Mining Nuggets Buried in the Fog of Time

The cultural past as codified in history books might be likened to the bare, standing steel framework of a skyscraper: we can see the broad outline, but not yet the myriad details which make the building come alive. Many a piece of printed ephemera that has somehow survived the vicissitudes of Time reveals a nugget or two of cultural information no longer available anywhere else. Much is always lost forever in the fog of passing Time, and the more Time that passes, the more that is lost.

We ephemerists come across the things we do one by one by one . . . on eBay, in dealer stock books, at flea markets, in archives, in attics. A newly unearthed or only-now-closely-examined item of ephemera can serve a number of useful purposes; to fill a gap in an existing series of related items, to serve up information about who / why / how / when / where to correct widely accepted but erroneous conventional wisdom. Collectors often agree that their’s is a “disease”, that a collection is hard to limit because so many new “finds” suggest yet more things to pursue. Each new nugget of information reveals further questions to ask, additional related items to seek. Part of the great fun of collecting is attempting to piece together from small clues unearthed in separate places a better understanding of how things really were in days gone by. Where non-collector friends and relatives see only time and money being squandered on old pieces of paper, ephemerists feel a bit like armchair Raiders of the Lost Ark or solvers of the Da Vinci Code, following breadcrumbs of obscure clues.

All of which is by way of introduction to the random items posted below, disparate pieces of ephemera each of which could be a new trailhead.

The Parisian photographer Yvon (born Pierre Yves Petit) took exceptional photographs of Paris street scenes in the 1920s-1930s when much of the flavor of more ancient Paris was still in existence. His lush gravure postcards are hugely popular. He signed his postcards, indicating his awareness that what he produced was art.

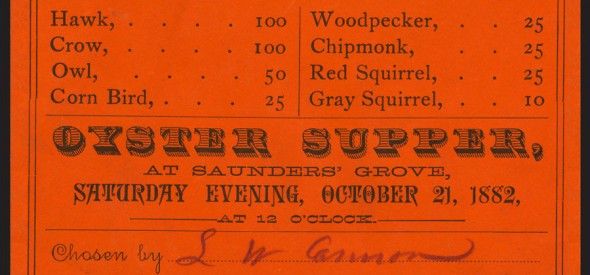

A menu for an 1882 oyster and wild game supper offers up some surprising fare . . .

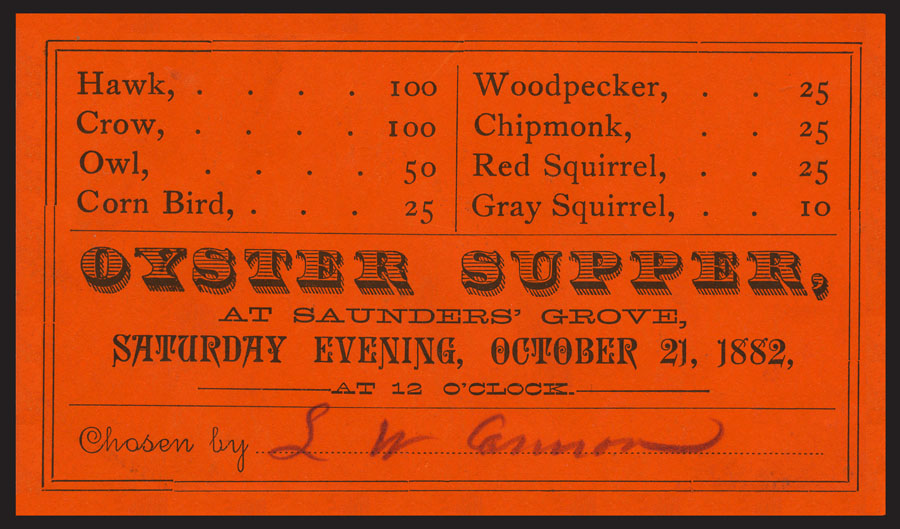

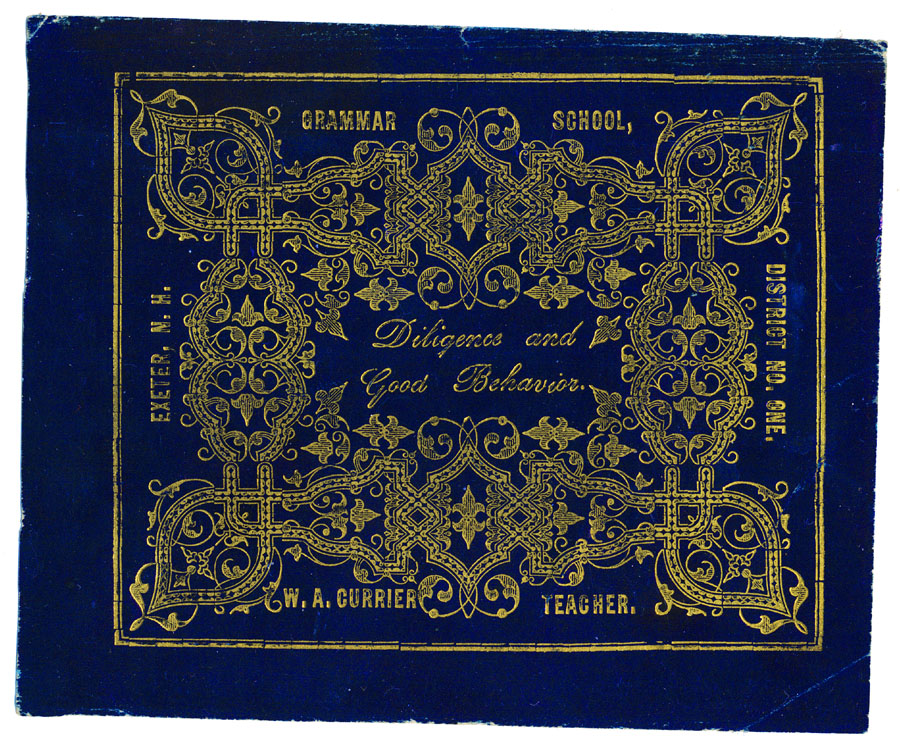

This exceptional early reward of merit is a bit puzzling, as it is printed on a thin, glazed indigo blue paper stock more commonly seen on early labels.

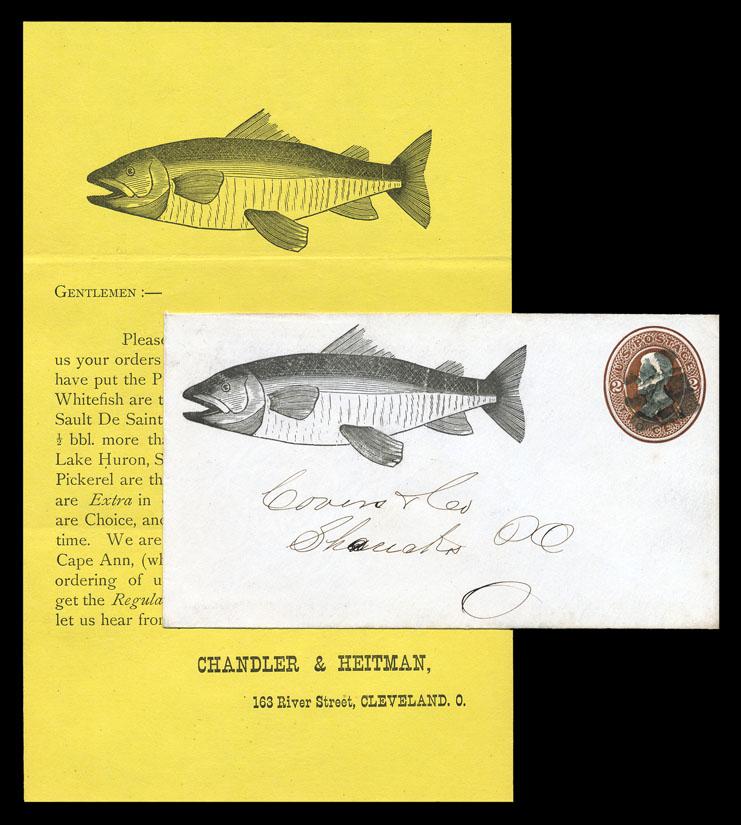

This fishmonger advertising cover and small broadside are remarkable in their clean simplicity . . . no words at all, just the fish logo. It all feels quite modern now in the 21st century. An expert on fish tells me that the one pictured here existed only in the wood engraver’s imagination, and certainly never inhabited the Great Lakes. It would appear to be a cross between a tuna, a bass, and an anchovy.

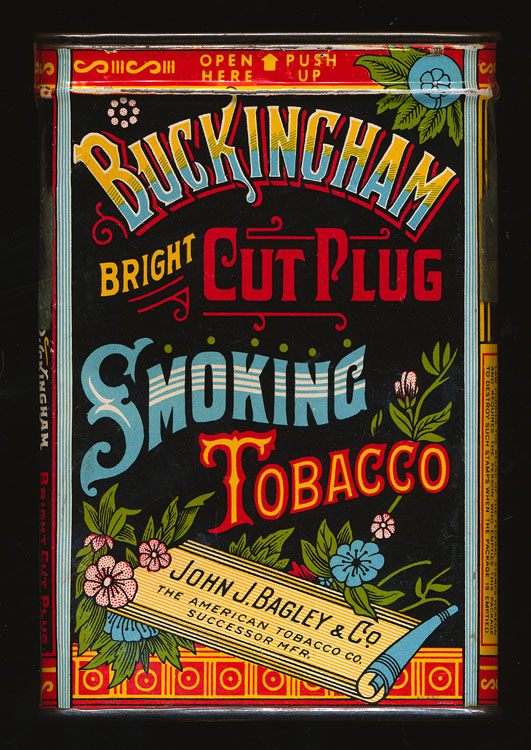

Striking, fresh looking Victorian graphics on all sides of a tobacco tin . . .

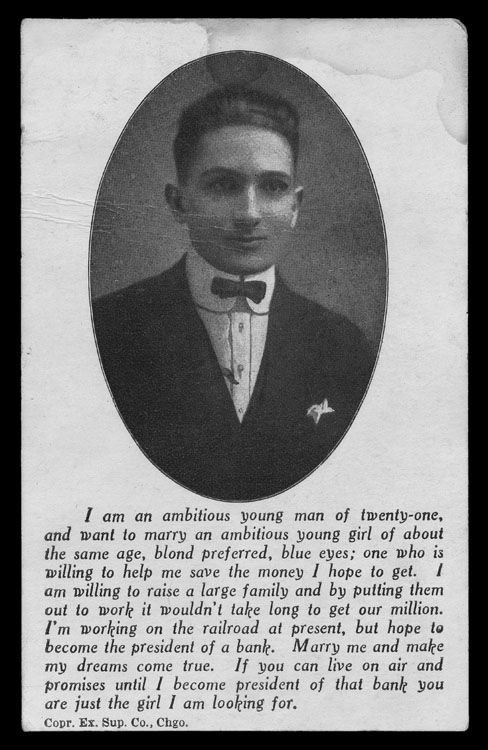

This fellow had a unique way of trying to land a wife; wonder if it worked?. Notations on the back identify him as Lloyd Buddington, August 1935, Lake Compounse (Bristol, CT)

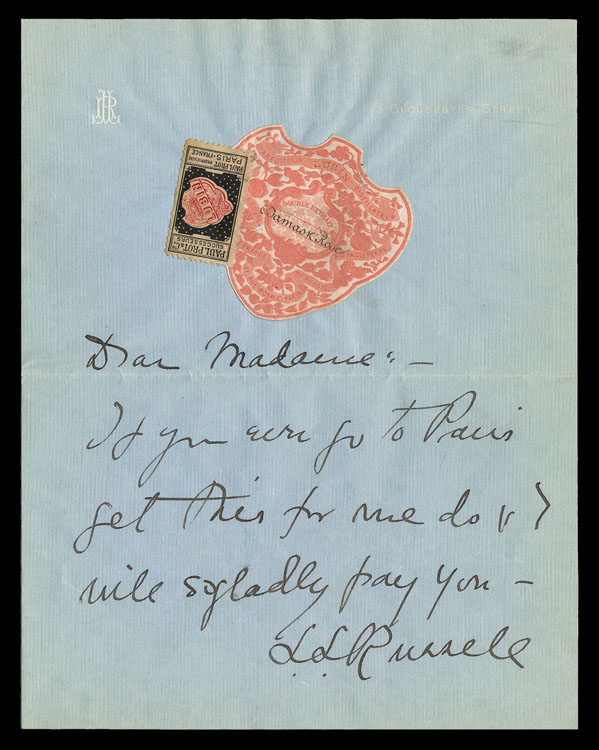

To guide an acquaintance apparently traveling to Paris, this person attached a label and stamp/seal from the Paul Prot & Co. (formerly, Lubin) brand of Damask Rose perfume requested . . .

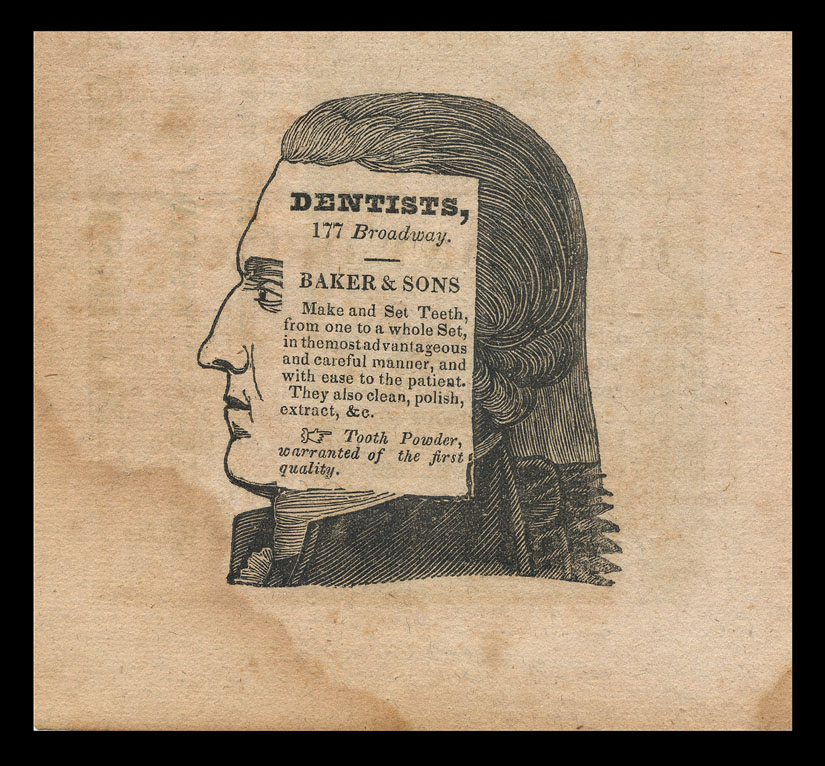

An unusual format for a dentist’s advertisement . . .

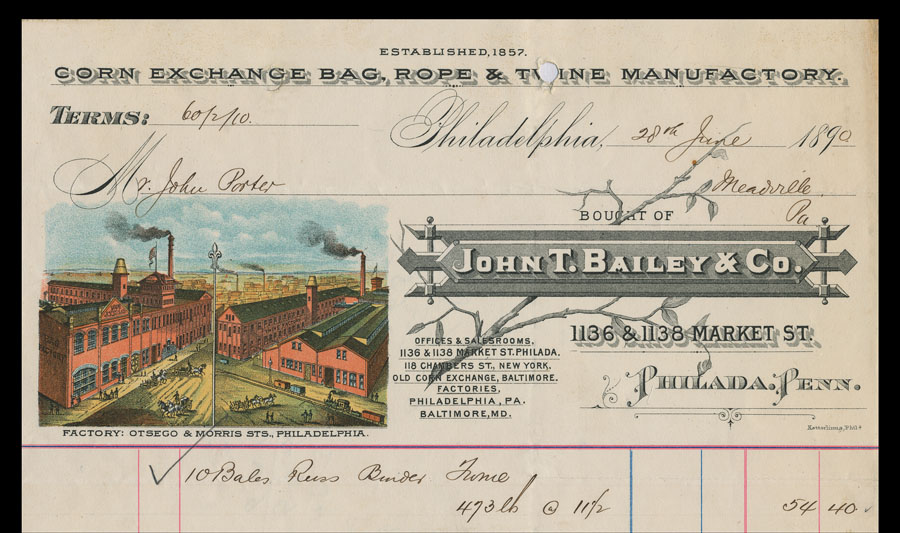

A full-color chromolithography scenic letterhead pre-1900 is not often found. The image of the two factories is unusual also because it is two different factory views sharing a common blue sky with clouds . . .

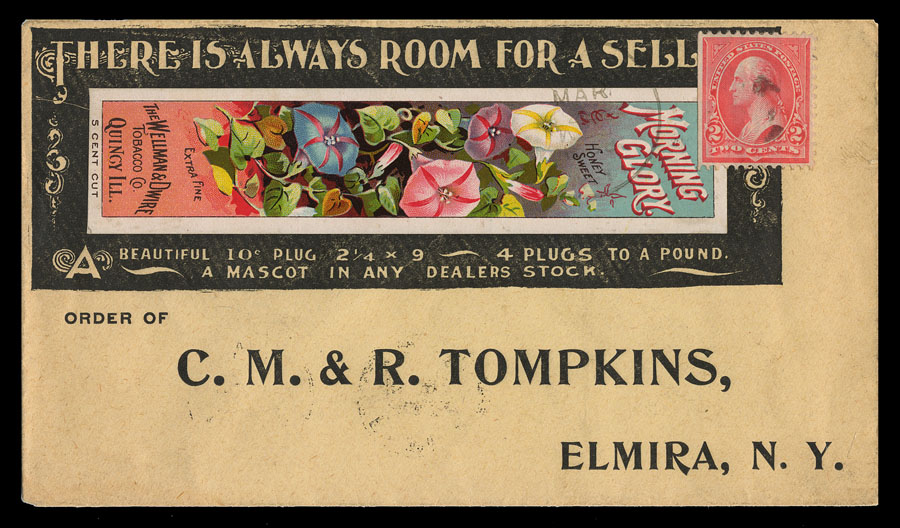

A full-color chromolithography scenic advertising cover pre-1900 is likewise not often found. The color portion of this one is actually an applied label . . .

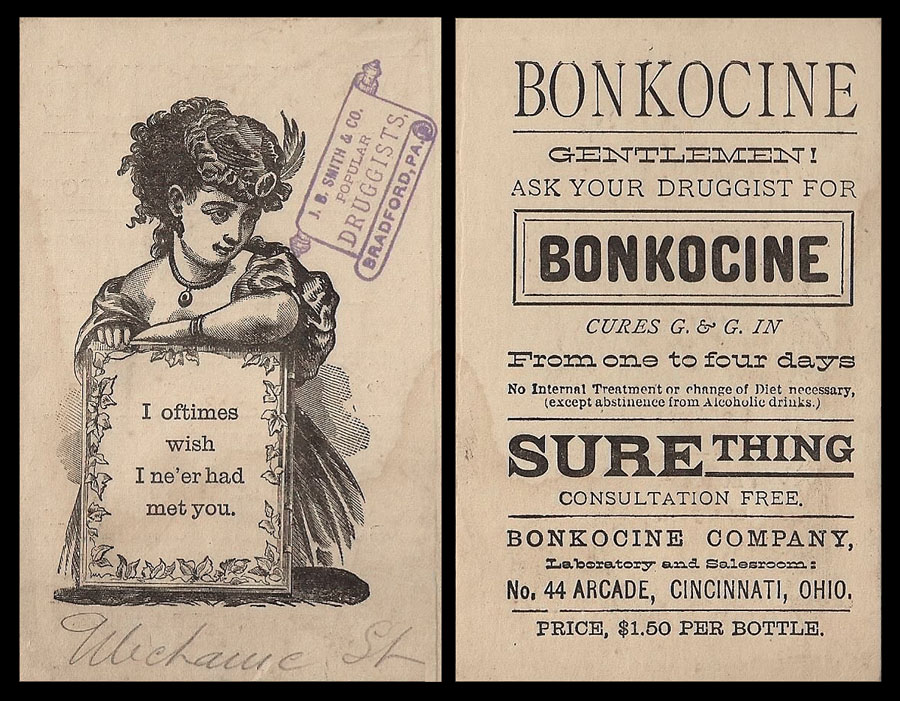

Here is something the likes of which I’d not seen before. It is a trade card featuring a stock cut of a pretty lady but clearly used to suggest that she was a prostitute some fellow wishes he had never met . . . all a promotion for a cure for venereal diseases (“Cures G & G” = gonorrhea and gleet). And then there is the matter of the name of the cure, Bonkocine. An online look tells me that the use of the verb “to bonk” likely originated in the 1970s. And yet here is this, one hundred years earlier . . .

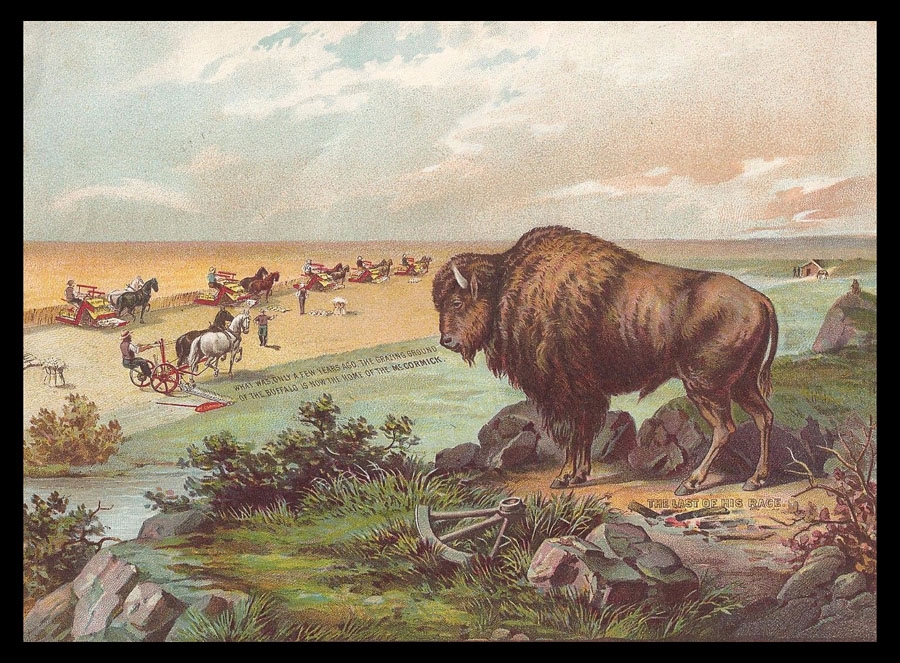

One recognized collecting area is 19th-century images of Indians looking down from some height of land at the white man’s alleged “progress” . . . cities, factories, farms. Here a bison labeled “The Last of His Breed” gazes down; “What was only a few years ago the grazing ground of the buffalo is now the home of the McCormick” (agricultural equipment).

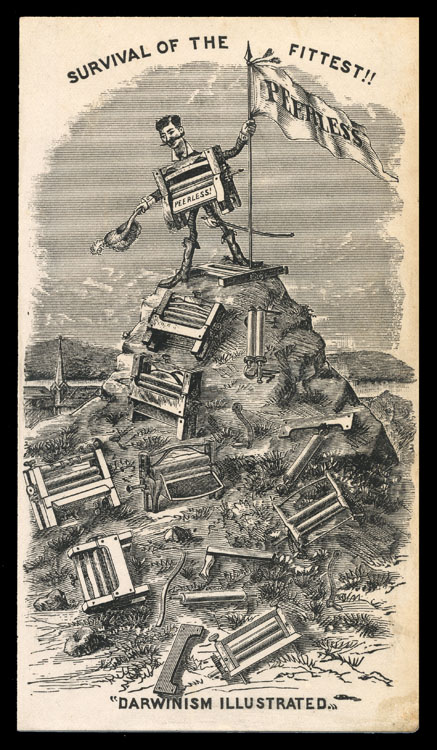

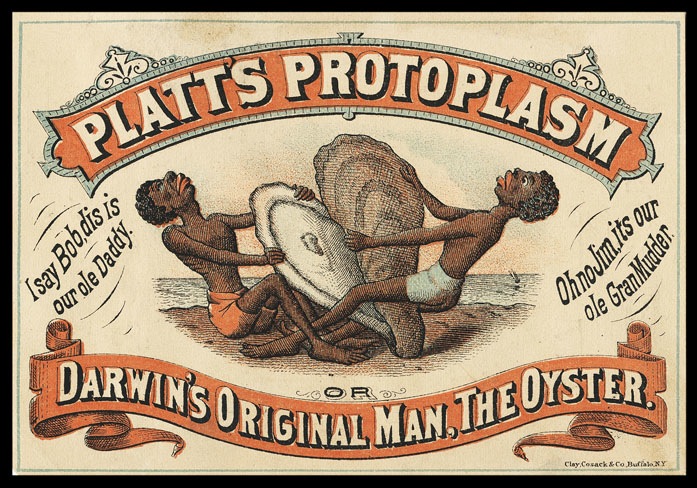

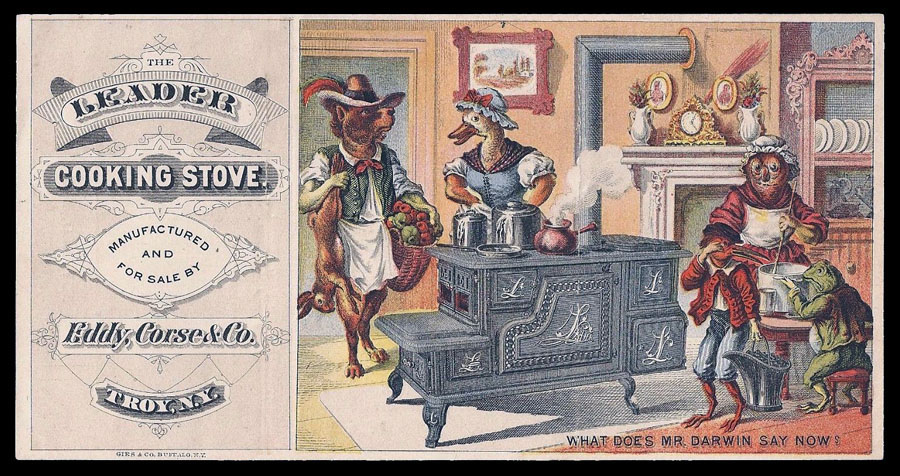

Allusions to Charles Darwin’s then-controversial 1859 book, The Origin of Species, surface in various trade cards and other ephemera, sometimes displaying the overt racism of the 19th century . . .

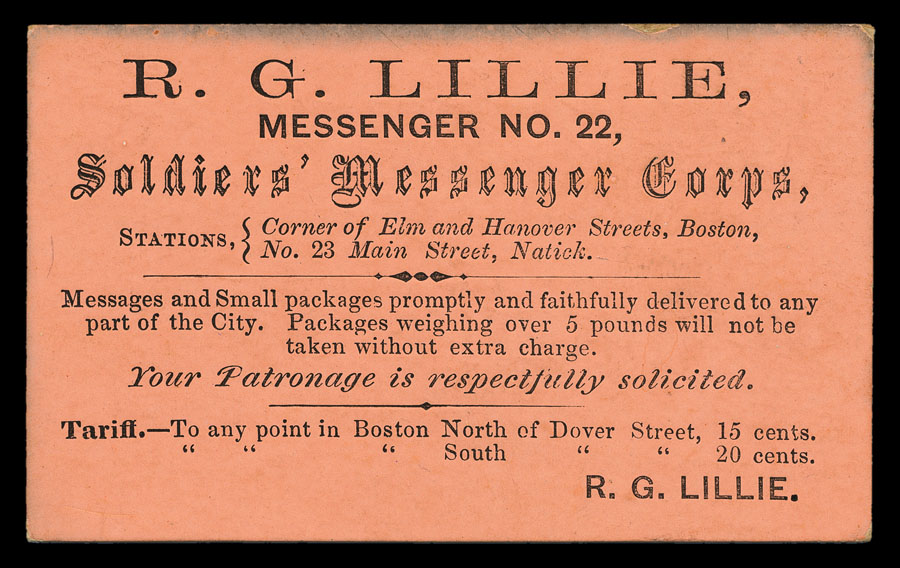

The Soldiers’ Messenger Corps was “A system of public messengers organized in this city under the auspices of the Bureau of Employment for Discharged Soldiers. The soldiers are placed at various stations where they can be called upon to convey parcels, messages, &c., to any part of the city. The first messenger, a one-armed veteran, took his station at No. 69 Wall Street yesterday. ——— The uniform of the messengers is blue, and they will wear on their caps a badge, with the letters ‘S.M.C.’ signifying Soldiers’ Messenger Corps.” (New York Times, August 19, 1865) Each received a commission and a certificate. As indicated on the salmon coated stock card below, the system was also set up in Boston. Bacon’s Dictionary of Boston, 1886, offers great detail about the various stations and routes in Boston, where the official garb was “a red fatigue cap marked “’Soldiers’ Messenger Corps”.

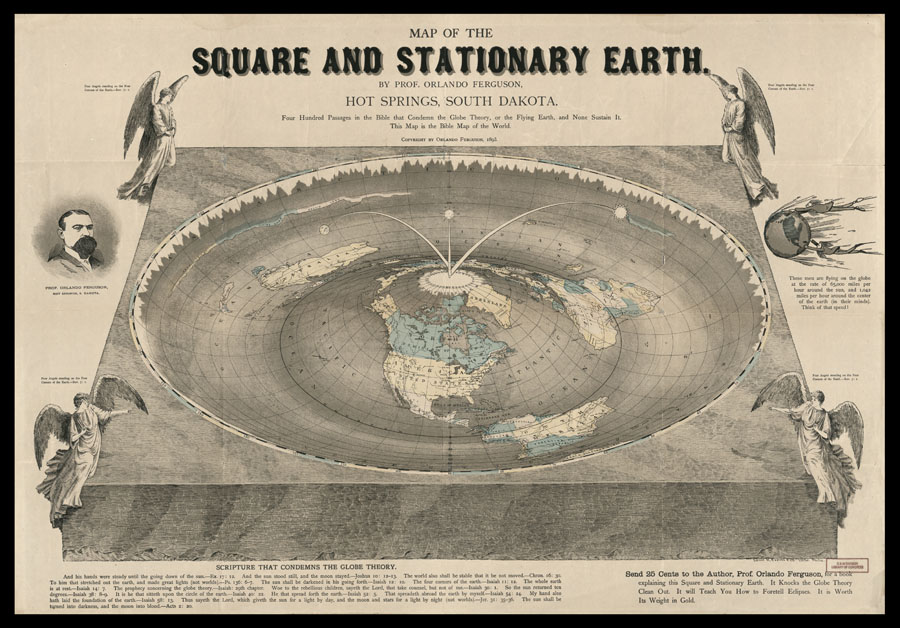

There are maps and there are maps. True believers of every stripe have long come to all sorts of strange conclusions based upon passages selectively mined from the Bible. A “Professor Orlando Ferguson” copyrighted this 1893 map “proving” that the world is flat, with an angel at each corner, and that the sun revolves around the earth. He also ridicules the idea that if the earth revolved around the sun, it would have to be moving at thousands of miles per hour (which, of course, we now know to be the case).

This unusually small (4 3/4? x “3) divided back postcard appears to show that Mr. Monsen was offered “your ad goes here” space on his company vehicle . . . and patting himself on the back for such “clever and original exploitation”.

A 1955 greeting card joking about its McCarthy era paranoia (“but don’t worry, you’re in the clear”) . . .