Marbled Edge Continental Currency Challenged British Counterfeiting

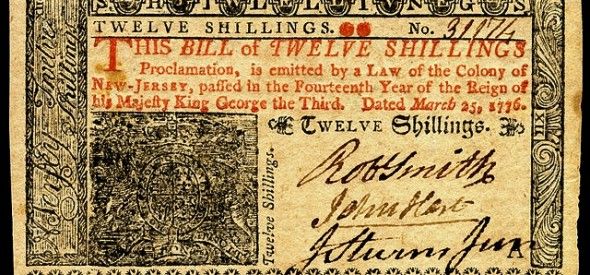

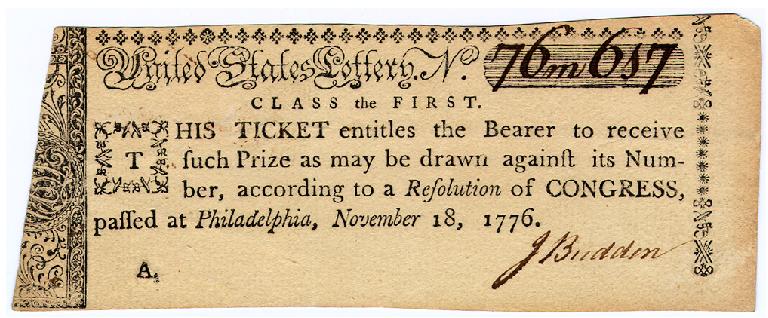

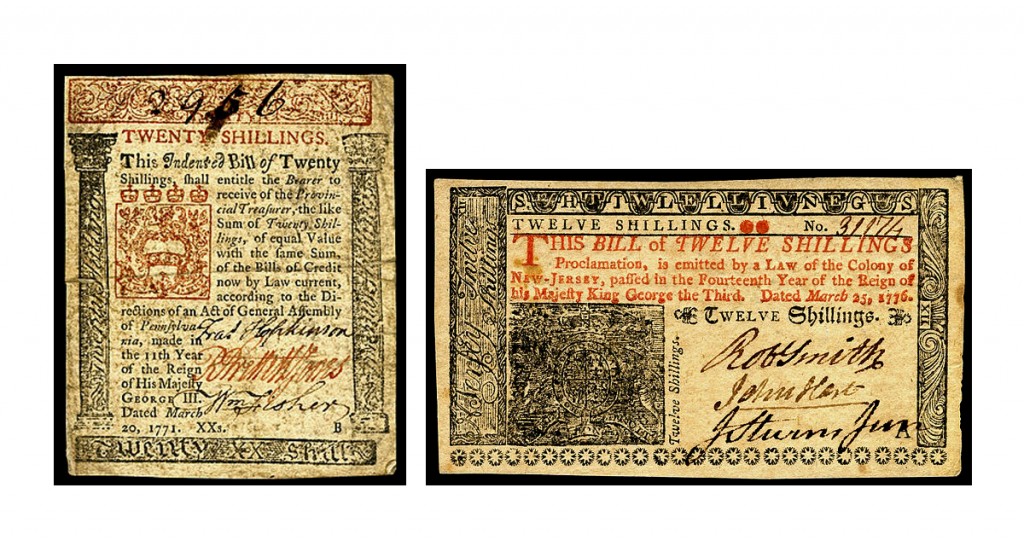

Early American paper money is separated into two categories: colonial currency, issued by the individual colonies as early as 1690 and continental currency, issued from 1775 until 1779 by the newly formed Continental Congress. The paper bills issued by the colonies were known as “bills of credit”. Figure 1 presents examples of the Pennsylvania twenty shillings bill and the twelve shillings New Jersey bill.

Figure 1. Pennsylvania and New Jersey Colonial Currency

After the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, the Continental Congress began issuing paper money known as continental currency, or Continentals. Continental currency was denominated in dollars from 1/6 of a dollar to $80, including many odd denominations in between. The bills were signed with red and brown ink and numbered in dark red ink. The obverse and reverse of the $3 currency are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Obverse and Reverse of $3 Continental Currency

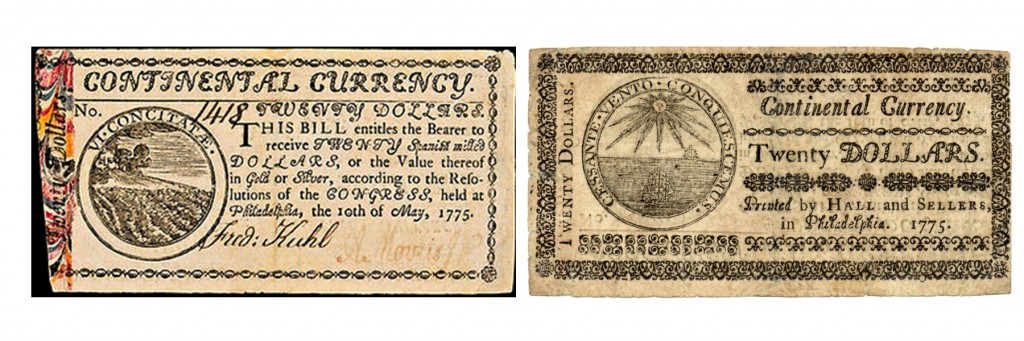

Most colonial and continental currency are not especially valuable. The exception is the unique $20 denomination from the May 10, 1775 series which was printed on paper made by Benjamin Franklin that was thin white with the left side polychromed by marbling. This bill is also a different size from the other denominations. Figure 3 shows the obverse and reverse of a $20 specimen, numbered 1418, as seen in the upper left of the bill.

Figure 3. Obverse and Reverse of $20 Continental Currency

But why were the $20 bills printed in such a unique fashion? With the issuance of continental currency in 1775, the British immediately attempted to weaken the public trust in the currency with propaganda and penalties for using the new currency. But more significantly, in an effort to devalue and destabilize the currency of the Colonies, the British also engaged in economic warfare by means of extensive counterfeiting.

Kenneth Scott’s Counterfeiting in Colonial America includes a quote from Benjamin Franklin regarding the British-sponsored counterfeits:

“Paper money was in those times our universal currency. But, it being the instrument with which we combated our enemies, they resolved to deprive us of its use by depreciating it; and the most effectual means they could contrive was to counterfeit it.

The artists they employed performed so well, that immense quantities of these counterfeits, which issued from the British government in New York, were circulated among the inhabitants of all the States before the fraud was detected.

This operated considerably in depreciating the whole mass, first, by the vast additional quantity, and next by the uncertainty in distinguishing the true from the false; and the depreciation was a loss to all and the ruin of many.”

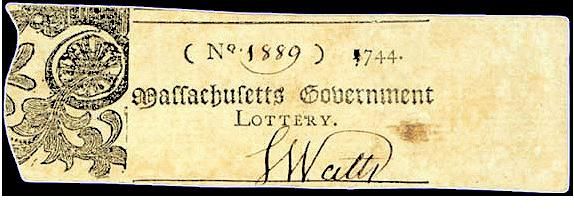

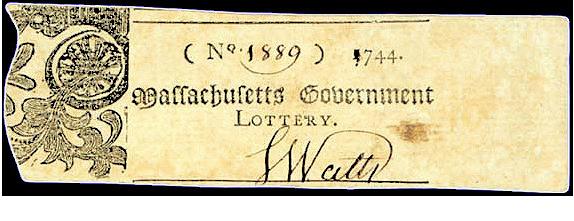

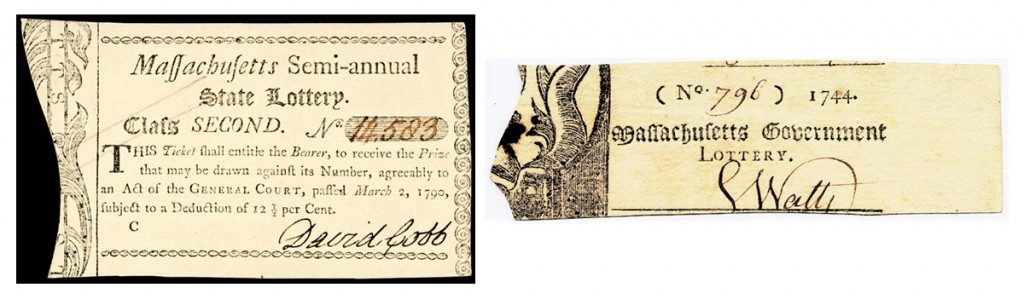

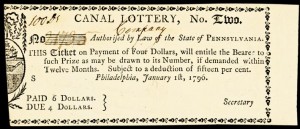

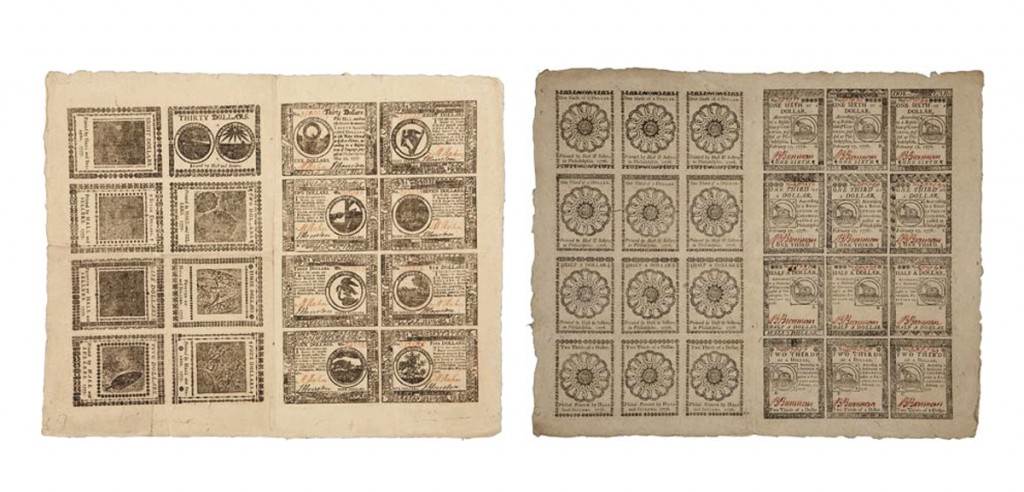

Among the solutions utilized to respond to the circulation of British counterfeits was the distribution of counterfeit detector sheets, a means by which to compare similar-looking bills in an attempt to determine the true authenticity of the continental bills. In Figure 4 are two such counterfeit detector sheets.

Figure 4. British Counterfeit Detector Sheets

However, an additional response to the British counterfeiting was needed, one that would hopefully deter counterfeiting by making the bills difficult to replicate. The adopted strategy was for the continental bills to be printed on paper containing mica flakes and blue fibers. Special type fonts, complex vignettes, elaborate border designs, and specially designed emblems were used. Also, two-color printing, as well as subtle alterations in the alignment of text, capitalization, and italicization, were used in the constant battle against counterfeiting.

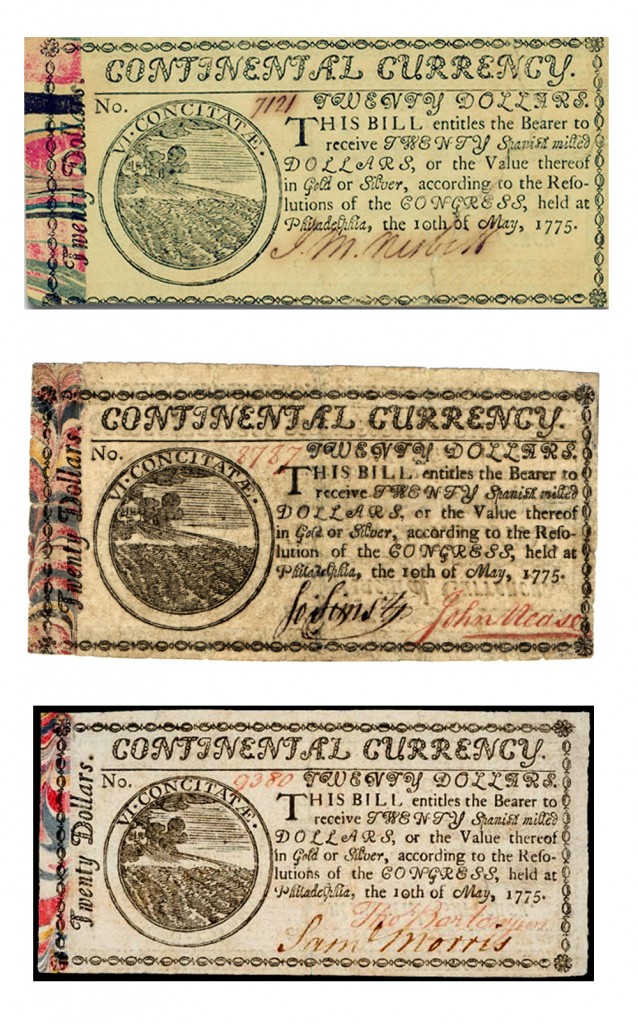

Moreover, in the single instance of the May 10, 1775, $20 bill, marbled edge paper was used as another anticipated deterrent to counterfeiting. These gems of American history have commanded prices as high as $26,000 at auctions. Granted, such prices depend on the quality of the specimen, such as all of the outer margins are fully upon the paper, both the face and back; the rich colors on the marbled portion at the far left edge are bright and fresh; the note has strong black printed text and designs and the reverse side print is as intense and vivid black. Figure 5 shows quality specimens of the marbled edge of $20 Continental.

Figure 5. The $20 Marbled Edge Currency

In the final analysis, was using marbled edge paper a deterrent to British counterfeiting? Possibly, at some level, but not completely satisfactory. But it should be noted that the lack of public confidence in the continental currency was not primarily a result of massive amounts of counterfeit bills printed by the British. The Continental Congress also printed huge quantities of the bills without any solid backing, such as gold or silver. By the end of 1778, Continentals could command only 1/5 to 1/7 of their face value. By 1780, the bills were barely worth 1/40th of their face value. Congress attempted to reform the currency by removing the old bills from circulation and issuing new ones, without success. By May 1781, Continentals had become so worthless that they ceased to circulate as money.

Endnotes

1. http://www.coinnews.net/2010/08/02/continental-currency-featured-in-heritage-boston-ana-auction/