How to Date Cards

When people think about Ephemera, they typically think of paper – paper to which information has been added. Manuscripts are paper to which pencil or ink has been added. Trade cards, newspapers, bill and letterheads, menus and broadsides are paper to which ink has been added. Many, but not all photographs are paper to which a light-sensitive emulsion has been added.

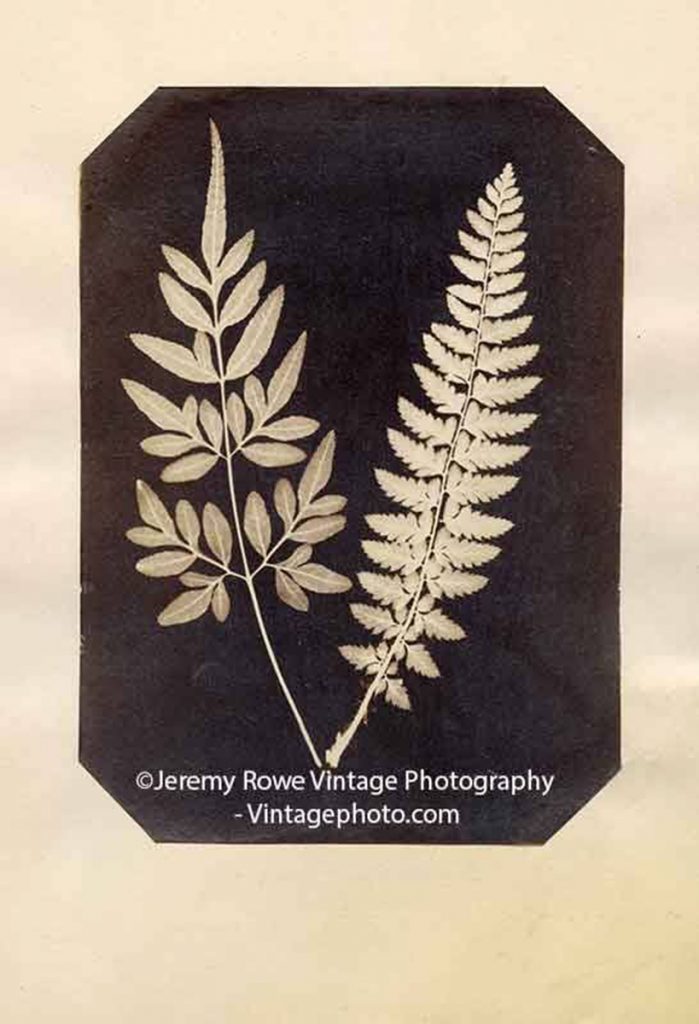

Salt print of botanical specimens, Photographer unknown, ca 1850

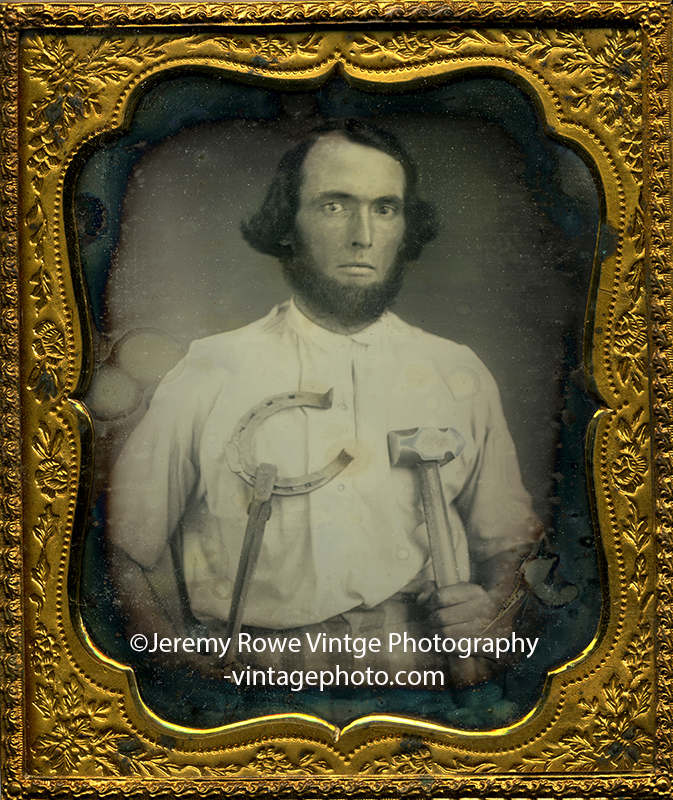

Photographs are clearly recognized as Ephemera. Though in numbers, most photographs consist of paper and emulsion, popular photography began with images on silver-coated copper plates – the Daguerreotype – that was publically announced in 1839. Other non-paper processes were popular during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The ambrotype – a collodion photographic emulsion on glass – gained popularity in the mid-1850s, as did a less costly variant on japanned metal – the ferrotype or tintype.

Sixth plate Daguerreotype of blacksmith Photographer and location unknown, ca 1855

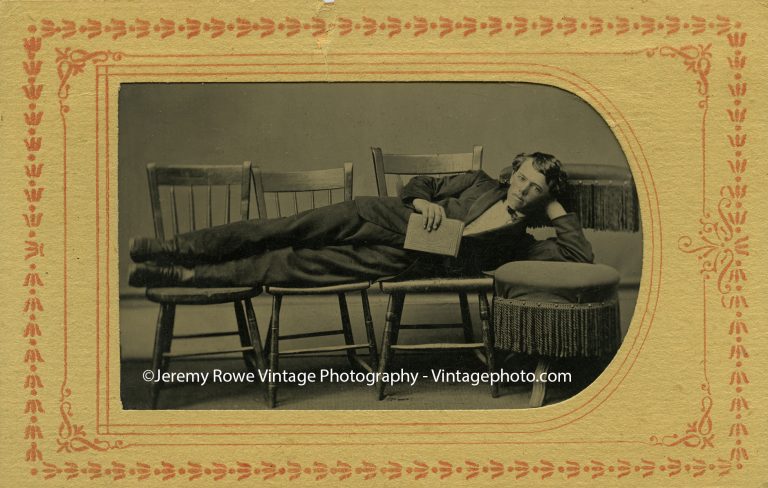

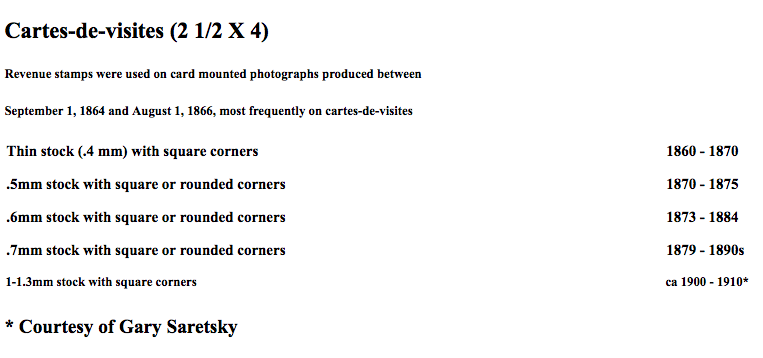

Although alternative paper-based photographic processes, including salted paper and calotypes, paralleled the Daguerreotype, paper photographs didn’t begin to rival the popularity of other processes in popularity into the mid-1850s with the introduction of the collodion wet plate negative and albumen printing processes. Initial popularity of the 2 ½” X 4” (6.35 X 10.16cm) cartes-de-visite (CDV), or visiting card photo, and later the 4” X6 ½” (10.16 X 16.5 cm) cabinet card, along with larger format images became the formats of choice for photographers, who produced millions of paper images as the popularity of the daguerreotype and ambrotype waned. However, the tintype continued its popularity into the 20th century, largely due to its low cost and convenience.

Sixth plate Daguerreotype of blacksmith Photographer and location unknown, ca 1855

Researchers interested in unraveling the information about a given photograph can take advantage of a number of embedded clues.

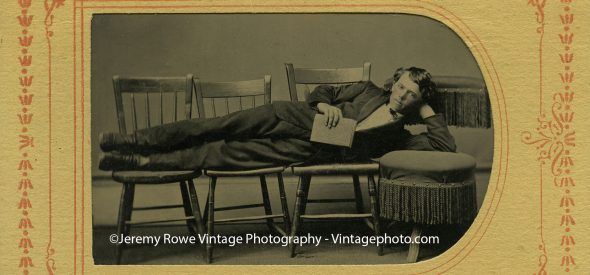

Specific photographic formats were popular during relatively limited periods of time and elements that changed can help date an image. The style of mat and case of the Daguerreotype, ambrotype and early tintypes offer clues. Occasionally written material or handwritten notes can be found in the case behind the image.

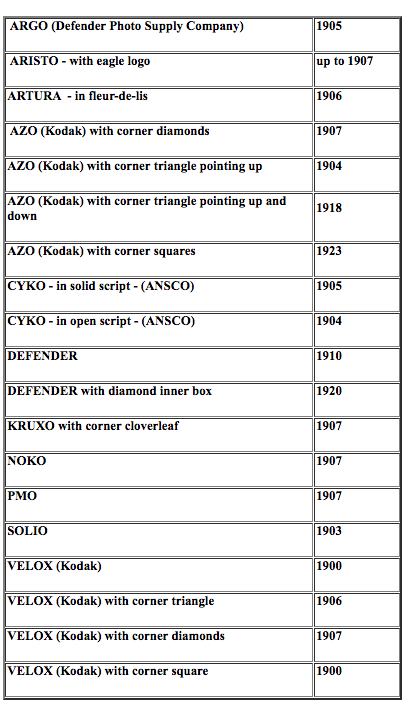

Cartes-de-Visite sized tintype of reclining photographer’s assistant Photographer and location unknown, ca 1880

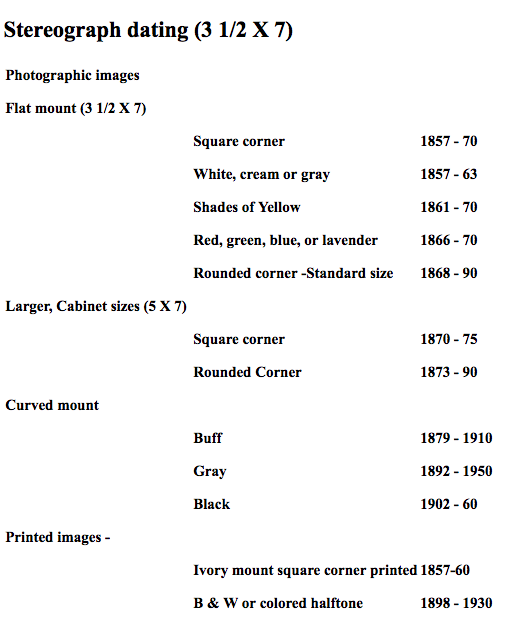

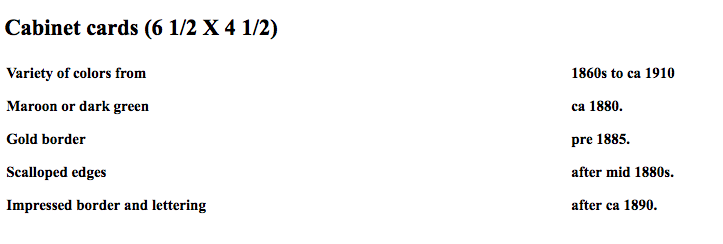

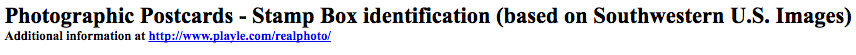

Card mounted photographs from the 19th and early 20th century, such as cartes-de-visites, cabinet cards and stereographs can be generally dated by their format and mount type. Printed mount notations such as photographer’s identification and title are fairly reliable, but can still provide false information.

Cartes-de-Visite of young woman with fan Photographer and location unknown, ca 1865

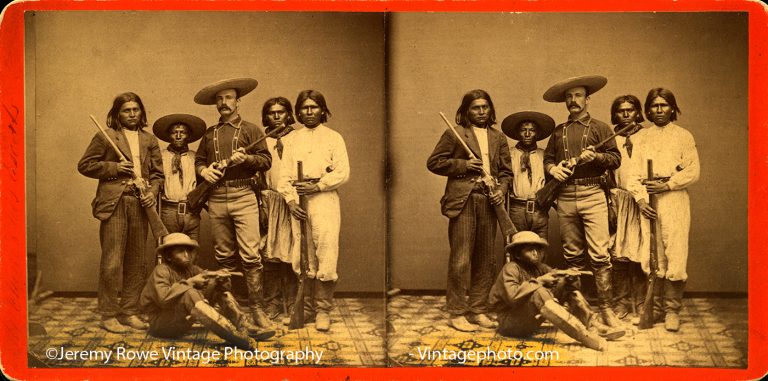

Dating by mount type and style provides a rough indicator for identifying images. The caveat is that many photographers, particularly in more remote areas, failed to keep up to photographic fashion and used old mounts until their stocks were exhausted. Also, photographers reprinted historically or commercially important images long after they were originally taken. Also, negatives were often sold or copied and the mount information may not accurately reflect the history of the images. For example, D. P. Flanders’s views of Prescott, Arizona Territory taken in the Spring of 1874 appear on Williscraft mounts in the late 1870s, and Continent mounts into the mid-1880s.

Stereograph of Apache Agent John Clum and Apache Scouts at the San Carlos Reservation, Arizona Territory Dudley P. Flanders photographer, ca 1874

Notations on the mounts can occasionally provide additional information about the image, but should always be verified by other sources before being relied upon. Handwritten notations are the most suspect, often being added long after the image was made by persons with only secondary knowledge.

Cabinet card of young mother and child Erwin Baer photographer, Prescott, Arizona Territory, ca 1900

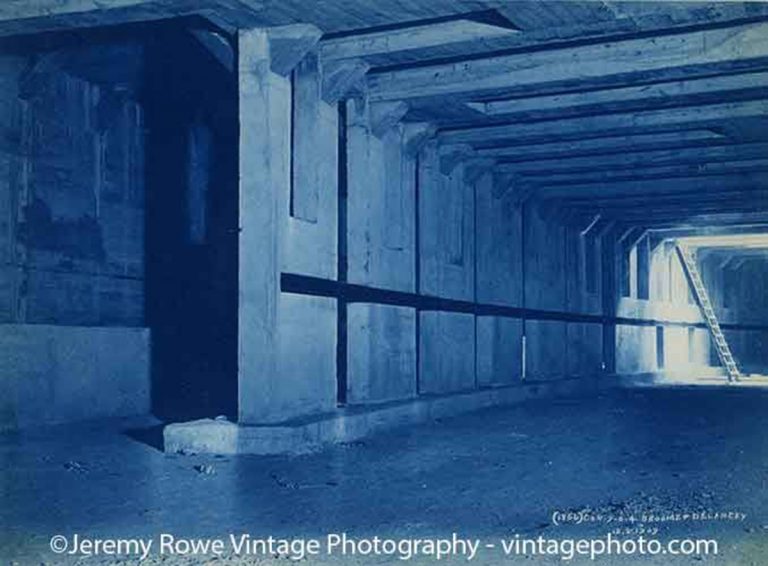

Cyanotype (blueprint) of Broome and Delancey Street Subway construction Photographer unknown, New York City can 1909

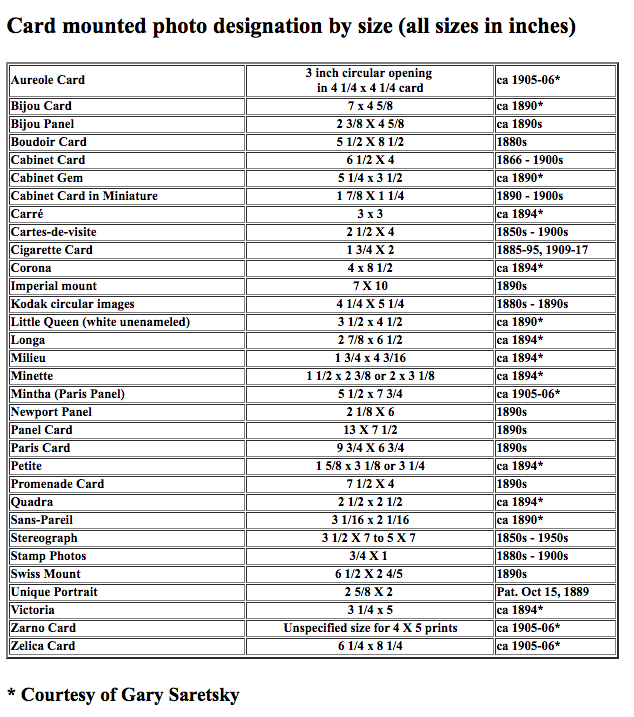

Guide for Dating Card Mounted Photographs

About the Author

Dr. Jeremy Rowe is currently a Senior Research Scientist at New York University. He has collected, researched, and written about 19th and early 20th century photographs for over twenty-five years. He has written Arizona Photographers 1850 – 1920: A History and Directory, Arizona Real Photo Postcards: A History and Portfolio, Early Maricopa County 1871-1920, and Arizona Stereographs 1865 – 1930, as well as numerous chapters and articles on photographic history.

He has curated exhibitions with many regional museums, Sky Harbor Airport and a permanent exhibit at the Talking Stick Resort in Scottsdale. Jeremy serves on several boards, including the Daguerreian Society as President, The Ephemera Society of America, INFOCUS – the Phoenix Art museum Center for Creative Photography collaboration, Daniel Nagrin Theatre Film & Dance Foundation Inc. as Chairman of the Board, and National Stereoscopic Association.

Jeremy served as Arizona coordinator for the Library of Congress American Memory project, a digital historic photographic collection and was a co-principal investigator on other digital library and 3D modeling and visualization projects including a National Science Foundation-funded 3D Digital library project, Knowledge and Distributed Intelligence and projects funded by In-Q-Tel, NEH, NEA, IMLS, DOD and NOAA. Jeremy serves as an accreditation Consultant Evaluator for the Higher Learning Commission of the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools, and as a Fulbright Specialist.