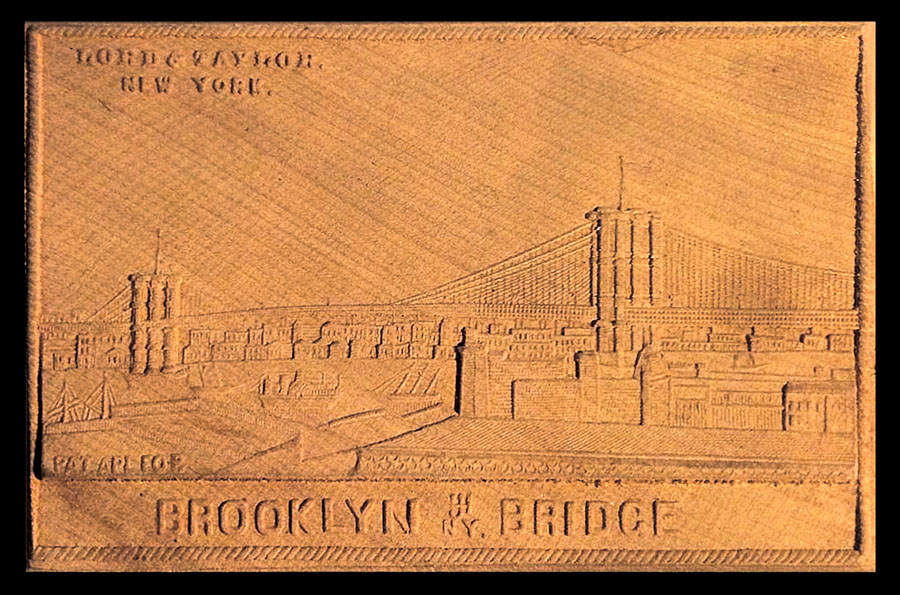

Die-Stamped Wooden Trade Card

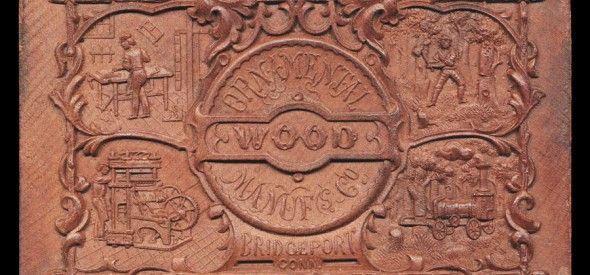

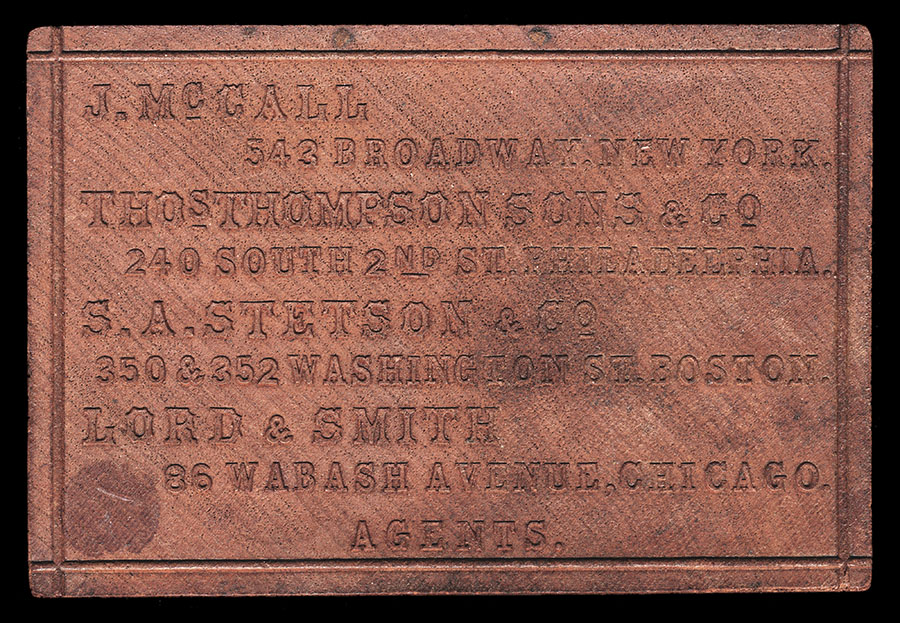

One prized acquisition at the recent Ephemera Society conference and fair in Greenwich was a trade card, apparently, made of wood! Produced by the Ornamental Wood Manufacturing Company of Bridgeport, CT, bearing a patent date of October 18, 1865, it measures @4 1/4” x 2 3/4”, and is @ 1/4“ thick.

My first question about this quite unusual 1860s “trade card” was whether it is, in fact, made of wood; and if so, whether it is completely wooden. Or might it instead be some composite such as gutta percha? Or wood with applied composite for the details? Preliminary research has turned up quite a bit of information. It is 100% wood, likely black walnut. No doubt is was meant to do double duty as a trade card (with a list of agents in several cities on the reverse), and a salesman’s sample of the quality of embossing which could be done by the firm.

The Ornamental Wood Manufacturing Company of Bridgeport was founded in 1867 by Henry (William H.) May and Clapp Spooner, and remained in business until 1889. May was the holder of 1865 patent No. 50,608 (plus several later patents), which read in part that his process was a “new and useful Improvement in Stamping or Molding of Wood” . . . “The pieces of wood to be pressed or molded are cut from the end of the log or timber in sheets or cross-sections, having the face or faces upon which the impression is to be made transverse to the grain. The pieces of wood, having been thoroughly seasoned or otherwise freed from moisture of water or sap, are placed under, between, or within dies or molds of any desirable form, in such a manner that a heavy pressure may be made upon the end of the grain of the wood, and the pieces of wood, when thus placed, are subjected to a single and short pressure by such dies or molds, the pressure being applied against the end of the grain and in a direction as nearly as possible paralleled with the grain. Such pressure, having been applied is then removed and the wood released from such dies or molds without unnecessary delay.”

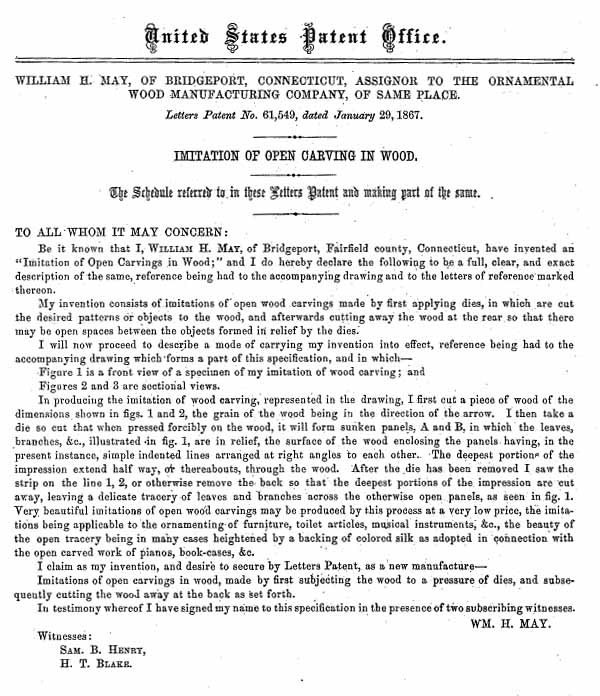

An 1867 patent of May’s, taking the process a bit further by cutting through from the back, resulting in open fretwork in places.

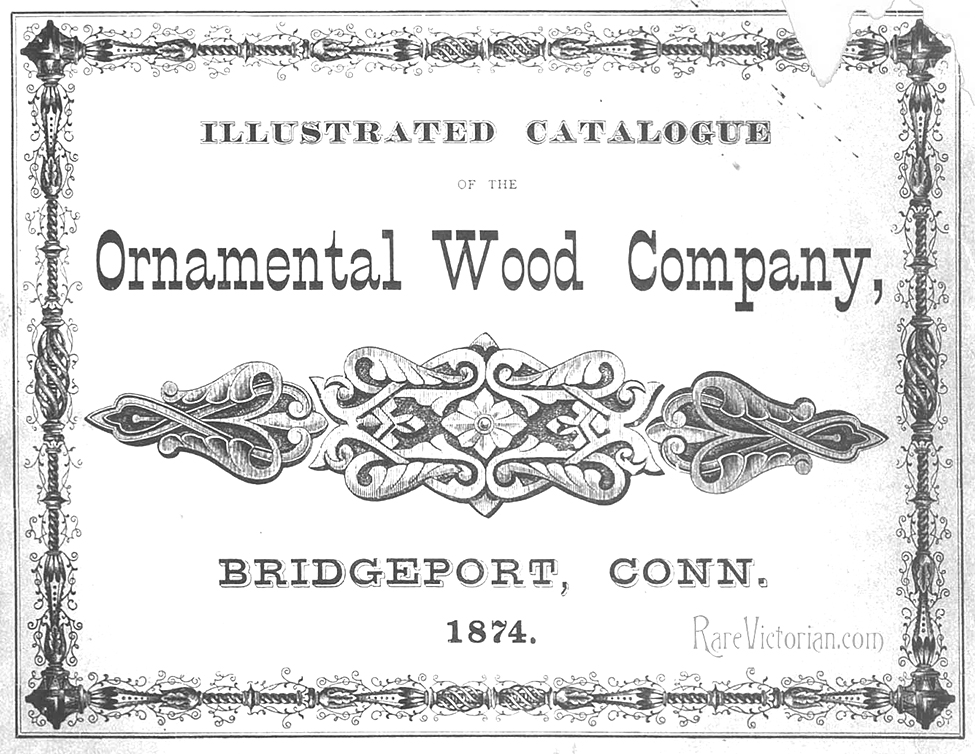

May’s Ornamental Wood Manufacturing Company (OWMCo) advertised in 1869 a variety of pressed wood products: “Medallions, Curtain Pins, Rosettes, Monograms, etc.” An OWMCo 1874 catalog (copies at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and at RareVictorian.com) also offered doorknobs, brackets, sleeve buttons, shutter knobs, panel ornaments, jewel boxes, buttons, and escutcheons. May’s commemorative medallions in several varieties were offered for sale at the 1869 National Peace Jubilee in Boston.

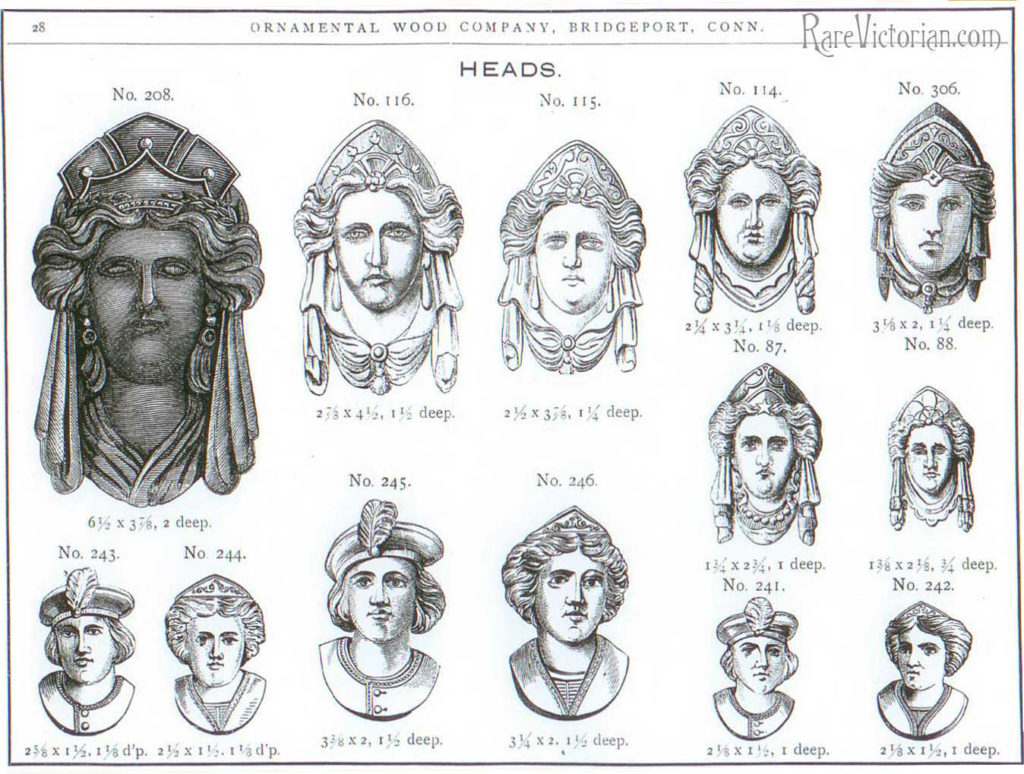

These are the sort of pressed wood decorative furniture embellishments produced by William H. May’s Ornamental Wood Manufacturing Company in Bridgeport and other makers.

An interior doorknob (Sheaff collection) made by the Ornamental Wood Manufacturing Company and a group of their matching drawer pulls.

The cover and one page from the OWMCo 1874 trade catalog (courtesy RareVictorian.com)

There are two excellent, definitive reference articles on this subject by Donald G. Tritt. One appeared in the February 2012 issue of The Numismatist magazine, titled “Die-Pressed Wooden Exonumia”; the other in the July 2014 issue of The Numismatist, titled “Die-Pressed Wooden Medals & Plaques of the 1876 Centennial Exposition”, a history and catalog of the many 1876 Centennial pressed wood commemorative medallions and plaques. The 2014 article is available online at https://www.money.org/uploads/pdfs/DiePressedWoodenMedals8.26.pdf

Tritt reports that credit in America for originating the process of die-pressed wood should go to one Philander Shaw of Boston, holder of 1860 patent No.28,309; and Tritt quotes details of Shaw’s patent description. However, he also chronicles much earlier production of wooden planchet “medals” in 17th century Germany. The 2012 article also describes additional 19th-century American makers.

Though the production details of the Shaw process, the May process and the process of the Philadelphia Ornamental Wood Company (incorporated on April 29, 1876 by John H. Schreiner, Frederick C. Viney and others four days after winning a lawsuit brought by the U. S. Mint, maker of the “official” coins and medallions for the show) vary a bit, each of them used softened slabs of end-grain wood embossed with metal dies using heat and pressure. The process is directly analogous to cameo printing, and the striking of coinage, medals, and medallions in metal. Wood is, of course, softer than metal, so the idea was logical. As black walnut wood (Juglans Nigra) was in widespread favor for furniture during the Victorian era, it was usually used for these wood pressed items, especially when creating decorations to be applied to furniture. The “only wood appropriate for middle-class gentility”, opined Francis Lichten in 1950 (Decorative Art of Victoria’s Era, New York, Scribner’s, p.93; quoted it Tritt).

Tritt quotes one provider of wooden medallions for the 1876 Exposition, John Haseltine of Philadelphia, saying, “The ‘black walnut medals’, so-called are, it is said, made from woodcut with the grain, steamed until it assumes a semi-pulpy condition, then coated with shell-ac (sic), and the impression made by a squeeze and not a blow.”

Another wooden trade card, for the Philadelphia firm William A. Drown & Company, a maker of umbrellas and parasols. Likely a product of the Philadelphia Ornamental Wood Manufacturing Company. 2 3/4? x 3 5/8? (collection of George Fox; I know of one other)

This 1876 Centennial Exposition George Washington head medallion (large head version) (Yale Museum of Art)

This 1876 Centennial medallion of General Joseph Roswell Hawley was made by the Philadelphia Ornamental Wood Company. Hawley was a Civil War general, the Governor of Connecticut, a U.S. Representative and a U.S. Senator. Tritt gives information on the likely maker of the die.

(Sheaff collection)

The 1876 Centennial medallion of Independence Hall, produced on the floor of the show by the Philadelphia Ornamental Wood Manufacturing Company.

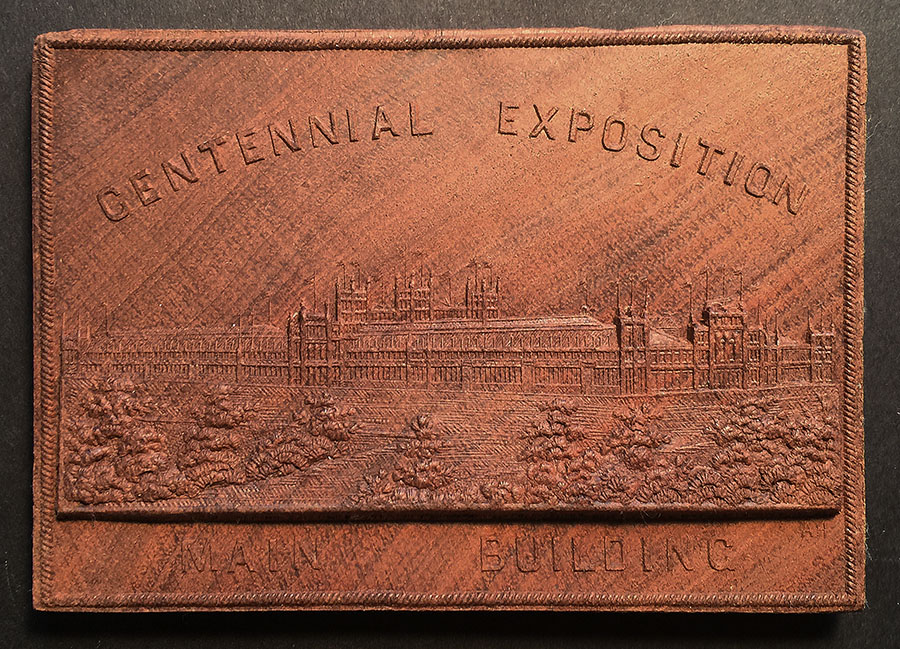

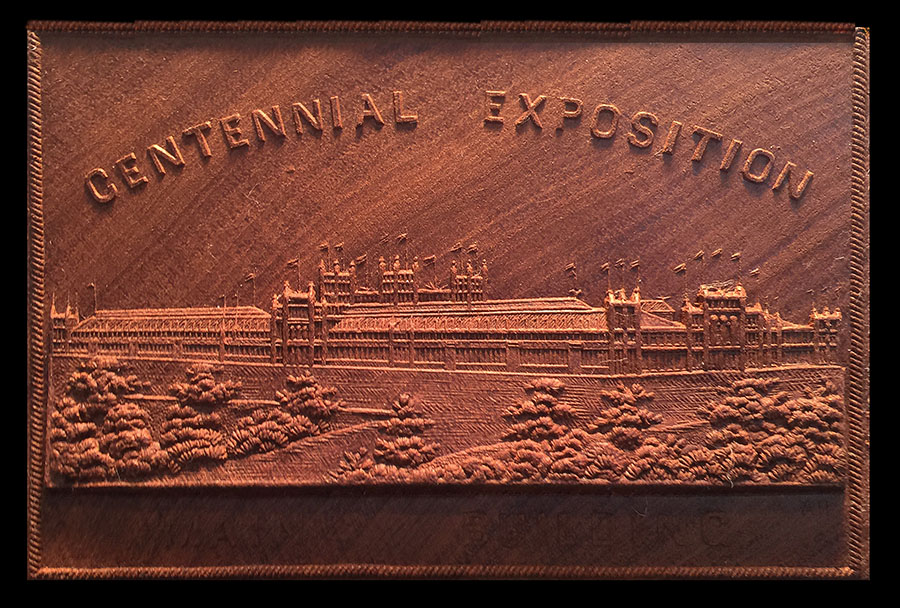

The Main Building, one of a set of four 1876 Centennial Exposition rectangular plaques. (Sheaff collection)

Agricultural Hall, one of a set of four 1876 Centennial Exposition rectangular plaques. (Sheaff collection)

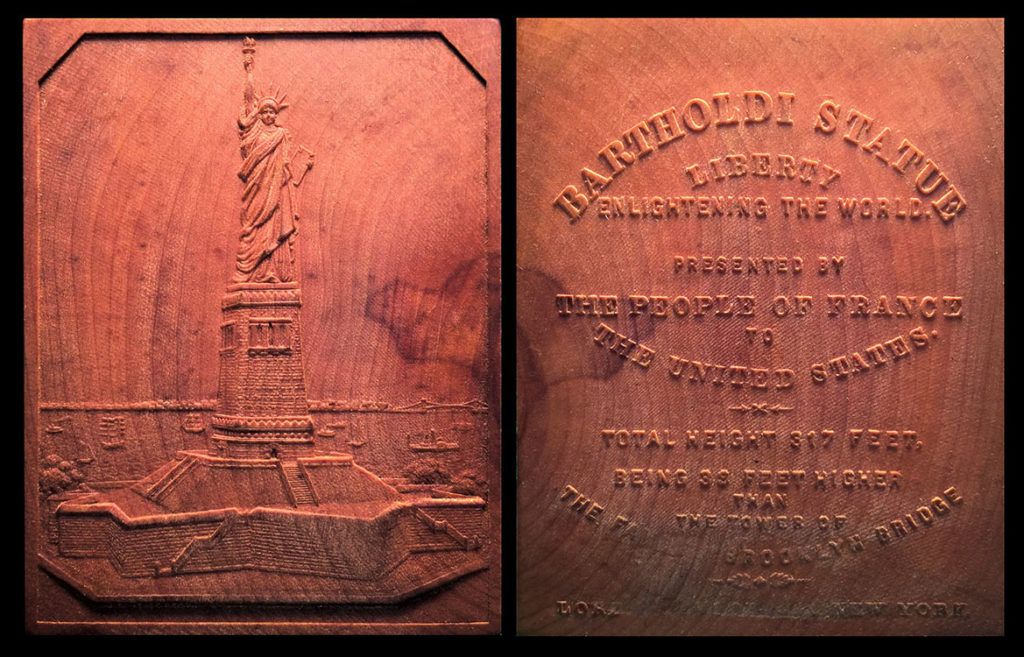

Statue of Liberty commemorative rectangular plaque put out by Lord & Taylor (last line of time on the reverse, in shadow in this image). (Sheaff collection) Lord & Taylor sponsored a similar plaque for the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge (below).

I have located three additional, different wooden trade cards in private collections. The hunt continues . . . anybody out there have a different wooden 19th-century trade card to report?