Publishing the Railroad Ephemera

Publishing the Railroad: The Ephemera Bonanza

By Carlos A. Schwantes

History Professor Emeritus, University of Missouri – St. Louis

Several years ago, I reviewed a book, massive in size and gorgeous in appearance, by Ian Kennedy and Julian Treuherz titled The Railway: Art in the Age of Steam. I subsequently visited the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City to savor for myself the large exhibit upon which their book was based. I doubt that a better collection of fine art devoted to the railroad has ever been assembled or so beautifully displayed—or ever will be again. I realized, however, that railroads around the world were responsible also for a remarkable outpouring of illustrations that even if they did not rise to the level of “fine art,” nonetheless spoke to the industry’s need to visually captivate an audience. I offer here a tiny sample of such illustrations I’ve acquired over a lifetime. Collectively, these ephemera images showcase the rich visual legacy that resulted from the railroads’ role in inventing modern time and space. Their publishing activity thus documents the numerous ways in which they literally reshaped the world (1).

The railroads of North American generated many different types of paper documents—from passenger tickets and wall calendars to train orders and bills of lading. In this space, I want to showcase the type of ephemera that railroads most clearly intended for public consumption, and thus these images speak to the railroad industry’s investment in the incredible variety of eye-catching illustrations used to enliven visually their timetables and promotional brochures. At first, however, neither type of publication was very attractive. Only during the final decades of the 19th Century did publications intended for public consumption evolve visually from the drab black-and-white broadsides and text-only advertisements that railroads placed in newspapers to communicate their train times to the traveling public from the 1830s through the 1850s into the riotous color illustrations used on the covers of public timetables and the thousands of different brochures that the North American railroad industry once issued to promote vacation destinations as well as to entice settlers to create farms, ranches, and towns along their newly laid tracks.

(1) Ian Kennedy and Julian Treuhertz, The Railway: Art in the Age of Steam (New Haven: Yale University Press, [2008]).

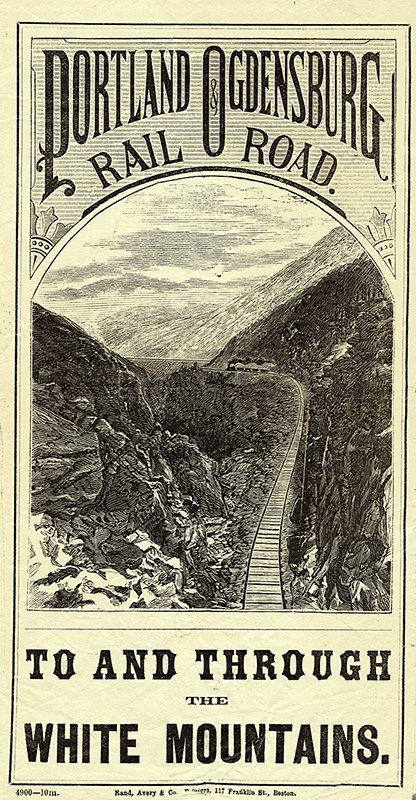

Figure 1

This timetable cover from 1877 represented a great improvement over the visually uninteresting announcements that railroads inserted in local newspapers during the years from 1830 through 1865 to inform travelers of their train arrival and departure times.

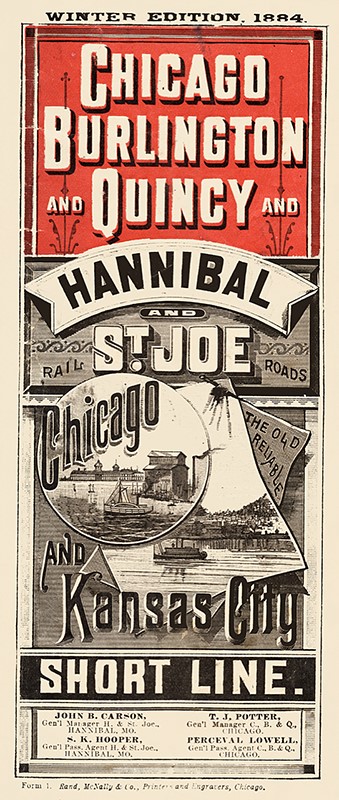

Figure 2

During the 1880s and 1890s, railroads introduced color graphics to add visual interest to their public timetables. A station display might feature public timetables from several dozen different railroads, all of them competing for the viewer’s attention. The Hannibal and St. Joseph was Missouri’s most successful railroad in the 1880s, but as this timetable cover indicated, by that decade it had clearly gravitated to the Illinois-based Chicago, Burlington & Quincy to further the bitter railroad rivalry between Chicago and Saint Louis.

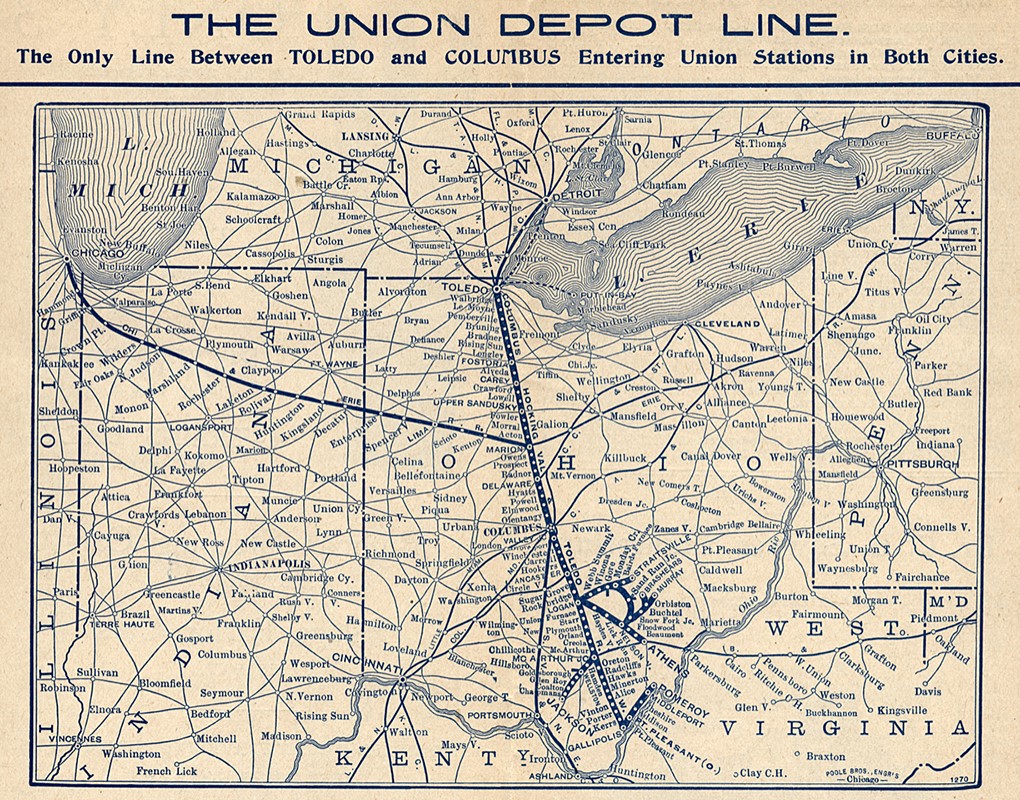

Figure 3

A railroad’s public timetable invariably included a system map designed to create the illusion that the route was as straight as possible. This one shows Hocking Valley tracks making a beeline across central Ohio in 1899.

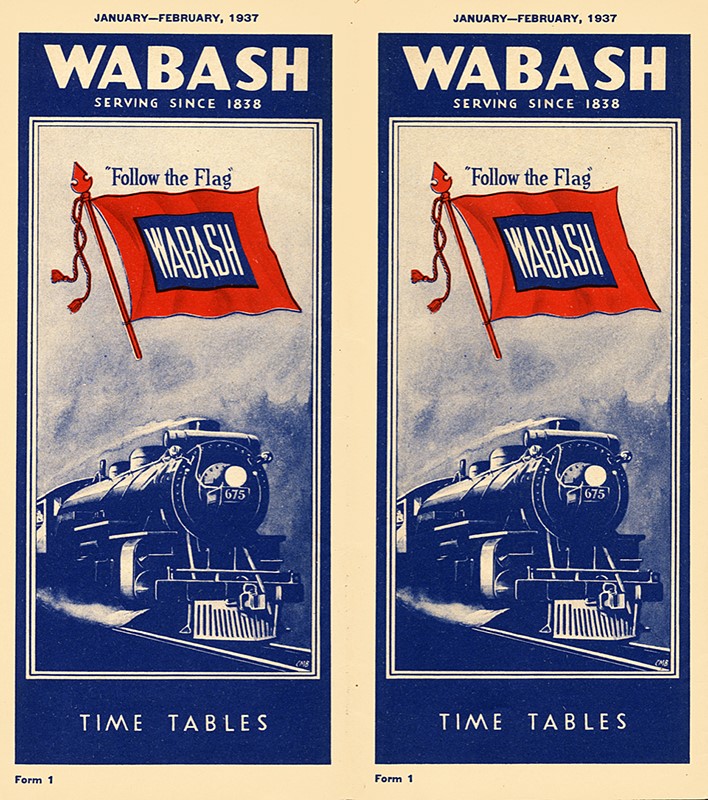

Figure 4

The eye-catching cover of a Wabash public timetable from 1937 showcased the railroad’s powerful passenger locomotives, a graphic symbol of speedy and efficient transportation.

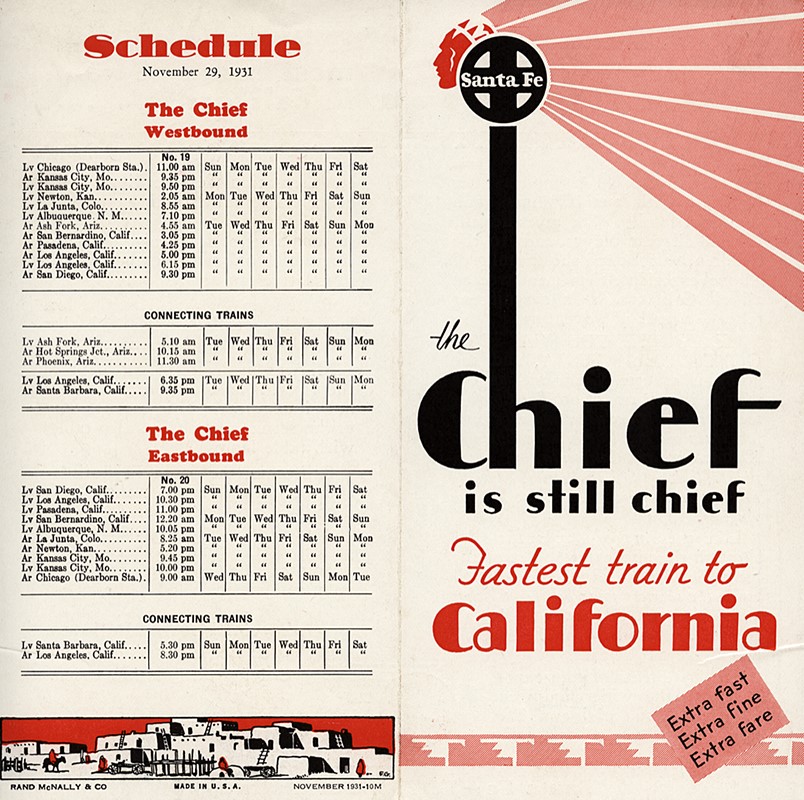

Figure 5

Railroads regularly issued brochures designed to showcase their premier passenger trains. The Santa Fe used the popular Art Deco style of the 1930s to call public attention to its Chicago-Los Angeles streamliner, “The Chief.”

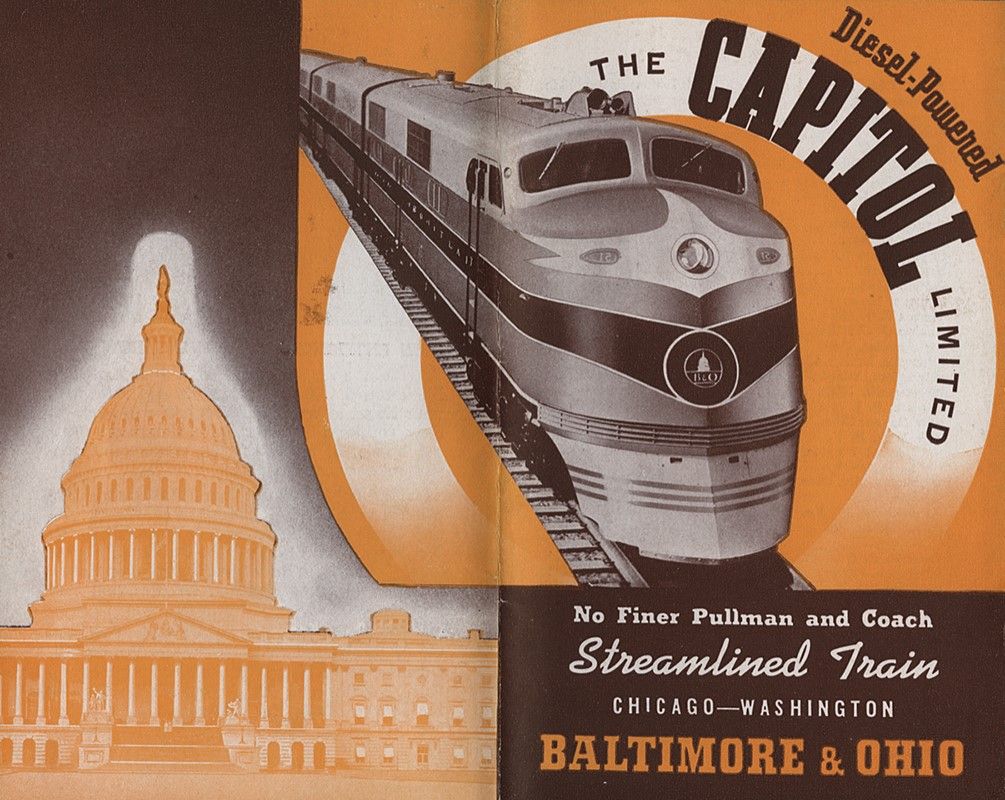

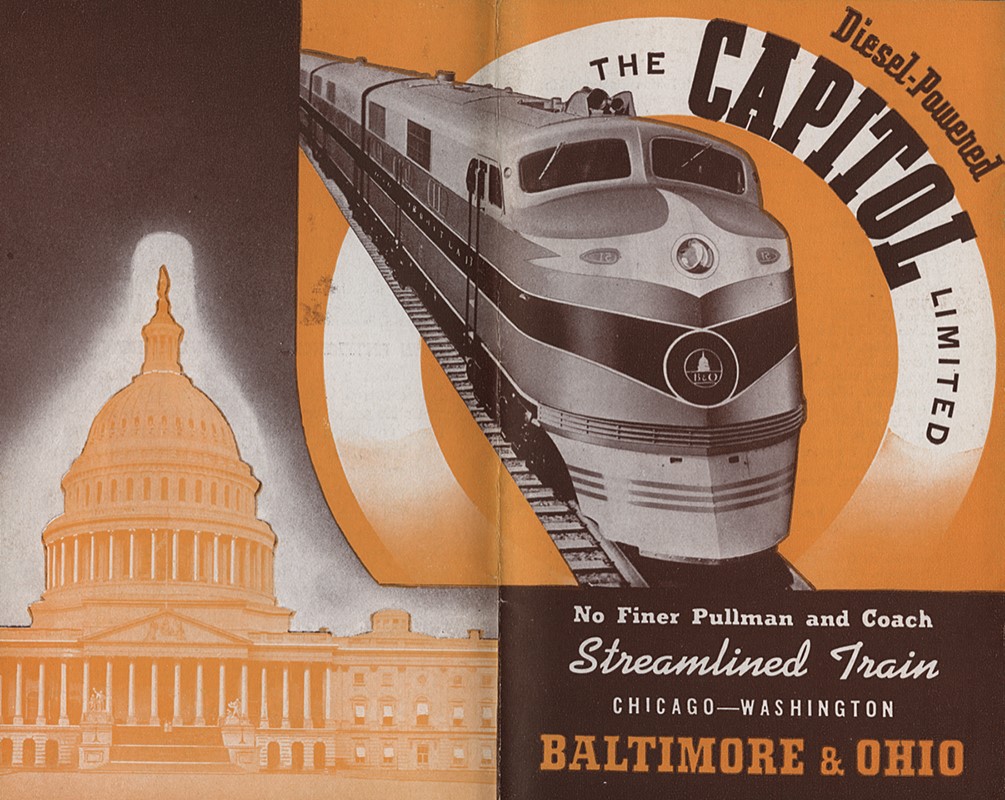

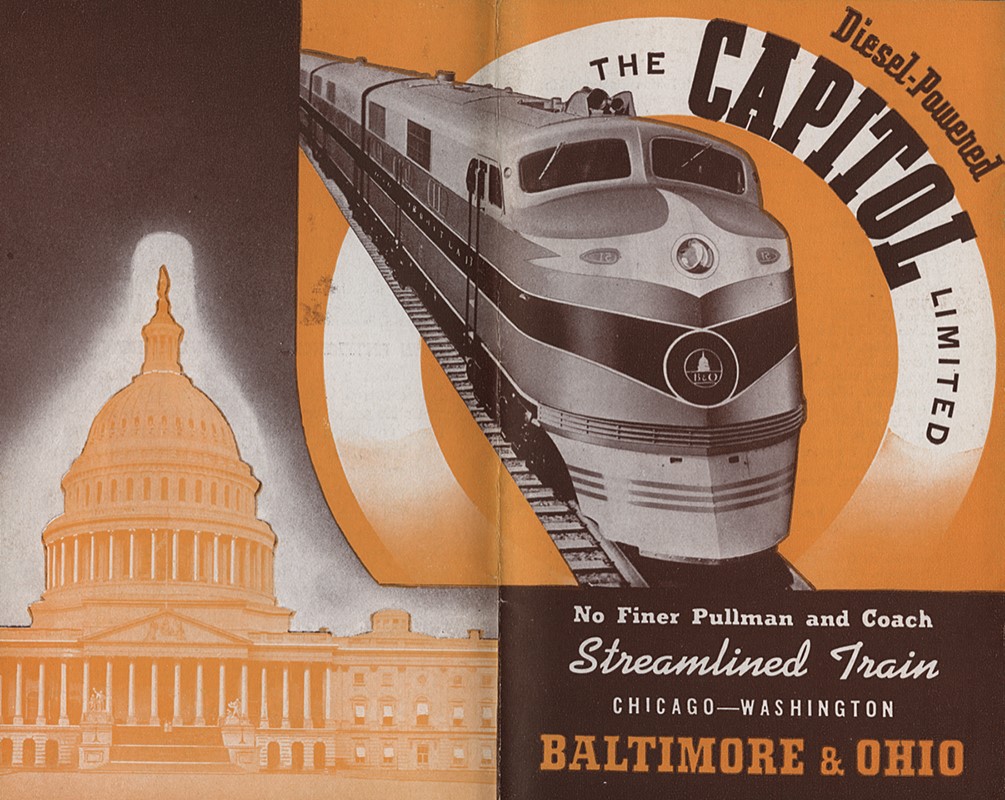

Figure 6

This Baltimore and Ohio brochure from the late 1930s or early 1940s saluted “The Capitol Limited,” its premier Washington-Chicago streamliner as powered by one of General Motors latest Diesel locomotives. At this time, railroads across the United States had begun the process of switching from steam to Diesel power, a monumental transition they completed during the 1950s.

Figure 7

Railroads regularly issued brochures for all kinds of special occasions. The Cotton Belt, a Saint Louis-based railroad, saluted the return of Confederate battle flags in 1905.

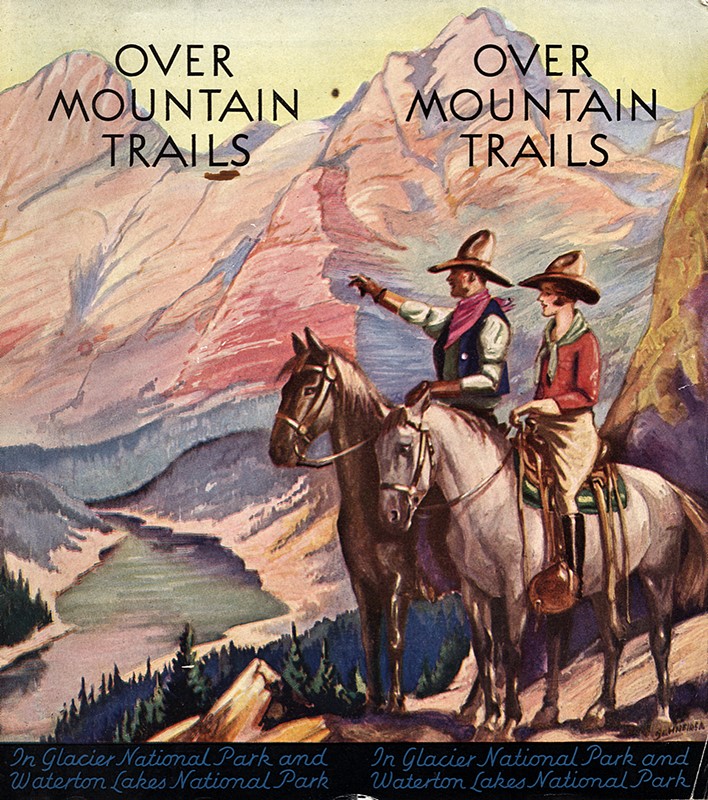

Figure 8

The Great Northern was one of several western railroads that annually issued vacation promotional brochures. This 1920s brochure highlights the appeal of Montana’s Glacier National Park, the southern boundary of which abutted the railroad’s right-of-way. No states generated a greater variety of railroad promotional ephemera than California and Colorado.

Figure 9

Railroads of the East also promoted vacation attractions. A New Haven brochure from 1931 highlighted the possibilities of southern New England where it was the dominant railroad.

Figure 10

Electric interurban railroads, though they typically served a limited geographic area, emulated their big-league steam railroad cousins by publishing a variety of attractive promotional brochures. This cover image appeared on a brochure issued in the late 1920s or early 1920s to highlight the Rochester area served by New York State Railways.