The Secret Life of Victorian Cards

Like other forms of mass-produced ephemera cards of all types proliferated with the new technologies of the mid-1800s, allowing for increased social interaction and the regulation of social standards that characterized the Victorian era.

As the 19th century progressed, rules of deportment became more rigid, and cards helped define the complicated new social code and express its growing sentimentality.

Like the lace flounces and beribboned furbelows of women’s dresses that concealed the stifling steel and whalebone corsets beneath, the honeycomb tissue, hearts and flowers, and elaborate typography of Victorian cards concealed an unrelenting and faintly sinister protocol. Adherence to that protocol determined membership in the burgeoning club of middle class “wannabes” whose values cards both reflected and reinforced. Cards were the ambassadors of social convention, and their subtle, covert messages were well understood by those who used them as tools in the creation of an image of respectability in an increasingly demanding and judgemental world.

Particularly noteworthy are cards of social and cultural significance such as the visiting card. In Our Deportment, published in 1890, John Young observes: “To the unrefined or under-bred, the visiting card is but a trifling and insignificant bit of social paper; but to the cultured disciple of social law, it conveys a subtle and unmistakable intelligence. Its texture, style of engraving, and even the hour of leaving it to combine to place the stranger, whose name it bears, in a pleasant or a disagreeable attitude, even before his manners, conversation and face have been able to explain his social position.”Because so much of one’s daily activities were strictly circumscribed, Victorian life was imbued with hidden meanings. There were secret languages of flowers, fans, even hair, and what more effective way to subtly or covertly communicate secret messages than in a card? If the right upper corner of the card was turned down, it signified a visit had been made; the left upper corner, felicitation; the left lower corner, condolence; the right lower corner, pour prendre congé, or farewell. Often these discreet messages were left on silver salvers, obviating the necessity of the donor and recipient actually seeing each other and engaging in meaningful conversation.

Mourning cards and cards of condolence were part of a larger convention that saw the practices and paraphernalia of mourning proliferate exponentially following the death of Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, in 1861. Certainly, black clothing and memorial jewelry fashioned from the hair of the deceased had been part of the social scene before this national catastrophe, but a show of respect rapidly turned into a full-fledged cult of mourning, much of it affecting and targeting women. It included the wearing of uncomfortable fabrics for protracted periods, black jet jewelry, and such ostentatious trappings of sorrow as coffin plates, elaborate wreaths, and black-bordered stationery. Memorial cards announced the sad event with the aid of a complete iconography of death, including urns, weeping willows, and even weepier women. John Young writes, “On the announcement of death it is correct to call in person at the door, to make inquiries and leave your card with the lower left-hand corner turned down. Cards can be sent to express sympathy, but notes of condolence are permissible only from intimate friends.”

Cards of all descriptions were part of the etiquette of the day, and the natural connection between the two was explained by Monfort B. Allen, M.D. and Amelia C. McGregor, M.D. in their 1896 instructional book, The Glory of Women or Love, Marriage and Maternity: “The word etiquette means a ticket, and the ceremonies of special occasions were formerly written on cards or tickets, furnished to each person who took part in them. Such cards are still delivered, in some places, to the mourners at funerals, and we have bills of fare at dinners, the order of dancing at balls, and programs at entertainments. So cards of invitation tell us that there is to be dancing, and cards of admission sometimes specify what dress is to be worn.”

The 19th-century card encompassed a surprisingly broad scope of printed ephemera for the purposes of conveying information relevant to a diverse range of social activities. In an age of ceremony, when even the most mundane activities were ritualized, and part of one’s success in life depended on the proper observance of the ritual itself, cards were one of the tools to achieve that success.

Perhaps nowhere was the observance of ritual more important than at the ball, soir�e or reception, which were minefields of social warfare. One false step (either literal or figurative) � a slight oversight in one’s apparel, ignorance of which fork to use at dinner, or an inappropriate introduction � and the consequences could be dire indeed. Within the exacting cabal of “polite society,” one might be relegated to a social no-man’s-land for the smallest infraction of the rules, where redemption would be next to impossible. Social intercourse was serious business, and leisure and cultural pastimes, which should have served as a reprieve from the demanding world of business and homemaking, were often no more than a pretence, a thin veneer concealing the public gauntlet contestants in this parlor game called “How To Be a Proper Victorian” were forced to run. Like most forms of social intercourse, the protocol of the dance floor was strictly regulated. It was the runway upon which a young lady’s or gentleman’s attributes were paraded to their best advantage (or detriment), and prospective spouses and their parents could size up the candidates and the competition.

Into this war zone enters the dance card. Essentially a program with the order of the dances and blanks for recording engagements for each, they were distributed to the guests�both male and female�as they entered the ballroom. Each card would be attached to a small pencil. “My dance card is full” was a situation in which most young ladies hoped to find themselves. Dangling delectably from dainty wrists or waistbands throughout the evening, or tucked into beaded reticules, dance cards could be elaborate in the extreme, featuring colored scraps, ribbons, netting and even the occasional stuffed bird.

For a society that took itself so seriously, whose rules and code of ethics were both immutable and sacrosanct, the chromo- lithographed greeting cards which proliferated during the 19thcentury reflected a tendency toward sentimentality that was becoming a hallmark of Victorian popular culture, providing evidence that the Victorians were not all as stuffed as their shirts or as starched as their collars. They did have a romantic, whimsical, fun-loving side.

Long before the first Christmas card was printed in 1843, Queen Victoria’s mother, the Duchess of Kent, distributed beautifully crafted German cards, including Biedermeiers, to the members of the household at New Year’s, created by such renowned designers as H.F. Muller and Joseph Entletzberger, both of Vienna. An illustration of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their children around a table-top tree laden with gifts and candles appeared in the Illustrated London News in 1848, and thus began the celebration of the Victorian Christmas. Queen Victoria herself did much to ensure the commercial success of this new medium, and for a time she practically sustained the entire Christmas card industry single-handedly, granting Raphael Tuck a Royal Warrant in 1893 to produce thousands of cards to be sent to friends, family, and neighbors at Windsor and Osborne.

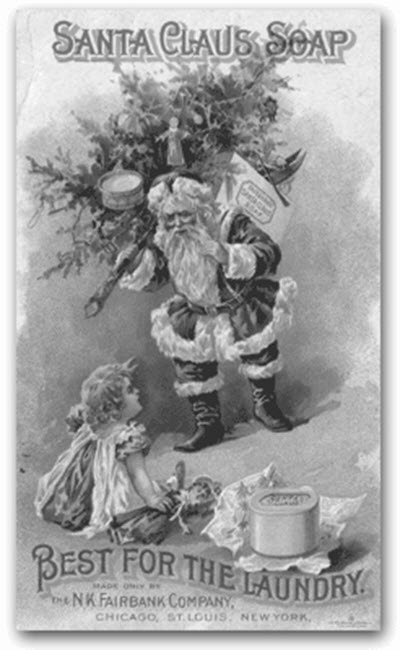

By the 1890s Christmas cards were being exchanged in the hundreds of thousands. Though there were some elaborate cr�che scenes, Christmas cards, both English and American, tended to reflect the preoccupations of the society that produced them rather than the religious festival they were intended to commemorate. Santa Claus and Father Christmas, gadgets and gizmos, and modes of transportation were all extremely popular.

Following Christmas was Valentine’s Day. The tradition of composing rhyming love letters on Valentine’s Day was established by the 15th century and had evolved by the 17thto amorous addresses or verses. Hand-drawn valentines and love notes were popular throughout the 19th century. Commercial valentines were available in England by the early 1800s, and in America shortly thereafter. By mid-century, valentine makers such as Joseph Mansell in England and Esther Howland, who in 1848 set up a production line in her home in Worcester, Mass., were assembling gorgeous confections composed of layers of embossed and lace paper decorated with cupids, hearts, and other traditional symbols of Valentine’s Day. By the 1880s, mass color printing had added a new dimension to the valentine in the form of German-made pop-up chromolithographs. Die-cut and embossed on heavy cardboard stock, these elaborate confections featured scraps of cherubs, flowers, elegant women, and rosy-cheeked children set against gilt and floral backdrops. Red or pink tissue paper in honeycomb shapes added drama when the cards were opened. As with the Christmas cards, around the turn of the century motor cars, steamships, and trains became focal points.

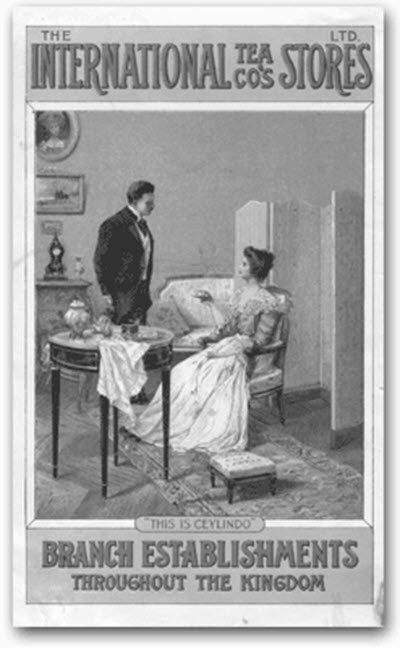

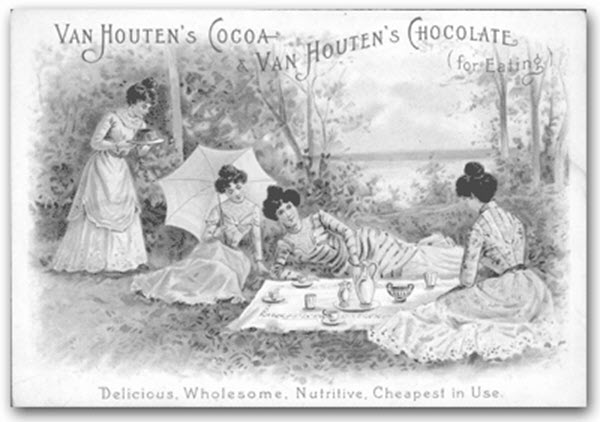

Not unexpectedly, the technology used to exchange greetings was also employed in the advancement of the new culture of commerce. With their covert messages and vivid images, trade cards promoted not only the new packaged products but the new social order. Individually, each of these little artifacts has a story to tell. Taken together, they weave a narrative of daily life in the 19th century.

Trade cards were more than pretty pictures to those who pasted them into albums and tucked them into shoeboxes for another generation to discover. More than anything else they represented miniature replicas of the Victorians as they saw themselves � or wished to � mothers, fathers, children, successful members of the community and those who couldn’t make the grade. The icons were instantly recognizable, tiny mirror images reflecting an individual, a community or a nation, and just as 100 years later we seek to identify with those whom society has deemed the best and the most beautiful, so the Victorians sought to align themselves with the powerful messages that defined social convention.

This was all the more important in an age that stressed conformity and status, and collecting these colorful images was more than just a hobby � it was a kind of navel-gazing, a congratulatory act of self-indulgence and a tribute to their ingenuity. The Victorians were desperate to define themselves in terms of the level of industrial progress and material success they had achieved, and trade cards were a double bonus: not only did they represent flattering images of middle class America artistically rendered, but they served as rewards of merit, offered free of charge as a prize simply for being conscientious consumers.

As a profusion of printed words and images entered into the experience of ordinary people, trade cards became an important means by which rules and standards were defined and disseminated, much as television affected our lives in the last half of the 20thcentury. By the end of the gilded age, these visual bulletins served much the same purpose as parents and teachers, bombarding young children with models of acceptable behavior and with social and cultural values. This popular imagery functioned in complex ways. It reflected contemporary opinions since it aimed to please and persuade the viewer, but it also influenced social attitudes, since the repeated messages formed and reinforced contemporary standards and evolving values. Trade cards acted as a camera lens, not simply recording social convention, but helping define and create it. Images on trade cards portrayed a sanitized version of 19th-century life, complete with blissfully happy families, beautifully coiffed women, healthy, well-behaved children, and products that promised solutions to all of life’s problems. The Victorian age ushered in dramatic economic and social changes, and trade cards traced the journey from once predominantly agrarian American to the new urban realities.

The use of cards in 19th-century daily life represented and helped define class, breeding, and status. They were a form of social contract, a common language, and ideology through which the Victorians communicated with one another, maintained moral standards and disseminated popular culture. With their vivid images of upwardly mobile over-achievers and messages of love, condolence, and purchasing power, cards identified individuals as belonging to the consumer culture, having the time to enjoy leisure hours, the means to purchase goods, the predisposition to celebrate intimate occasions with loved ones, and to pay proper homage to them when they departed this world.

They are evidence of the formal ritualization of daily life, an admission ticket to an elite and prestigious club that represented the new social order. One contemporary commentator of the Victorian social scene observed that “the higher the civilization of a community, the more careful it is to preserve the elegance of its social forms.”If so, Victorian cards represent one of the highest forms of expression of that age of ceremony and ritual.