: a rubber-footed canister that speeds through a maze of tubing via compressed air, delivering receipts and change with a satisfying ‘thonk.’ At one point, most of the major cities of Europe and America even had such pneumatic tube service integrated with the postal system.

But, for communication of objects within stores or businesses, there were other mechanical options, given the generic term of “cash railway.” William Stickney Lamson of Lowell, Massachusetts, patented a ball system in 1881 that protected the ‘cargo’ in a hinged wooden ball that ran along sloping wood and leather rails, propelled by gravity. He formed the Lamson Cash Carrier Company in Boston in 1882 and went on to manufacture a system where the ‘cargo’ was placed in a carriage suspended on pulleys from wires. Lamson called this the “Level Wire System” but others were named “Rapid Wire” or “Air-Line.” His company became The Lamson Consolidated Store Service Company and branched out into Europe. In 1884, Lamson licensed the rights to his devices for the ‘Eastern Hemisphere’ to J. M. Kelly of England. By 1889, the London branch alone had installed 3,725 systems.

Lamson, born in 1845 and a Civil War veteran, opened a “five and dime” called the Rachet Store in Lowell where he first experimented with streamlining the cash transfer process. Company lore has him wadding up money in a handkerchief and tossing it, then encasing it in hollowed-out cricket balls and throwing them. Rolling the balls along elevated tracks was the first successful system (still operating in some British shops). Lamson then licensed the wire and pulley device patented by David Brown of Lebanon, New Jersey. The wire system could be enlarged to accommodate packages.

Three trade cards from the 1880s, issued by Lamson Store Service Co., provide the prices for the “Level Wire System” the “Ball System” and the “Bundle System.” The company would build everything needed, including a desk, or desks that would become the property of the merchant. But the systems themselves were leased.

The Ball System charges were by the number of stations; the minimum was assumed to be 4 and the rent $125 for the first year and $72 the second. Adding another station cost $10 the first year. A system of 25 stations was $450 the first year. Among the 44 businesses listed, of among the “seven hundred prominent business houses in the United States using the Ball System” are Lord & Taylor in New York and Newman & Levinson in San Francisco.

The Level Wire System was charged by numbers of ‘cars’ – the minimum being one car for $25 a year, and 4 cars or over at $10 each per year. 32 merchants are listed and over 150 others claimed – most in New England including the 3 stores of the Massachusetts Boot and Shoe Company.

The “Bundle System” cost $24 per station per year, and 25 lessees of the Parcel Carrier are listed including Sanger Brothers in Dallas and Hamburger & Company in Los Angeles – 75 others are claimed.

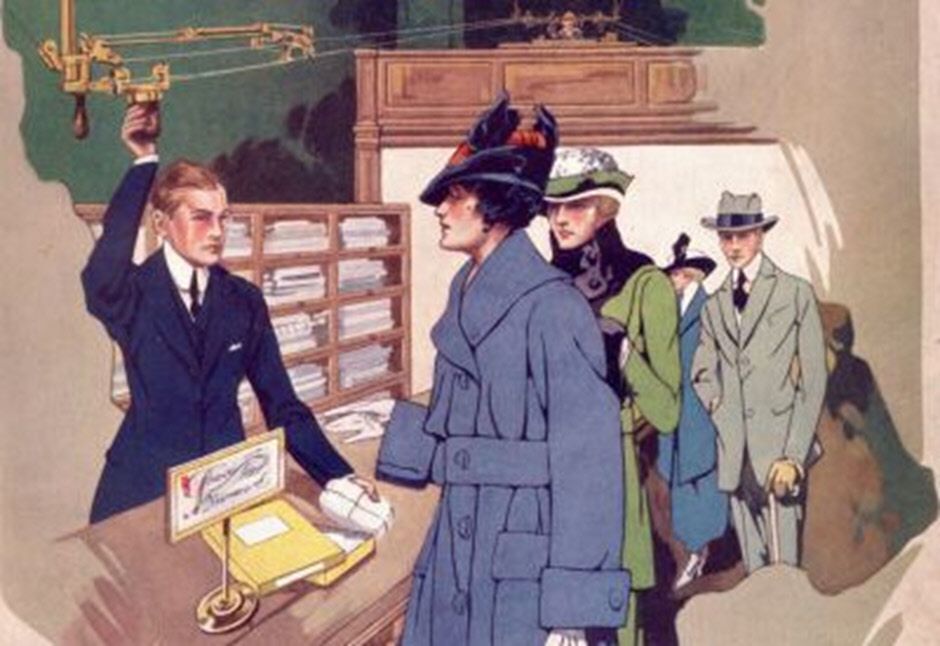

Illustrated here is the cover to the 1917 trade catalog, showing the wire system patented in 1892. The salesperson has placed the customer’s money in the wooden cup attached to the trolley on the wire. He would then pull the handle at left to release a catapult spring to launch the trolley on its way.

In the 1960s Diebold purchased the Lamson Corp. – they make ATMs. The English company still exists and makes pneumatic cash carrier systems.

(This article first appeared in Book Source Magazine.)

Swiss Communications Calculation

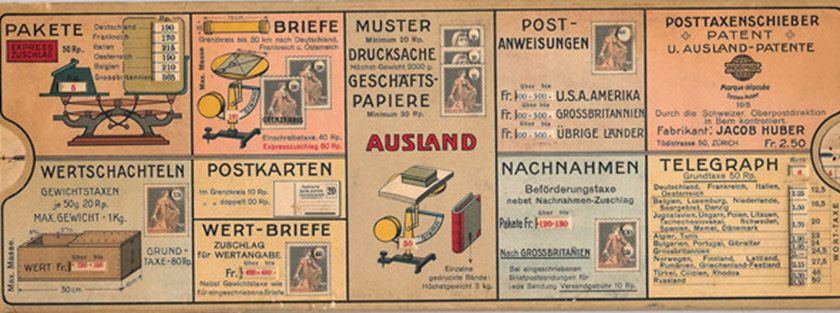

On the eve of the Great War, in 1914, a clever Swiss businessman invented and manufactured a “Posttaxenschieber” — an ingenious sliding scale that could calculate the cost of every form of communication available. The device was patented, was available at Huber’s shop on Tödistrasse in Zurich, and cost two and a half Swiss francs. The franc was similar to our dollar and was divided into 100 rappen, or centimes.

On one side, the scale covered the information for internal use in Switzerland. The ten illustrated panels showed, in the little square openings, what you would have to pay to: send a heavy express package, a lighter parcel, an ordinary letter, an express letter, a postcard, a money order, and insurance on any of the above. The postage stamps pictured were from two series. One, first appearing in 1907 but current until 1925 included the image of William Tell’s son with his crossbow for a small denomination, and the female warrior Helvetia with her sword for higher denominations. The second series had just been introduced in 1914 and showed the head of William Tell.

The calculator also showed (two panels on the right) how much a telegram would cost (60 rappen fee plus words at 5 rappen each, or 110 rappen for a 10-word telegram). And how much a telephone call would cost — a minimum of 10 rappen for 3 minutes. The fact that postal rates appeared together with these electric communicators distinguishes Switzerland (and, indeed, the rest of European countries) from the United States where, despite decades of discussion beginning in the 1840s, the Post Office Department failed to get Congressional approval for absorbing the telegraph. Only in America were electromagnetic communications solidly (and still) in the hands of private enterprise.

On the other side of the calculator are the various rates for foreign communications. Again, prices are shown for different classes of packages, and letter mail, and postcards. For France, Austria, and Germany it is pointed out that, because of the pneumatic tubes, there is a diameter limit to mail of 10 centimeters. In addition to mail, you could send a telegram to Great Britain, but not to the United States (presumably, you could direct onward transmission via cable from one of the intermediate places).

Significantly, there is no long-distance telephone — as there was not, really, in the United States. Although there was a line connecting New York and Chicago in 1892, and then to Denver in 1911, ordinary citizens did not avail themselves of a very costly service that kept snagging on the limits of sound transmitting technology. Finally, in 1914 a transcontinental telephone call was possible but was not accomplished until Alexander Graham Bell ceremoniously placed the first call from New York to San Francisco in January 1915. That first call involved several operators and took almost a half-hour to connect — but those of us old enough to remember service just post World War II know that long-distance calls remained expensive and exotic for a long time.