From Society Balls to Buffalo Tails, Ephemera Traces Grand Duke’s Tour

“The Russians are coming! The Russians are coming!” could well have been the chant in 1871 as excited Americans prepared for the arrival of the Grand Duke Alexis and his entourage of Russian dignitaries. For the United States, entertaining royalty from abroad was a rare event, but the Duke was on a mission, and citizens would see to it that his tour was the tour of all tours.

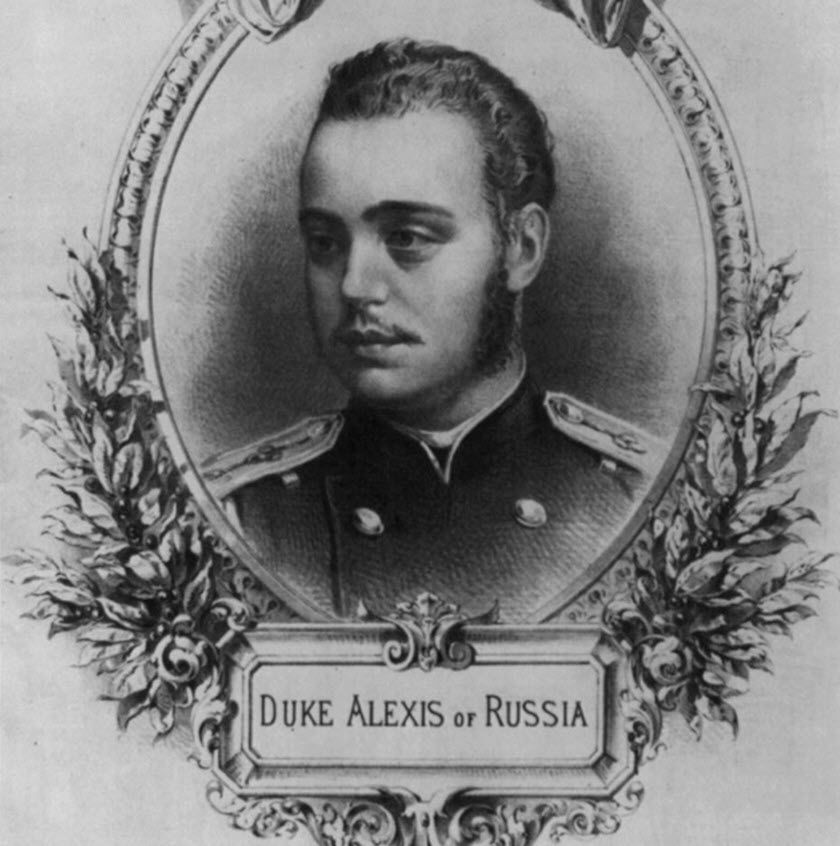

Alexis was a handsome bachelor, just twenty-two, and an officer in the Royal Navy when his father and current Czar, Alexander II, sent him on a goodwill journey to foster an amicable relationship and continuing trade between the two countries. Both nations had a history of scratching each other’s backs.

Russia mediated a settlement between America and Great Britain during the War of 1812.

America showed sympathy for Russia during its Crimean War of the 1850s, which led to increased trade.

Russia backed the Union during our own Civil War in hopes that a strong U. S. would counterbalance the European strength of England and France, both supporting the Confederacy.

The purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867 cemented a bond between the two giants that further insured mutual support.

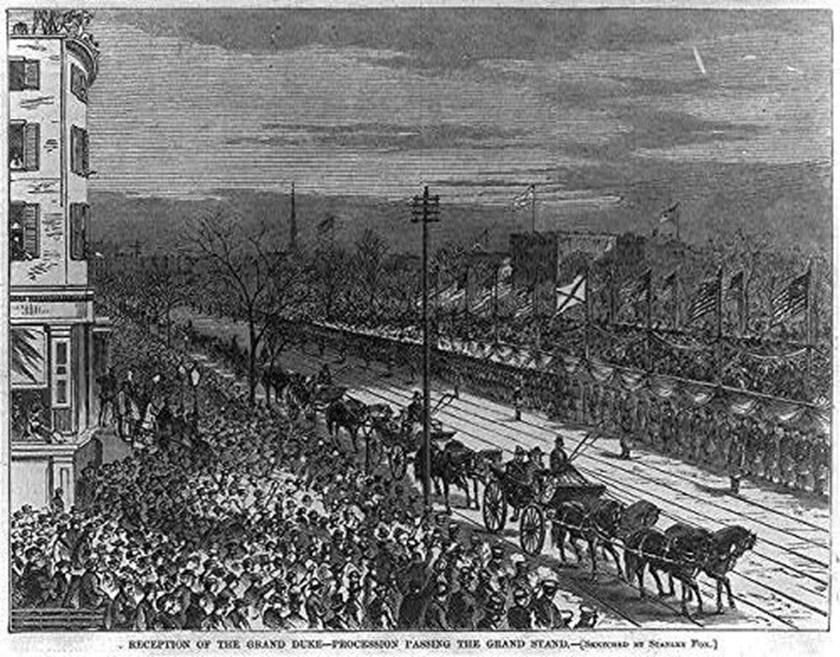

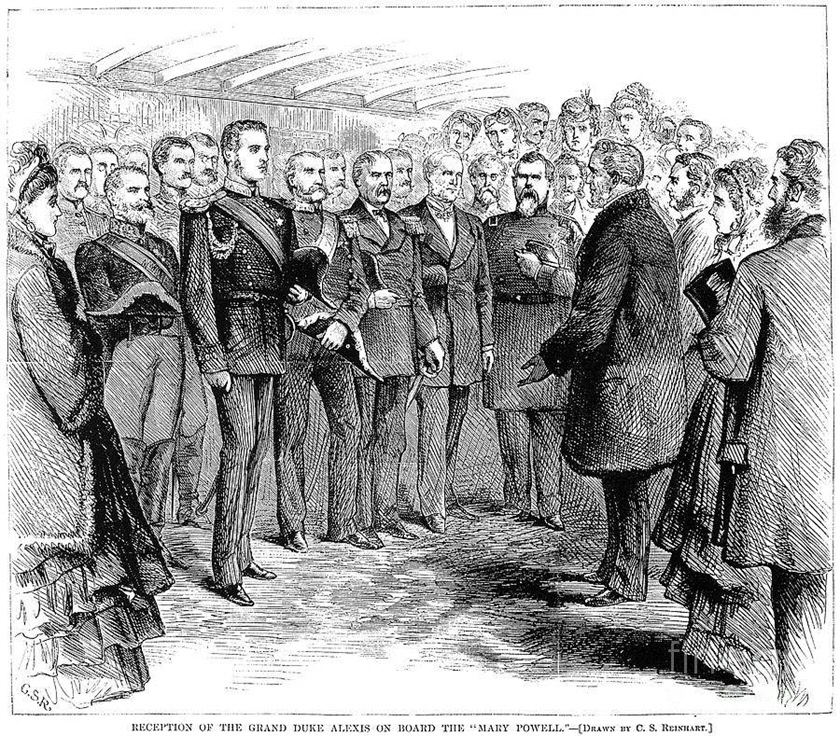

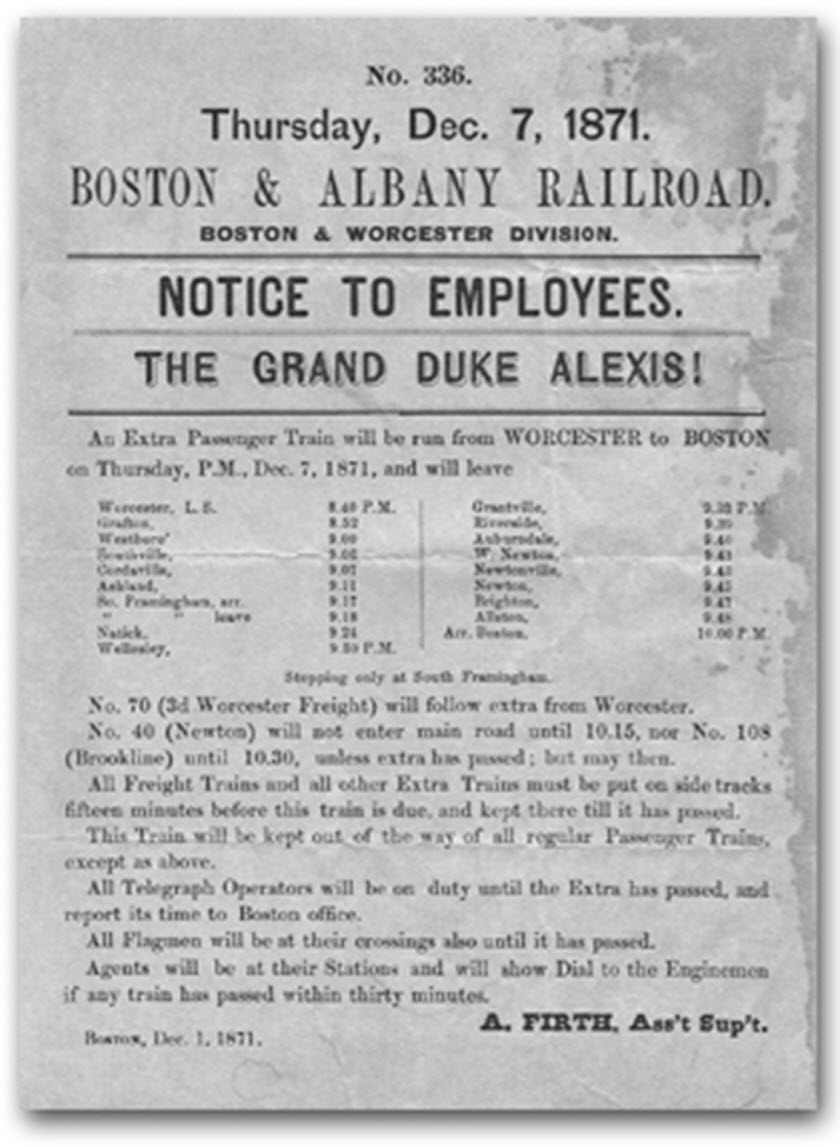

In appreciation, the nation went all out to show Alexis the ultimate in American hospitality. First-class hotels polished their finest suites. Banquet halls were decorated to the hilt, while chefs concocted gourmet feasts fit for royalty. The Pennsylvania Railroad assigned a manager to oversee the train that would transport Alexis in luxuriously outfitted Pullman cars. Local stationmasters along the route were instructed to keep all other trains out of the way of His Imperial Highness.

Between November 1871, and February 1872, the Grand Duke’s travels took him through several eastern states, north to Montreal, as far west as Denver, then through the American South before departing from Pensacola, Florida.

Alexis’s youthfulness undoubtedly helped him survive a whirlwind ordeal of lavish banquets, society balls, parades, and an unending schedule of receptions filled with equally unending speechmaking on the part of his hosts. Crowds – sometimes numbering in the thousands – turned out to greet him at railway stations and hotels. Bands struck up the Russian National Anthem. He exuded a royal presence, spoke fluent English with a heavy Russian accent, and exercised a flair for flirting with the ladies.

When he wasn’t hobnobbing with dignitaries, he toured Philadelphia’s Baldwin Locomotive Works and the Smith and Wesson gun factory in Springfield, CT. Both companies were providing equipment to Russia. In nearby Bridgeport he was treated to a practical demonstration of the celebrated Gatling gun at the Union Metallic Cartridge Company. Alexis reviewed the cadets at West Point and examined rare Russian volumes in the Harvard library. Escorts guided him through steel plants, grain elevators, and carpet mills.

When Alexis arrived in Chicago a couple of months after the city’s devastating fire, the destruction so overwhelmed him that he donated $5,000 to the mayor’s relief fund. He took time out to make the rounds of major photographic studios. In New York, he posed for the cameras of such prominent photographers as Brady and Sarony. They churned out portraits that were snapped up by the throngs who wanted mementos of the Duke’s visit.

In the evenings President Grant and other prominent citizens toasted their royal guests and the future of Russian-American cooperation. When the east coast legs of the tour ended, Alexis eagerly looked forward to the most anticipated event on his schedule – a trip to the Wild West frontier, highlighted by a grand buffalo hunt on the Nebraska plains.

Months in advance of the Duke’s arrival, Albert Bierstadt, the famed landscape artist, was aware of Alexis’s desire to hunt buffalo. Bierstadt was heavily involved in arranging entertainment and returned to the East in September of 1871 from a sketching trip in California to help coordinate plans. He conceived and laid the groundwork for the hunt.

On July 3 he wrote to General William T. Sherman for assistance:

“You are doubtless aware that the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia is to be here in October, and I have learned that he is quite desirous of witnessing a Buffalo Hunt. As his visit partakes of a somewhat national character, would it not be well to give him one on a grand scale, with Indians included, as a rare piece of American hospitality?

If a large body of Indians could be brought together at that time, say the latter part of October, the performance of some of their dances and other ceremonials would be most interesting to our Russian guests. This would probably be the only way to give them a correct idea of Red America. Some of the best Indian hunters might go with the party on the buffalo hunt, to show the aboriginal style of “going for large game.” The herd could be driven up at the proper time within searching distance of the railroad.

It would add very much to the happiness and well being of our guests if you could find time to accompany them in person. In default of that it might accord with your views to delegate some officer of rank, as Sheridan for instance, in your place. This visit of the Grand Duke should be made a matter of no ordinary attention, as it has clearly a more important meaning than the mere pleasure trip of a Prince.”

President Grant ultimately directed Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan, an old hand at staging such events, to take charge of arrangements for the granddaddy of all buffalo hunts. An elegantly designed timetable announced that on January 12, 1872, Alexis’s special train rolled out of Omaha on Union Pacific tracks to McPherson Station, Nebraska. It carried the Ducal Party, Sheridan, and George Armstrong Custer, now engaged as the Duke’s official escort for the remainder of the tour. There they hooked up with their young guide, William F. Cody, already known as “Buffalo Bill,” and with a host of prominent military officers such as generals Ord, Palmer, and Forsyth.

This retinue of about 500 participants incorporating cooks, teamsters, couriers, and two companies of the Second Cavalry and its regimental band, headed immediately across the cold prairie for “Camp Alexis,” already set up 50 miles south on Red Willow Creek. To give the Duke a taste of “Red America,” Cody used all of his influence to induce a friendly chief, Spotted Tail, to bring his best Sioux warriors to the hunt, where they would demonstrate their hunting skills and add color to the event with their native ceremonial customs.

The hunt consumed two full days, January 14 and 15, across the snowy Nebraska landscape. Herds of buffalo roamed within 15 to 20 miles of camp. Custer, Cody, and the entourage worked out a plan for approaching the buffalo and giving Alexis the opportunity to bring down the first kill. The Duke was no greenhorn. He was an expert horseman and quite adventurous; but in the excitement and eagerness of finally riding among a live thundering herd, he neglected to follow all the advice given him by Custer and Cody.

Eventually, after borrowing Cody’s horse and rifle, he managed to drop the first animal and let loose a victorious round of whoops and hollers. Following tradition he sliced off the tail and passed the bloody appendage from man to man. A wagon of champagne and caviar was then brought up from the rear, and the hunters indulged in the first of many toasts. The hunt continued from one herd to the next, and the entire party joined in a “free for all” slaughter. The Duke bagged several buffaloes during the two-day romp.

Back at camp, the hunters feasted on a variety of wild game. Evenings were spent around the campfires offering congratulations and telling Wild West yarns for the benefit of the Duke. Spotted Tail’s band entertained the party with war dances and mock battles late into the night then wrapped up the show by passing the ceremonial peace pipe. Before retiring to their tents, Alexis presented the chief and his warriors with colorful blankets and a huge bag of coins.

Fortunately, several photos were taken at Camp Alexis. A long-known reference to this appeared in an extremely rare book, The Grand Duke Alexis in The United States of America, compiled chiefly from newspaper articles by William Tucker shortly after the tour. The book states:

“When the party were mounted this morning, and the grand cavalcade was ready to move forward, an enterprising photographer, who had arrived in camp, took a picture of it as it stood with the Grand Duke, General Sheridan, and General Custer at the head, followed by the remainder of the Imperial suite, the officers and soldiers, and the great Indian Chief Spotted Tail and his band of experienced warriors.”

The photographer was identified in a contemporaneous report in the Nebraska Intelligencer of January 16, 1872:

“Mr. Eaton, artist, of Omaha, took some views of the camp, the hunting party, the Duke, Spotted Tail, and other groups, and has received Alexis’ order for several hundred copies of each.”

Some of these previously unknown stereoviews by Edric Eaton have now surfaced. They are as rare as stereoviews can be, which is a mystery considering the popularity of Alexis and the clamor for mementos. Perhaps this was not a commercial venture by Eaton, but a commission by Alexis for his personal use. The book further states:

“Before leaving the camp several photographs were taken by the enterprising artist. They will be interesting souvenirs, especially to the Imperial members of the party who participated in the hunting expedition with General Sheridan and His Imperial Highness. One large view was taken of the party as they sat at breakfast. Pictures were also made of the camp itself, and among the others which were taken by request of the Grand Duke were those of Buffalo Bill and General Custer in his buckskin hunting dress.”

Only six views taken at Camp Alexis have been identified, and the total number is probably very small. They are not particularly exciting; one is quite distant and another of Custer and Spotted Tail is rather blurry. No closeup shots of Alexis at the camp have been seen, nor have some of the other scenes described in Tucker’s book. Eaton, unfortunately, did not follow the party to the actual hunting grounds. That setting would have produced some truly spectacular photos of the personalities posed with their trophies. But the handful of stereoviews that exist are a collector’s dream and the only visual record of this famous western event.

After a hair-raising ride back to the railhead on a converted Army wagon, with Cody at the reins, Alexis and his circle continued on to Denver aboard the exquisitely furnished train. Following another round of banquets and appearances, the Grand Duke and Custer stopped in St. Louis to pose for photographs in their buffalo-hunting attire. Afterward, Custer invited Alexis back to his home in Louisville to meet his wife, Elizabeth, and partake of some southern hospitality.

From there they headed south via Mammoth Cave and Memphis, then down the Mississippi aboard the steamboat, James Howard, to New Orleans, where the party made a grand entrance into the city. Mardi Gras was in full swing at the time, and Alexis became its most prominent star. Some believe that the festival’s long-lived mascot, King Rex, was created to honor his participation in the first organized parade in the event’s history.

As for the success of the U. S. excursion, citizens showed His Highness all the warmth they could muster, and Alexis reciprocated. He saw America as best he could from the vantage point of a dignitary being hustled from one stop to the next. The trip to the frontier was undoubtedly the experience of his life. He got prized souvenirs of the hunt. Several buffalo heads, hides, and a batch of bison-tail trophies were sent back to his homeland. On the downside, the press had a field day ridiculing the hunt and the senseless sport of slaughtering the diminishing numbers of buffalo, which were almost extinct a decade later. When Alexis returned to Russia, his father, the Czar, awarded Albert Bierstadt a medal, the Order of Saint Stanislaus, for his role in planning the hunt.

I stumbled across the Grand Duke’s tour several years ago through the purchase of an original letter written by Bierstadt in April 1871. In the brief message, he invited Major General Dix to an “urgent meeting to discuss the best method of entertaining His Imperial Highness, the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia during his visit in this country.” That one acquisition led to an unquenchable search for more information and artifacts related to the tour. Most articles written about Alexis have drawn upon two basic sources – the book of day-by-day events compiled by William Tucker, and an eyewitness account of the buffalo hunt written by James A. Hadley. Collecting ephemera has added new dimensions to these resources.

One purchase of 62 original telegrams received by Frank Thomson, manager of the Grand Duke’s train, reveals the logistics, scheduling, and complexities involved in getting Alexis from place to place.

Ornately designed railroad timetables show the date and time at which the special train would pass through each little town on the way to the next big city. Banquet invitations list the cast of committee members, usually prominent locals, who planned the extravagant balls and dinners. The stereoviews taken at Camp Alexis finally give us a glimpse of the wintry Nebraska setting where the hunt was launched.

Numerous portraits of the handsome Alexis reveal why the ladies were so eager to meet His Highness.

Gathering material about the tour has led to the assimilation of a significant archive of research material, most likely, the only one of its kind. The great thing about pursuing the trail of ephemera for a subject such as this is that you never know what’s going to turn up next.