Architecture and the Photo Studio

The expanding popularity of inexpensive photographic portraits of the “cabinet” size (4.25 x 6.5 inches) in the 1880s and 1890s increased competition among photographers. The printed backs of the portrait card offered a prime venue for advertising; not just text but often an architectural rendering of the photographer’s studio. For us it is an opportunity to examine alterations to a building to improve photographing conditions, and to note signage and other promotions.

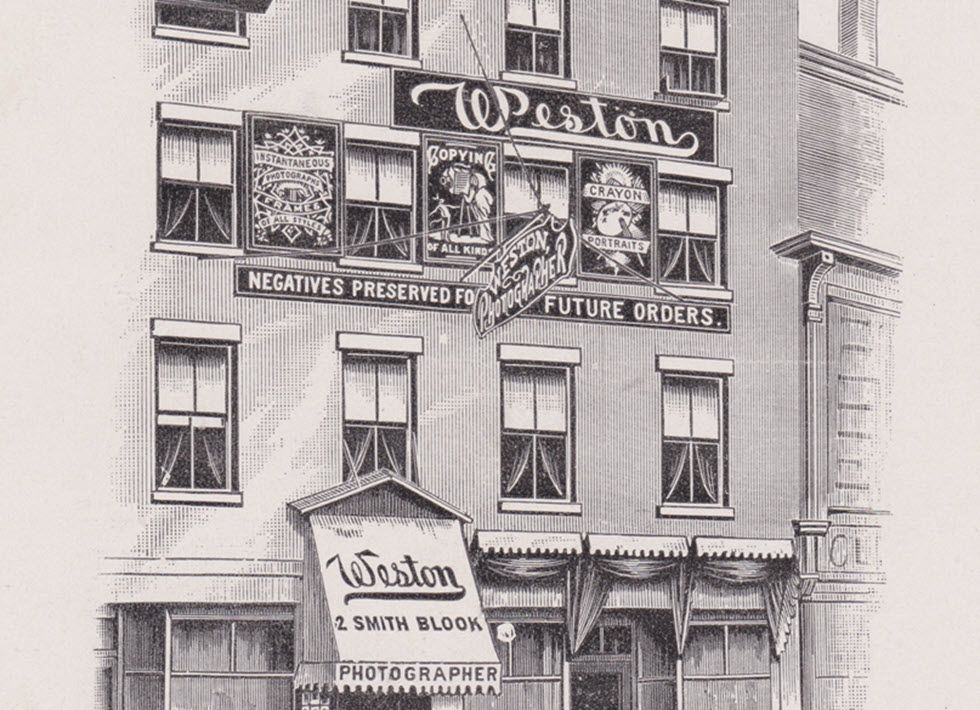

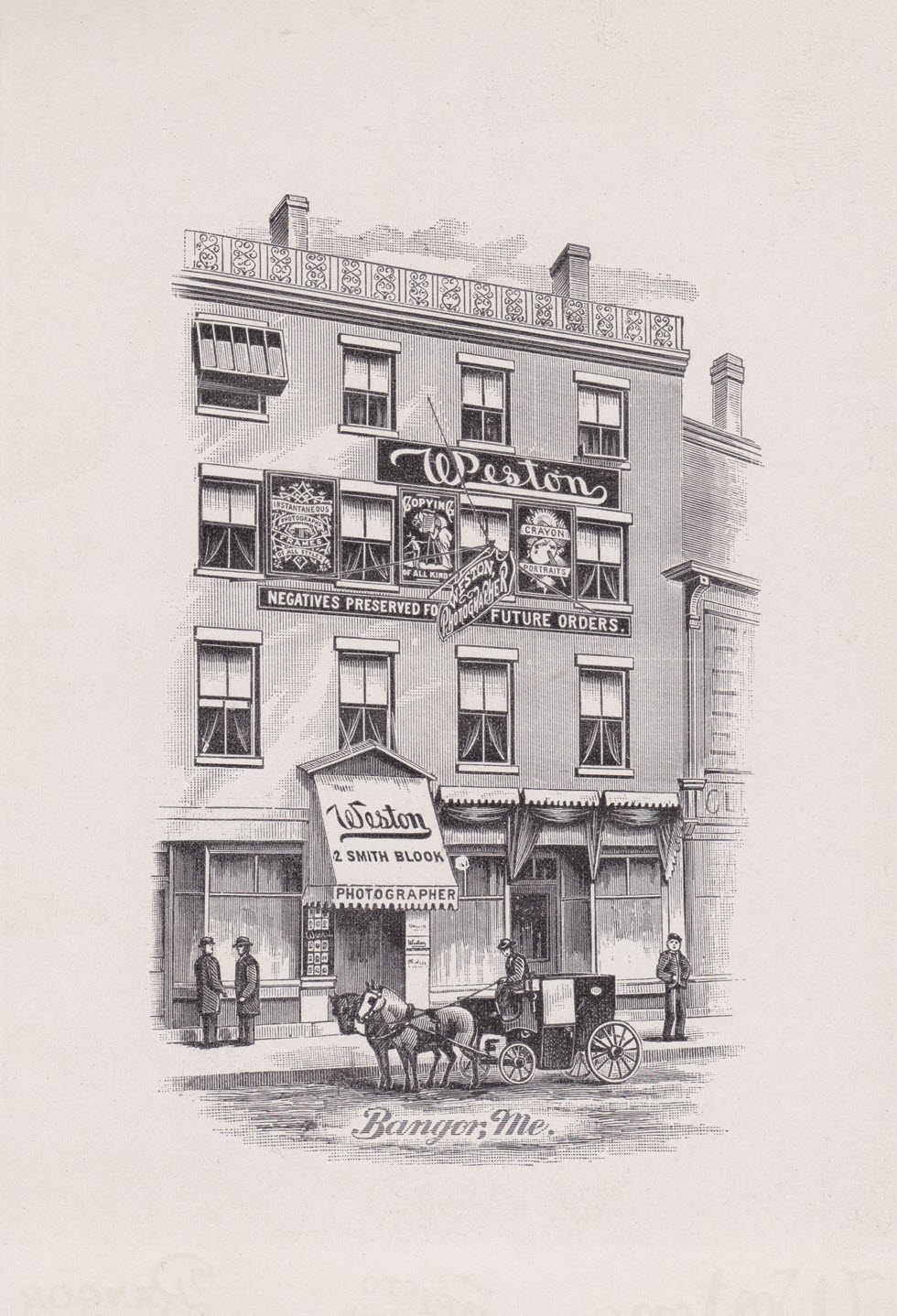

(1) Frank C. Weston of Bangor, Maine established his studio on the upper two floors of the Smith Block. To make sure that prospective clients knew the exact location, he had mounted a large sign between the third and fourth floor facades, and a swing sign pendant from the center of four windows on each of those floors. Between the windows of the third floor he mounted illustrated “poster” signs that detailed his specialties: “Instantaneous photographs; frames of all styles” “Copying of all kinds” “Crayon portraits.” Despite other merchants occupying the other two floors, Weston had his name on the front door awning and a case of portrait examples on display to the left of the door. Photographers needed as much natural light as possible, and curious protrusions from two of the fourth floor windows (especially the multi-paned box on the far left) were built to direct more light to the studio.

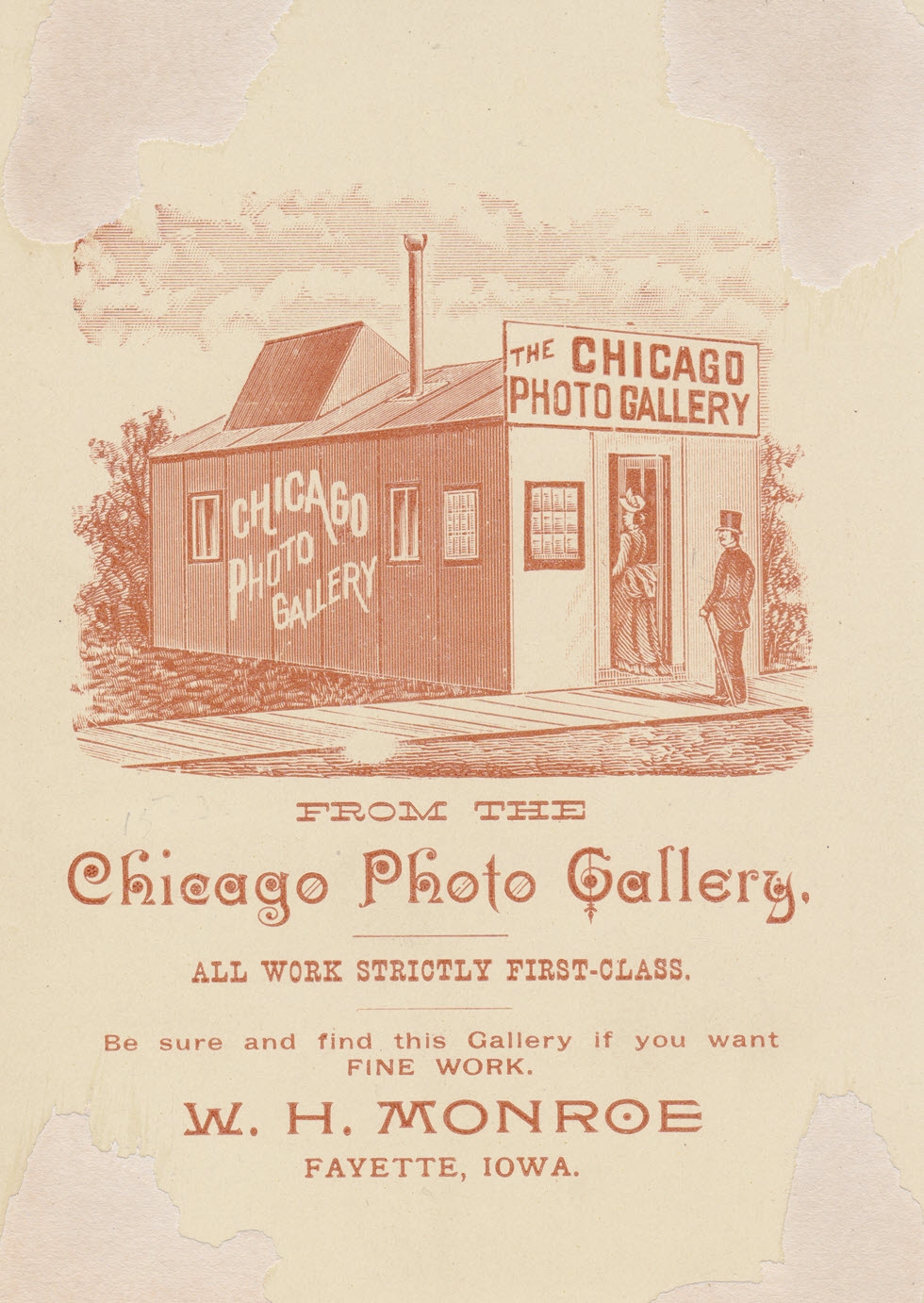

(2) Alterations to existing buildings for increasing light appear in many of the cabinet card backs. The least elaborate was made by W.H. Monroe to his modest metal photo shack, proudly delineated “The Chicago Photo Gallery” in tiny Fayette, Iowa. An angled sky light has been let into the rolled tin roof – the better to photograph fashionably dressed women and gentlemen, shown entering the gallery, having passed over the board sidewalk.

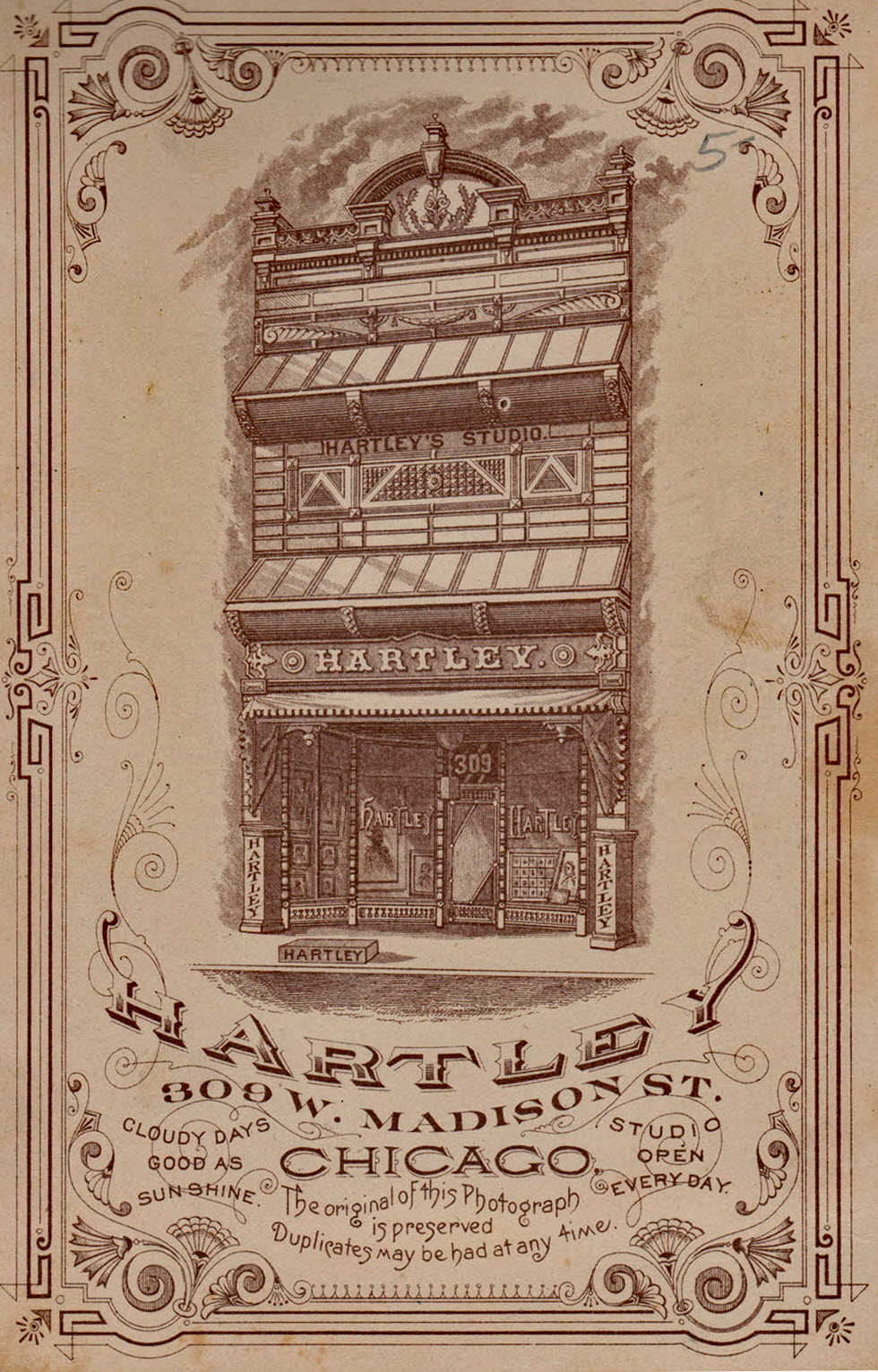

(3) In Chicago itself, Edward F. Hartley may have designed his three-story building at 309 West Madison specifically to light his photographs (made from 1875 to 1894). If he bought an existing structure, he certainly adapted it comprehensively: the windows on the second and third floors have been replaced by multi-pane ‘balconies’ of light scoops – allowing him to boast “cloudy days good as sunshine.” Harley placed his name in as many places on the building as possible: on the face between floors, on the sign above the entrance, on the curved glass of the lobby entrance, on the corner pillars and even on the mounting block on the sidewalk.

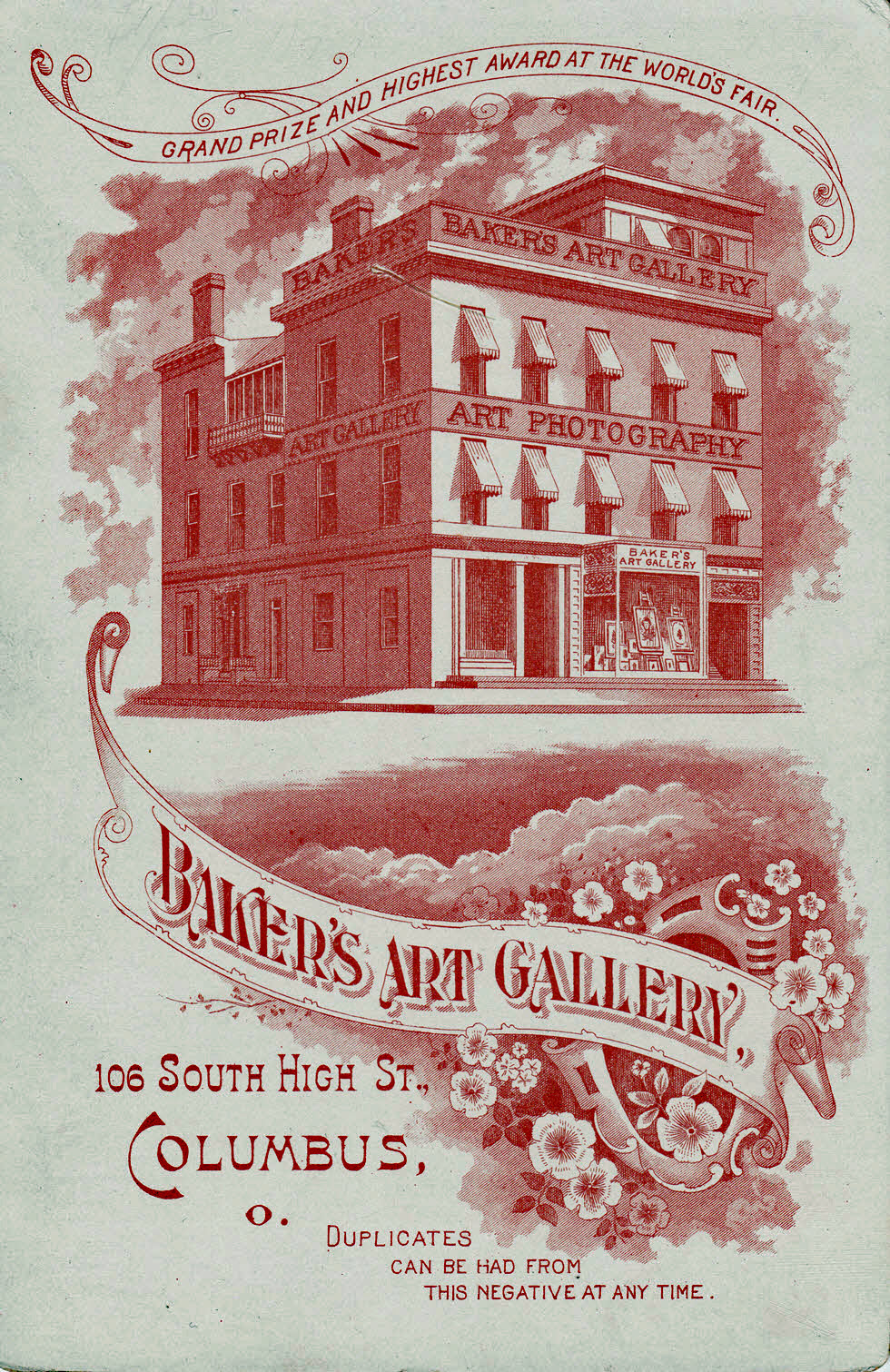

(4) In Columbus, Ohio Lorenzo Marvin Baker also chose a three-story building but on a corner, placing his “Art Gallery” and “Art Photography” on the top two floors, plus a penthouse. The top floor has a balcony with six tall windows that would provide more light, and the penthouse has slanted light reflectors. A photograph of the location around 1905 shows an even more elaborate light capturing structure built on top of the penthouse, and signs advertising the photography business filling in all the space between the windows on the second floor.

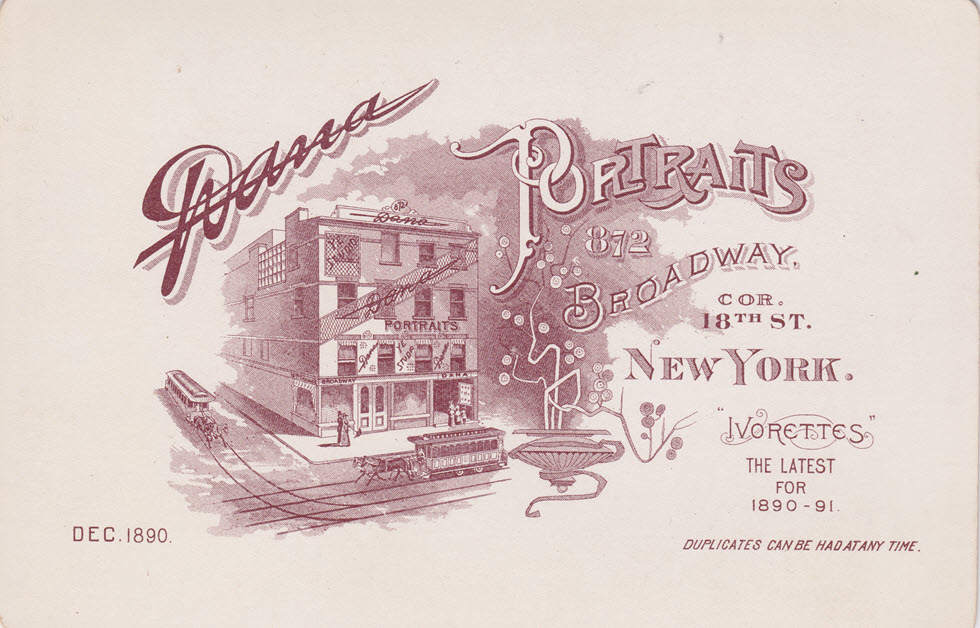

(5) One of the best known urban photographers, Edward Cary Dana established a four-story emporium at 872 Broadway – a corner building that he swathed in signs mounted on wire mesh. This was just one of eventually four studios – one that opened in Brooklyn in 1892 had a specially constructed 19 x 55 foot skylight with a west of north exposure. Here, in 1890 on the corner of 18th street, he has created an inset of 4 x 7 glass bricks for more light. To emphasize his artistic approach, this vignette is printed on the card back in landscape rather than portrait view.

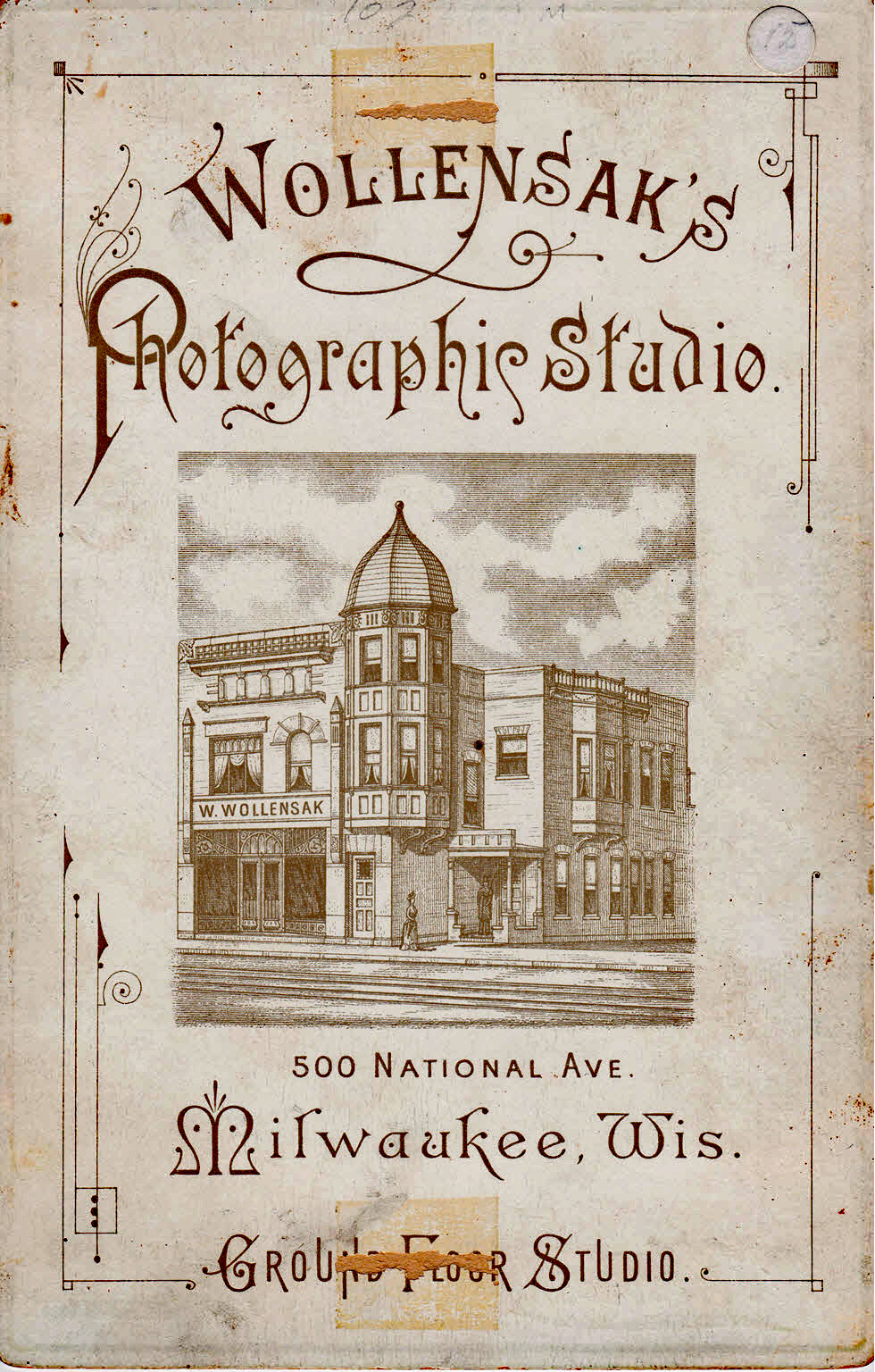

(6) Successful urban photographers could spread over more than one floor of a building. But several more modest establishments made a virtue of there being no stairs for clients to climb. William Wollensack’s studio at 500 National Avenue in Milwaukee was promoted as being on the ground floor.

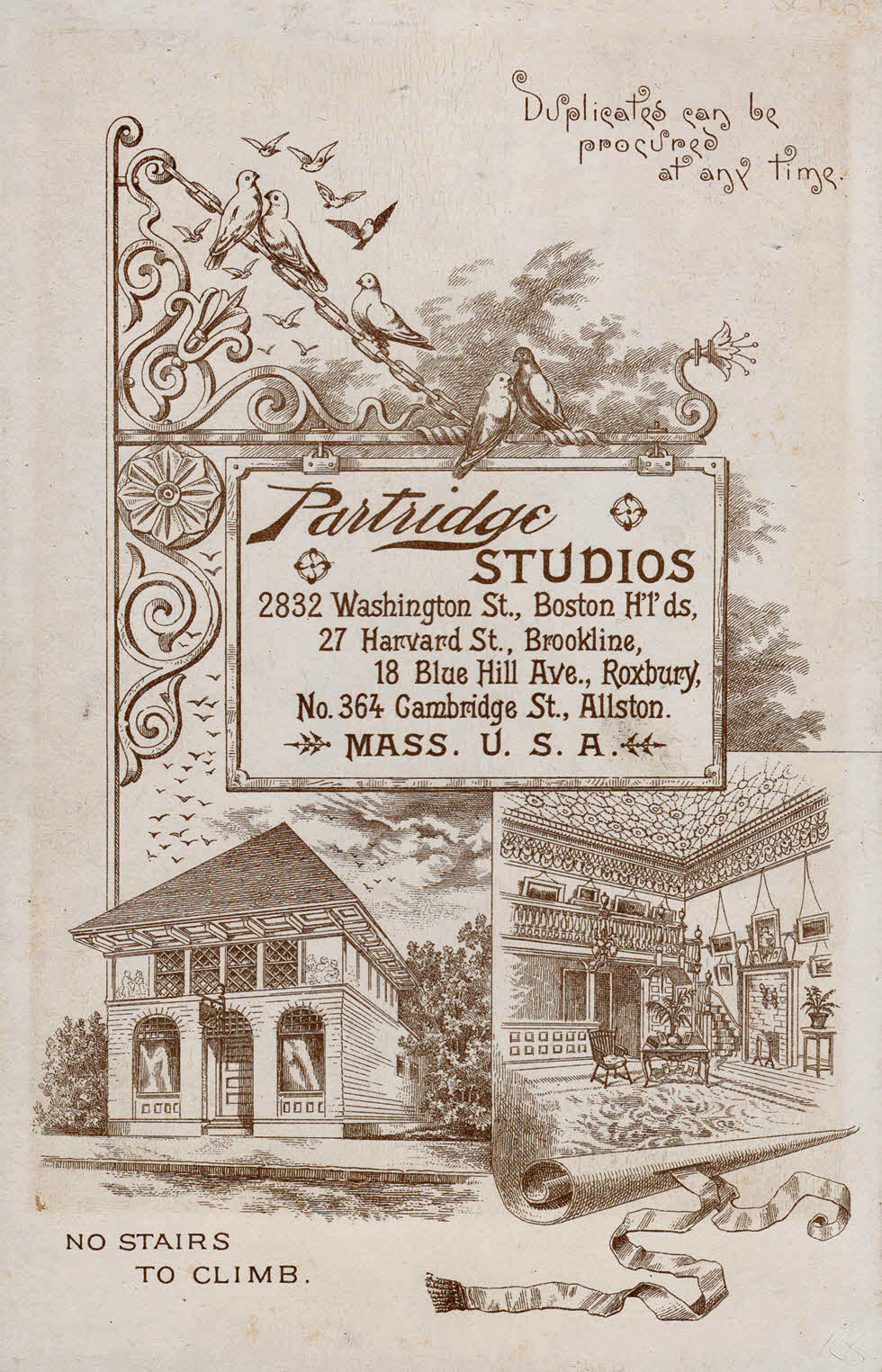

(7) William Henry Partridge eventually had eight locations of photographic studios in the Boston area. The jewel-box building at 2832 Washington Street in Boston is shown with its high-ceilinged parlor studio – along with the promise: “no stairs to climb.”

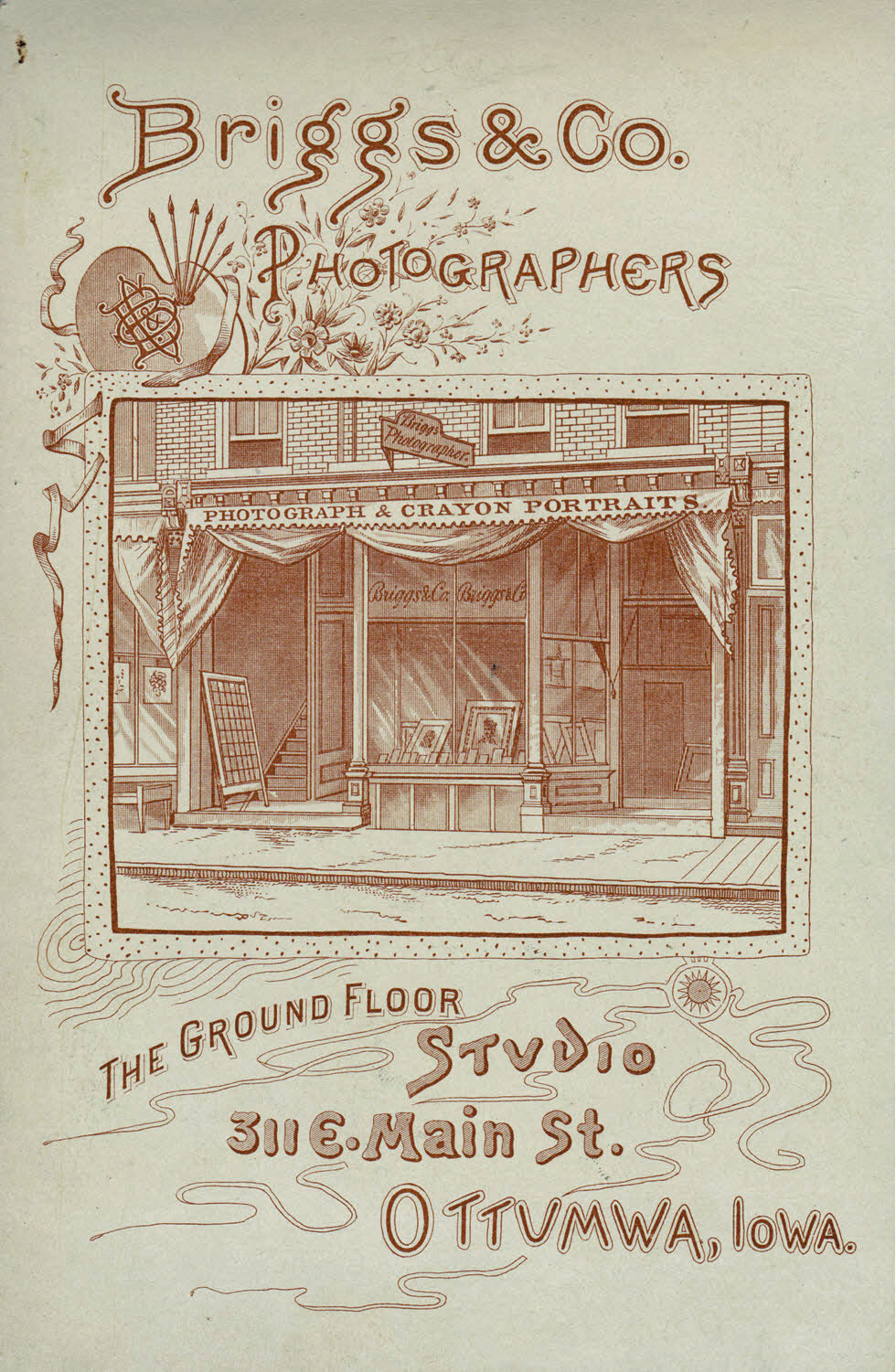

(8) Frederick Leonard Briggs in 1880 lived in a modest Ottumwa Iowa boarding house but had begun his photography business. He operated first at 227 Main Street but moved to larger premises at 311 East Main, where he had “The Ground Floor Studio” with large show windows on the street. He even leaned a sample board of his work in the alcove to stairs leading to the upper floors. A two-sided V-sign was mounted on the facade of the building, “Photograph & Crayon Portraits” printed on the edge of the awning, and his name repeated on the show windows.