Engraved Social Stationery

The engraving of social stationery has long been a small but vital industry originating in Western Europe and subsequently practiced in the Americas and in the more affluent countries of the far East. Social stationery played a symbolic role in the literature of socially conscious writers such as Arthur Schnitzler, Henry James, Edith Wharton, and Bret Easton Ellis. Even Jack London sweated over the correct use of calling cards while courting a young lady.

Each year fewer and fewer social stationers survive. The process for making commercial engraving dies and plates is arcane; craftsmen are few, rarely appreciated and commonly underpaid. Forty years ago there were nearly a thousand commercial engravers in this country, today perhaps only a hundred. As more and more of these companies cease to hand-engrave, their presses, engraving machines and thousands of gorgeous dies go to the junkyard for scrap.

Traditionally, the finest stationery has been engraved. Commencing with the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the middle class, customized personal stationery was widely sought by individuals and businesses seeking entrance to successively loftier social circles. One of the essential tools of the upwardly mobile was engraved social stationery.

Until recently most towns in America (and Western Europe) had a stationer. Those who remain continue to serve as the keepers of local mores and accepted social, creating announcements for all phases of community life . . . births, deaths, marriages, business openings and closings, graduations and formal acknowledgments of all sorts. Until the advent of desktop master plates publishing, tweeting, text messaging and the worldwide web, the papers of everyday life were the bones of our social existence. Calling cards, business cards, and stationery items have become the artifacts of localized social tradition.

The lettering styles used in modern social stationery are predictable: London Script and Block Gothic are chosen much of the time. They have been converted to digital fonts. Yet there are over three hundred other typefaces – ranging in time of creation from the Edwardian era to the 1970s – which are proprietary to the commercial engraving industry and have never been digitized. They remain in the unique Masterplate Styles system.

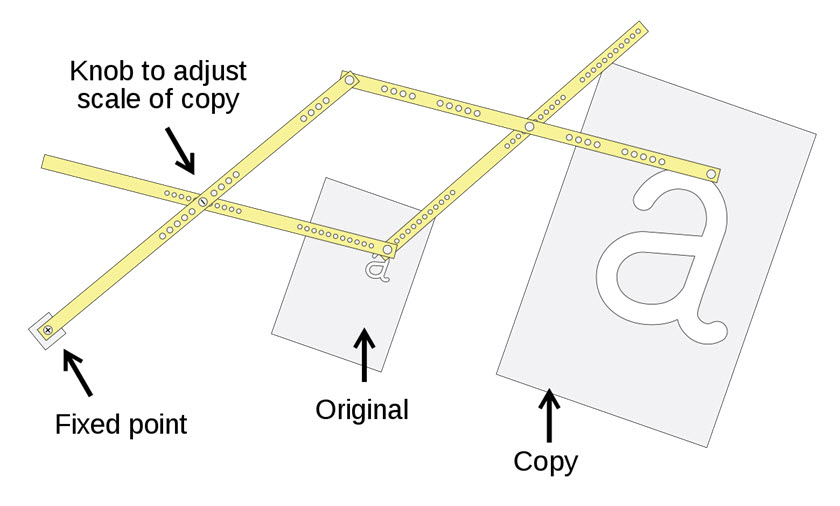

A Masterplate is a large metal template, similar to the plastic templates formerly used for architectural lettering. The characters are an inch or two high, and a pantograph is used to trace each letter into a thin piece of copper or steel (called a plate) or a thick piece of steel (called a die). As attention to detail is important and the system is capable of reducing letters to the point that a magnifying glass is required to read them, engravers typically work with a 10X loupe in one eye.

The metal will have been prepared with an acid-resistant “ground” or coating similar to that used in fine art etching. A sharp, hard needle in the pantograph machine traces the letter onto the die, scratching through the surface of the ground. Once all of the letters have been traced, the engraver applies acid with an eye-dropper onto the surface. The acid eats into the metal where exposed by the tracings of the pantograph needle. The engraver, loop in eye and face close to die, controls the process.

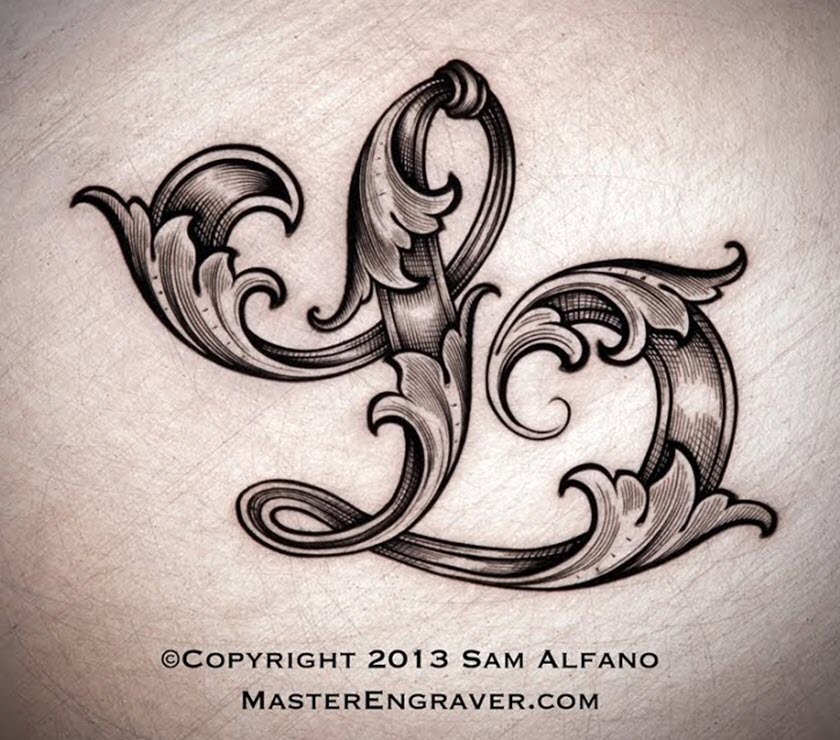

Ambient temperature, humidity, variance in quality of steel and the craftsman’s skill all factor into the success of this process. Sometimes the acid removes metal to the full required depth in sufficient detail, sometimes the engraver must finish the job by hand using a graver/burin and other traditional tools.

In addition to hundreds of sets of upper and lower case alphabets with their corresponding numerals, punctuation, and characters, Lehman Masterplate Styles also include an ingenious compositional system for engraving custom monograms and ciphers. These gothic and Victorian forms are transferred to the die in the same manner as ordinary letters but are arranged on a grid which allows the craftsperson some freedom and flexibility. Given sufficient imagination and ingenuity, a person using the Masterplate system can create quite intricate two- and three- color designs, connecting and interweaving letterforms to create the monogram.

Originally, such engraving was accomplished entirely by hand, with each line, dot and elegant curve cut with the graver/burin. In recent years it has become customary simply to acid-etch the designs and lettering, as fewer and fewer traditional engravers continue to work in the field and as costs have escalated. The term commercial engraving has become a something of a misnomer because today almost all such “engraving” is actually acid-etching, often following computer-generated patterns.

When the Cronite Company acquired The Library of Engravers Styles by Eatonin the early 70s, they came to control the largest collection of pantograph lettering templates in America. Cronite continues to manufacture, sell and service machines, materials, tools and ink for the graphic arts industry, and to manufacture pantograph machines for commercial engraving. Alas, there are but a handful of engravers left in this country who use them.

www.nancysharoncollinsstationer.com