Ephemera Collecting – A Growing Field, Hard to Define

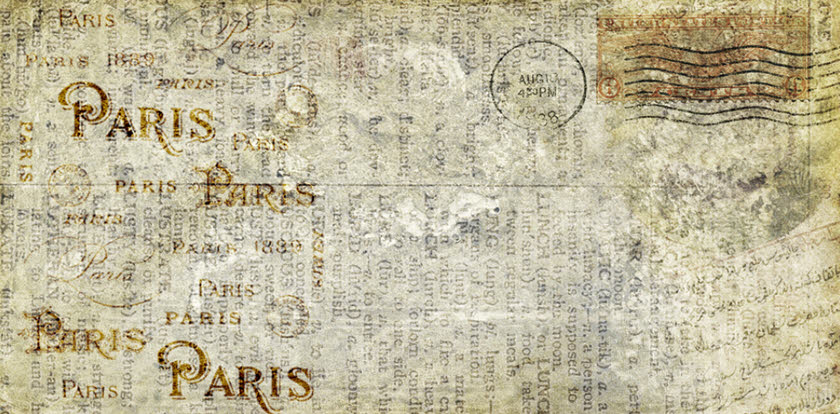

In 1980, the Ephemera Society of America came into existence and the first Ephemera Show was held. The organization has prospered and the show has become a widely anticipated fixture of the collecting world. Even the phrase “ephemera,” a somewhat equivocal term used to describe “a thing” essentially indescribable with a single word, has come to be widely understood and accepted by collectors, dealers, and librarians.

The Ephemera Society of America borrowed the term from the British Ephemera Society, which was formed in 1975. As understood by enthusiasts, the essential elements of ephemera seem to be:

- “the stuff” of which the field is made was originally produced for some immediate, practical purpose, with no thought that it would be saved or preserved (having an ephemeral existence);

- it tends to fall between the cracks of traditional collecting fields and librarianship (not books, not “art” in the formal sense, not manuscripts, not antiques);

- in its vast and fascinating diversity, it documents everyday life, particularly that of average men and women in the past, perhaps more effectively than traditional collectibles.

There is no exact catalog of ephemera’s subject matter but included under the broad umbrella are trade cards, letterheads, die cuts, postcards, broadsides, tickets, menus, timetables, posters, advertising materials of all sorts, rewards of merit, labels, political buttons, and programs.

Much of “ephemera” was originally a by-product of exuberant capitalism-largely advertising material made possible by advances in printing technology.

Prints, paintings, photographs, manuscripts, stamps, coins and currency, obscurely printed books and pamphlets, children’s books or cookbooks, objects as diverse as license plates, toys or curios are all similar enough in many respects to gain admittance to ephemera shows, but they are a bit on the periphery. The British tend to emphasize printed textual material as the only “pure” ephemera, while American collectors and dealers seem to put much greater emphasis upon pictorial content and graphic design.

Has the collecting field of ephemera, at the same age, reached maturity? Has it achieved the expectations of its founders and secured a respected and permanent niche in the collecting world?

The veteran dealers and collectors have highly individualized opinions as to what “ephemera” is and ought to be. At least privately, or among themselves, many would probably express a degree of pessimism about the future of the field, bemoaning the fact that the quality of materiel offered and available for sale has gradually declined while prices have skyrocketed. “I rarely find the good stuff anymore, and when I do, I can’t afford it.”

Most general visitors, on the other hand, would not even understand the question. To them, ephemera remains a phrase of uncertain definition, and they don’t think of it as a formal “collecting field” at all.

First-time visitors and new collectors would likely be as wide-eyed and astonished at what is spread out in the dealer booths as those who attended the first Ephemera Show. They would be equally amazed at the dealers and collectors-all these seemingly normal people, obsessed with the most trivial, impractical, but fascinating bits of paper as if they were communion tokens of a new religion. These first time visitors would respond to questions with something like “I can’t believe people collect all this stuff,” while somewhat sheepishly clutching little bags containing the Marilyn Monroe calendar, the four postcards of their unexceptional hometown in Wisconsin, and a trade card of the 1880s showing Jumbo being dragged through the streets of Manhattan by giant spools of Willimantic thread. They paid more than $100 for these treasures and even a week later they would be incapable of explaining why.

Throughout the showroom, visitors are constantly bending the ear of anyone who will listen about how “my grandmother’s house was full of this kind of thing” or “I had every one of those comic books when I was a kid,” until “Mother” or some other thoughtless relative threw them out. This narrative is continually interrupted by fast-moving visitors to each booth who quickly ask the proprietors whether they have any “paper” relating to padlocks, women lacrosse teams, or photographs of dead infants.

Since the health and well-being of “ephemera” is essentially a matter of personal opinion, the writer of this article, a longtime enthusiast, will hazard a few observations of his own-doing so without the least expectation that his opinions are shared by anyone else, or that they are correct!

Thirty or 40 years ago, most of what we prize as ephemera today was the chaff of the antique and book trades-bits and pieces which dealers relegated to boxes in out-of-the-way corners of their shops and marketed at giveaway prices. “Fifty cents apiece, or take the whole box for five bucks.”

The stores I frequented in the 1950s sold daguerreotypes from a cardboard carton for 50 cents apiece, sheet music volumes full of lithographic covers, or scrapbooks of trade cards for $5 of $10 each, stereo cards or 78 rpm records of Caruso or Bessie Smith for a nickel. You did not endear yourself to, or get any medals for brilliance from, either mother or spouse if you bought this “old junk” into the house. When a grandparent or great aunt died and the family homestead was emptied, “old stuff” of any sort was generally thrown out.

Fortunately, there had been a few foresighted collectors who valued what others did not. In the field that we now call ephemera, Bella Landauer was the most brilliant pioneer, collecting trade cards, sheet music, engraved letterheads, and all manner of such things in the first decades of the 20th century. She shared her vision with the public in a series of publications, and these illustrated books and booklets, as well as her lifetime collections at the New-York Historical Society, helped to inspire a new generation of enthusiasts.

Simultaneously, Harry Peters became intoxicated with what he called the “vast and absorbing jungle” of 19th-century lithographs. Describing the field as “the greatest existing area of Americana yet unexplored,” he published four remarkable guides between 1929 and 1935, literally establishing a market in lithographs of Currier & Ives and other contemporary engravers and giving the material a degree of academic respectability it had never enjoyed previously.

Harry Dichter, almost penniless himself, spent a lifetime accumulating old sheet music, and his catalogs of the 1940s and 1950s identified prize items and helped establish a sense of relative values. These were a handful of other such pioneers.

Some types of ephemera, such as bookplates, political buttons, paper currency, postage stamps, valentines, and early printed broadsides have been prized for years. Stamps in particular developed specialized journals and collecting guides, clubs, and “a trade” well before the end of the 19th century. In many ways, stamps set a pattern for the development of any specialized field of collecting.

Baseball cards and comic books begin a transformation from collections of “kid things” to well-defined adult investment hobbies in the 1960s. Early photographs and picture postcards showed signs of becoming serious specialties by the 1960s and have gone wild since. Stereo cards have become a specialty with their own exclusive shows.

But as late as 1980, there was no obvious home for collectors of such disparate materials as letterheads, theatrical programs, posters, menus, trade cards, invitations, rewards of merit, trade catalogs, timetables, die cuts, matchbooks, and labels. Neither book nor antique dealers made this sort of thing a priority. Auction houses only sold the stuff as undescribed bulk lots, if at all.

It was to fill this gap, to provide a congenial meeting place where collectors of such items could meet, buy and sell, and share information, that the Ephemera Society was founded. Most of the “dealers” in ephemera were themselves, collectors. Even today, there are very few full-time ephemera dealers. Some of them spend most of their time selling books or antiques. Many have full-time regular jobs having nothing to do with “the trade.” Overall, this is probably a very healthy thing for the field. The “dealers” have much in common with their customers, and they retain the sort of collectors’ enthusiasm which is easily lost if it all becomes merely a business.

The field of ephemera has, unquestionably, developed a degree of maturity since 1980 as a result of the founding of the Ephemera Society and the shows which it sponsors. How much progress has been made? In what ways? How does the future look? Specific answers are difficult to provide, because “ephemera” is not a specific “thing” but an umbrella encompassing many specialties. The sub-fields show various levels of development, making it hard to generalize.

There exists a sort of evolutionary progression in collecting. The first, or pioneering phase, involves an awakening of interest and appreciation on the part of a few foresighted collectors and dealers that there is a legitimate and exciting area of research and collecting among objects previously given little attention. The second, or accumulative phase, involves isolating, seeing, and acquiring as many examples and varieties as possible-assembling and studying enough information about vast quantities of individual pieces so as to begin understanding developmental patterns of production and design.

The third might be called the bibliographical phase. It involves creating specialized catalogs, lists, price guides, and descriptive literature. This generally encourages a new generation of collectors to enter the field and helps to establish a relative sense of monetary values.

The fourth phase involves academic credibility-achieved by exposure and acceptance, through serious, comprehensive descriptive publications, of previously ignored material objects as legitimate documents and records of social history and artistic endeavor.

Colonial American furniture and decorative arts, American folk art, jazz recording, and film are all object-oriented aspects of American social history which have progressed through each one of these phases in the 20th century, from remarkable, widespread public ignorance to complete academic respectability. The objects on which they are based, many of them considered unworthy of institutional consideration not long ago, are now avidly collected and highly prized by museums and university libraries. It was largely individual collectors and enthusiasts, not institutions, who discovered and established the fields, and yet, ironically, one of the results of success has been to eliminate the average collector from the market for the finest objects themselves.

How far along has this progression occurred in the field of ephemera? Is there a danger that the entire collecting market will succumb to its own triumphs in the years to come? The answer is both yes and no. To some extent for the field as a whole and for some of the specialties falling under the broad ephemera umbrella, the years between 1980 and 1998 have witnessed a coming of age.

Publication has played a notable role in advancing the field. Whereas 20 years ago, there were very few general collecting guides, price lists, or detailed studies of ephemera and its specialties, there is now a sizeable literature. The Ephemera Society, itself, by its newsletters, its journal, and its conferences, has educated not only the average collector but the well-heeled investor and institutional collector.

General antique and book dealers, who were a major source for early collectors, have begun selling ephemera themselves. Why let a middleman reap the largest profit? Even the major auction houses have begun selling posters, trade cards, postcards, comic books, children’s literature, illustrator art, and “historical” photography, establishing price records that amaze veteran collectors. Major libraries and museums have become serious ephemera collectors, accepting major gifts of private collections that permanently removes some of the finest material from the market. Extremely fine and important lithographs, original advertising art, early posters, printed broadsides, and photographic items, yet available at fairly reasonable prices in 1980, have become truly scarce and extremely expensive.

But the effect on the field as a whole is minimized to a considerable extent. For one thing, the founders of ephemera as a separate collecting field set their goals modestly and with common sense. Chippendale furniture, Copley paintings, and George Washington letters never were part of the original idea. The emphasis, from the very beginning, was on the art and the everyday objects of the average men and women of the past. Much of it was either crude in design or was mass-produced, and there is a limit as to how scarce or how desirable much of it will ever be to institutions or investors.

Of course, a few of the very best and rarest pieces will disappear from the market, but new collector interests are constantly developing and new ephemera is constantly being made. Twenty years ago, dealers could hardly give away single issues of newspapers or magazines. Now they have become highly prized, and there is virtually an inexhaustible supply. In our materialistic, throw-away world, the free enterprise system continues to generate the same excitement and nostalgia that older stuff does for our generation. We older generations, of course, help the process of future scarcity along by obliviously throwing out this modern “junk” just as our mothers did our baseball cards and Superman comics!

The irony of it all is that the imprecision of the field of ephemera and the inability or unwillingness of the Ephemera Society to rigorously define itself and restrict its shows to only “museum quality” materials turns out to be one of its greatest strengths. The leading antique and art shows wage constant battles to restrict exhibitors and the types of material they can sell. They have intentionally catered to snob appeal, to exclusivity, and in the process, they have lost the new and average collector to flea markets.

The Ephemera Society, and the show it sponsors have also attempted to admit only responsible, honest exhibitors, but they have never imposed rigorous standards with regard to what may and may not be exhibited. How could they, when no one quite knows how to define the field itself? This has annoyed certain members, but the result is that ephemera remains a delightful “free form” of collecting, where the variety of material offered for sale is almost boundless and prices of much of it within the reach of the most impecunious novice collector.

Ephemera will continue to change, as a field, from year to year, and that is what will keep the field among the most exciting in the collecting world. Ephemera is a truly democratic hobby, not only in subject matter, but in its public appeal, pricing, and collector base. Unless someone messes it up in middle age, ephemera promises to have a very long and very healthy existence for many years to come.

“By the way, do you have any mattress labels (you know, those ones that say it is illegal to remove) the Publisher’s Clearing House brochure for 1993, or tickets for any of the Beach Boys revival tour concerts?”