Civil War “Dog Tags”: Sutlers Solve the ID Dilemma

During the American Civil War, soldiers were concerned that their bodies would not be identified in the aftermath of a battle because neither the Union nor Confederate government-issued identification tags, commonly called “dog tags” today. Consequently, many soldiers would write their name on a piece of paper and pin it to their clothing or scratch their name into the soft lead of their belt buckle.

On May 3, 1862, a New Yorker named John Kennedy wrote to U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton offering to manufacture and supply all Federal army soldiers a “name disc.” Kennedy’s letter and the disc design (what looks very similar to what the War Department eventually adopted forty-four years later) can be seen in the National Archives along with the Army’s reply: an abrupt rejection of the idea, no explanation. (See Journal of the American Military Institute, v. 3, 1939, pp. 61-63.)

Not long after this exchange, various manufacturers began to advertise in periodicals items called “Soldier’s Pins”. Shaped to suggest a branch of the service, these pins were engraved with the soldier’s name, unit and sometimes the battles in which the soldier had participated.

Drowne & Moore Jewelers, located in New York City, carried one of those advertisements in Harper’s Weekly: “Attention Soldiers! Every soldier should have a badge with his name marked distinctly upon it……a solid silver badge…..can be fastened to any garment.”

But soldiers in the field rarely, if ever, had possession of such periodicals and, therefore, would not be aware of the availability of these identification pins.

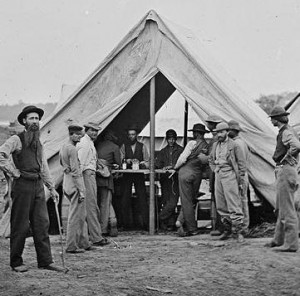

A common fixture near the Civil War battlefields were mobile tent stores operated by sutlers – itinerant, civilian merchants who followed the armies selling tobacco, coffee, sugar, and other goods directly to the soldiers. It was these sutlers who satisfied the soldiers’ desire for identification tags.

Using a small machine that would stamp designs into metal discs made of brass or lead, the sutlers created the first “dog tags” used by soldiers fighting on American soil. Very few of these identification tags for Confederate soldiers have been found. The sutlers’ primary market were Union soldiers who typically possessed the resources to purchase such ID devices.

One side of the identification tag would be stamped with a likeness of Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, an eagle, and shield or other designs. The other side of the disc was engraved with at least the soldier’s name and many times his unit and home town name. A hole would be punched into the tag allowing for a piece of string or cord to be passed through, thus finishing the piece that would be worn around the soldier’s neck.

This dog tag was inscribed for and worn by “ROBERT LUCAS / CO. K. / 1st. VET. CAV. / N.Y.S.V. / WATERLOO . N. Y.”, pictured here. “N.Y.S.V.” is an abbreviation for “New York State Volunteers.” The reverse of the tag bears the image of Union Major General GEO. B. MCCLELLAN with a notation of the “WAR OF 1861”, as opposed to the “Civil War”.

Again supporting that the majority of the dog tags were designed for Union soldiers, shown here are discs portraying a “UNION” shield and inscribed with “1861 / AGAINST REBELLION” and “The UNITED STATES / WAR OF 1861” with the likeness of an American eagle.

The similarities of the lettering and the positioning on the discs most certainly imply that these tags were made by the same sutler.

These dog tags were created for “A. Boyce, Co. E, 76th Reg. N.Y.S.V., Richford” and “Geo. Moore, Co. A, 76th Reg. N.Y.S.V., Virgil”.

Sadly, even though many Union soldiers purchased, and presumably wore, the sutler’s dog tags, of the 325,230 federal soldiers who are buried in National cemeteries, 148,883 are marked unknown. It is estimated that 5% of the combined Civil War Union and Confederate dead remain unidentified.